Remembering Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020) | reviews, news & interviews

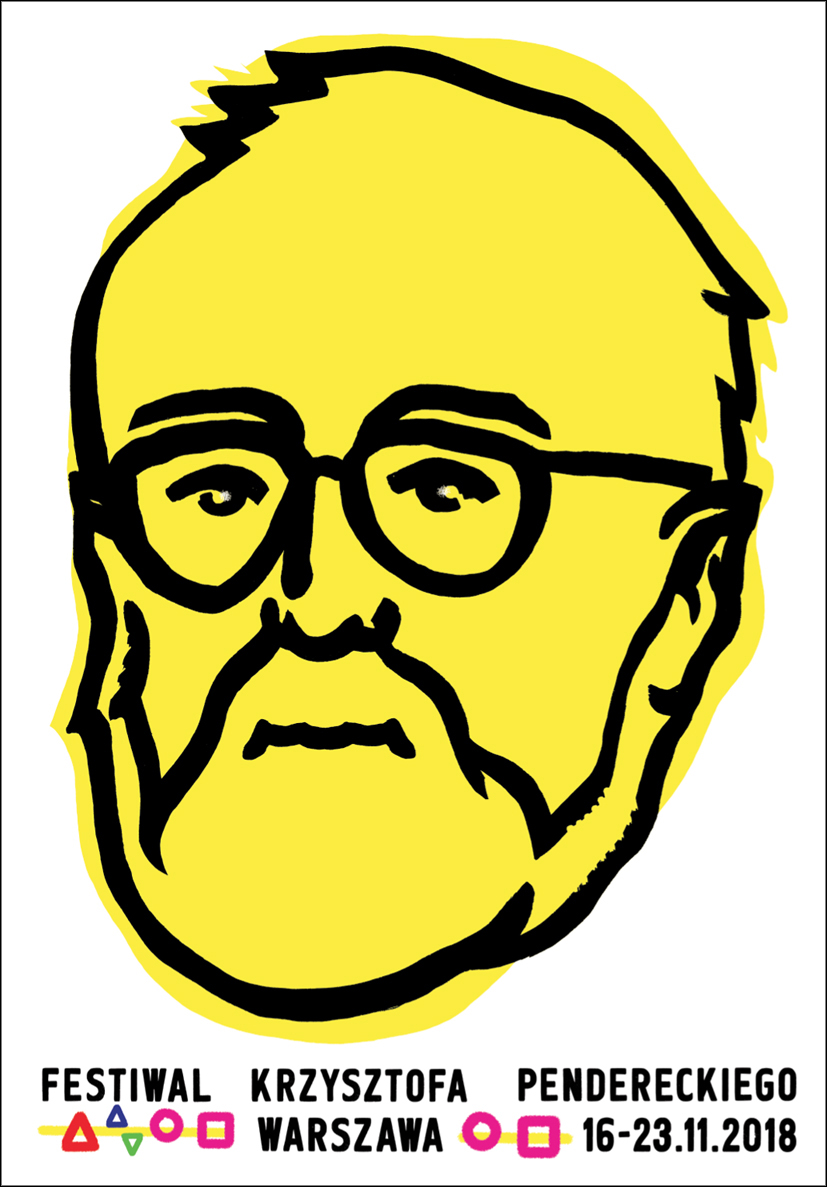

Remembering Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020)

Remembering Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020)

Sixties radical became the spiritual voice of Poland as elder statesman

No composer since Stravinsky has defined his age as comprehensively as Krzysztof Penderecki, who died on Sunday aged 86.

Penderecki’s international career was launched spectacularly in 1959, when he entered three works anonymously for the Warsaw Competition for Young Composers and won the top three places. The pieces, Strophes, Emanations and Psalms of David, were all soon taken up by new music festivals across Europe. The style was modern, but not based on the strict mathematical principles that governed the music of the Darmstadt School in the West. Instead, the music was shaped through a greater focus on instrumental colour, the textures often formed as dense clouds of sound. In 1961, the Polish musicologist Józef Chomiński coined the term “sonorism” to describe the approach, and Penderecki was among its chief proponents, along with fellow Polish luminaries Witold Lutosławski and Henryk Górecki.

