Bacurau review – way-out western | reviews, news & interviews

Bacurau review – way-out western

Bacurau review – way-out western

Sonia Braga and Udo Kier star in a genre mash-up with lashings of spaghetti sauce

After his two mysterious, tightly-coiled and idiosyncratic first features, Neighbouring Sounds and Aquarius, the masterful Brazilian director Kleber Mendonça Filho lets his hair down with an exhilarating, all-guns-blazing venture into genre.

Bacurau is equal parts spaghetti western, ultra-violent horror and political conspiracy, with a dash of sci-fi for good measure. While paying homage to John Carpenter, Sergio Leone and Eastwood, among others, it also evokes a rich period of Brazil’s own film lore and, as ever with Filho, offers commentary on current political and social turmoil in his country. This may be a cross-over crowd-pleaser, but it also feels like his most Brazilian film yet.

In fact, this time around Filho is co-writing and directing with his production designer from the earlier films, Juliano Dornelles, and it’s reasonable to assume that the partnership informs the new direction.

The pair start slyly, keeping their cards tight to their chest. The handsome widescreen vista introduces the arid Brazilian hinterland known as the sertão. While a caption announces that this is “a few years from now”, the setting is one that has always represented the social divisions in Brazil’s history; the inhabitants of the sertão have invariably been abused, or forgotten altogether by the powers that be.

Bacurau becomes the archetypal western village that must protect itself from malevolent outsiders

A young woman, Teresa (Bárbara Colen) returns to her home village of Bacurau for the funeral of her grandmother. It feels like she’s entering a place in the early stages of siege. On the way in, a truck has spilled a number of empty coffins into the road, its driver dead beside them. The nearby dam has been blocked, leaving Bacurau dangerously short of water. Bandits are operating in the hills, whose murderous, anti-Establishment raids are watched by the villagers on social media. Theresa herself is delivering much-needed medical supplies.

Despite the problems, the tone in these early scenes is infused with the musical, amiable spirit one associates with Brazil. Even when the corrupt mayor, Tony Junior, clearly responsible for blocking the dam, brazenly arrives in town to canvas votes for the upcoming election, there’s a comic air to the way the villagers treat him.

But this will be much more than a genial and eccentric tale of a backwater town battling against corruption. Filho likes to operate on a slow-burn fuse, and the underlying tension here ever so slowly heats up. Bacurau suddenly disappears from the satellite map, at the same time as the wireless signal vanishes; a drone, with the amusing appearance of a flying saucer, starts following people; a truck delivering water arrives with gunshot holes; a neighbouring farm’s horses gallop through the streets.

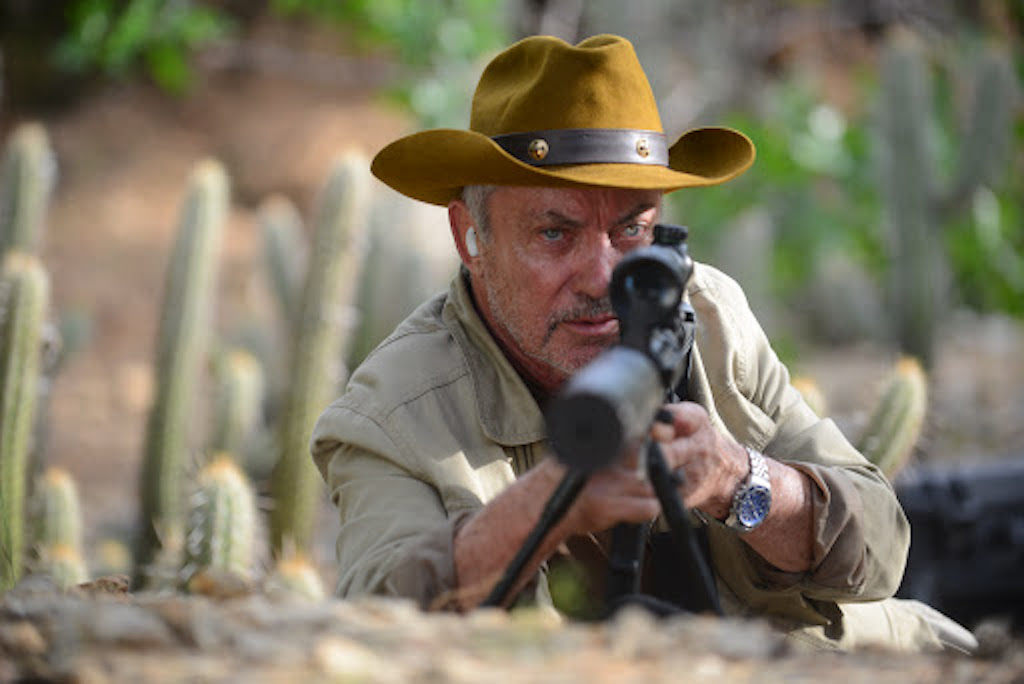

And then two motorcyclists, a man and woman in ridiculously garish gear, ride in and start asking questions. “What are inhabitants of Bacurau called?” asks one, to which a boy answers, “People.” The battle lines are drawn right there, and it’s not long after this that the bodies start piling up and Bacurau becomes the archetypal western village that must protect itself from malevolent outsiders, here a motley group of English-speaking sociopaths who have paid for the privilege of a human safari. What follows is brutal, bloody and often very weird, the latter characteristic rubberstamped by the appearance of Udo Kier (pictured above), whose exotic otherness has graced innumerable B-movies for decades, and here leads the hunt with a particularly nonchalant viciousness.

What follows is brutal, bloody and often very weird, the latter characteristic rubberstamped by the appearance of Udo Kier (pictured above), whose exotic otherness has graced innumerable B-movies for decades, and here leads the hunt with a particularly nonchalant viciousness.

The villains’ sub-Tarantino dialogue and accompanying over-the-top violence account for the film’s least convincing or appealing moments. It comes into its own as the villagers, led by those aforementioned bandits and with the assistance of a large supply of psychotropic drugs, show that they’re not going to just lay down for the westerners. Kier and co really should have done some preliminary research in Bacurau’s history museum.

Indeed, the film is informed by the sense of Brazilian history repeating itself, whether it’s the persecution of the sertão or the current president trying to whitewash the deeds of the country’s former dictatorship. And there’s a nice contemporary reworking of the battles between bandits and landowners in the country’s revolutionary Cinema Novo films of the Sixties and Seventies, when filmmakers were finding inventive ways to comment on that repression.

It’s richly designed and shot, from the funeral procession and other community gatherings to the orchestration of the village for its western climax, with stunning details along the way, not least a child’s bloodstained clothes hanging on a line in the scorching sun. Music adds to the genre twists (notably the use of John Carpenter’s own electronic composition, ‘Night’) as do little touches in the editing, such as the wipes as a form of scene transition, most famously used by George Lucas in Star Wars.

Aside from Kier, the only familiar face in the cast is that of the legendary Sonia Braga, who starred in Aquarius and here offers sometime comic relief as the village’s doctor and combative drunk, who uses first-hand experience in her advice to patients.

“Migraine, nausea, feeling like death,” moans one teenager after the funeral. “That’s a hangover…. Vomit. More water. And vomit again.”

- Bacurau is currently available for streaming on MUBI and Curzon Home Cinema

- Read more film reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Add comment