Grand musical statements were a hallmark of Penderecki’s composing career, and his early modernism came to a suitably imposing climax with his St Luke Passion, premiered at Münster Cathedral, West Germany in 1966. The piece demonstrated how radical modernist ideas could be integrated into a large-scale form. It also identified Penderecki unambiguously as a Catholic composer – potentially problematic while Poland was still communist, but key to his public profile in the years that followed.

The stylistic path from here to the Romanticism of the 1980s was complex. Penderecki was always massively prolific, and in these years he would often follow different stylistic trends from one work to the next. He began writing operas in the mid-1960s, and The Devils of Loudon, based on the story by Aldous Huxley, premiered in Hamburg in 1969. The macabre story, of demonically possessed nuns and exorcism rituals, inspired a confrontational and Expressionist score from Penderecki. His later operas proved similarly intense, especially The Black Mask, a Salzburg Festival commission from 1986, a claustrophobic tale set during a plague, the music here as terse and complex as anything from the composer’s younger years. On the other hand, his symphonies (eight) and concertos revealed another side to Penderecki, the traditional forms inspiring a conformity, yet without stifling his voice. His Second Symphony has been nicknamed (that itself a rare honour for a modern work) the “Christmas Symphony”, for its repeated, and irony-free, quotations of the carol Silent Night.

Though he continued to write in almost every genre, the last decades of Penderecki’s career were dominated by his large-scale oratorios. Responding to commissions from across Europe, Penderecki created a succession of sacred choral works from the mid-90s onwards, usually premiered as high-profile gala events, with the composer conducting, or else a highly visible guest of honour.

By then, Penderecki had become the elder statesman of Polish music. Through the turbulent years of the 1980s, he managed to remain solidly on the side of the people and against the communist regime. The Polish Requiem secured his status as musical godfather to the Solidarność movement – the work is a setting of the Requiem Mass, dedicated to Lech Wałęsa and written to commemorate those who died in the anti-government riots at the Gdánsk shipyard, as well as the victims of the Warsaw Uprising and of Auschwitz. Like France in the 1970s, when it struggled to lure Boulez back from America, the newly independent Poland seemed at a loss as to how it could honour Penderecki’s already international standing. In the case of Boulez, the French government funded his IRCAM electronic music studio, and the decades of education and research that have since gone on there. Similarly, Penderecki was able to exploit the goodwill of the Polish authorities to found the Krzysztof Penderecki European Centre for Music, a rural retreat hosting education courses and summer schools for young musicians. The Centre was built on Penderecki’s own land, 100 km east of Krakow. The site is also home to his second great passion, his arboretum, the largest in Eastern Europe.

By then, Penderecki had become the elder statesman of Polish music. Through the turbulent years of the 1980s, he managed to remain solidly on the side of the people and against the communist regime. The Polish Requiem secured his status as musical godfather to the Solidarność movement – the work is a setting of the Requiem Mass, dedicated to Lech Wałęsa and written to commemorate those who died in the anti-government riots at the Gdánsk shipyard, as well as the victims of the Warsaw Uprising and of Auschwitz. Like France in the 1970s, when it struggled to lure Boulez back from America, the newly independent Poland seemed at a loss as to how it could honour Penderecki’s already international standing. In the case of Boulez, the French government funded his IRCAM electronic music studio, and the decades of education and research that have since gone on there. Similarly, Penderecki was able to exploit the goodwill of the Polish authorities to found the Krzysztof Penderecki European Centre for Music, a rural retreat hosting education courses and summer schools for young musicians. The Centre was built on Penderecki’s own land, 100 km east of Krakow. The site is also home to his second great passion, his arboretum, the largest in Eastern Europe.

Having represented so many different values and trends in the 20th century, it was probably inevitable that Penderecki would again become a controversial figure in the 21st. His Piano Concerto, “Resurrection,” (2001/2, revised 2007) was retrospectively dedicated to the victims of the World Trade Center attacks, a move many considered exploitative. And Penderecki had form, his Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, one of his breakthrough works of the early 60s, was originally titled after its duration, 8’37”, and only achieved fame after the rebrand. But the dedications acknowledge a fundamental constant in Penderecki’s music – its solemn and often funerial character. That is a property of Polish culture in general, but Penderecki gave it voice, whatever style he happened to be working in. Meanwhile, the controversy around the Piano Concerto, combined with its conservative Romantic style, triggered a new wave of contemporary music in Warsaw, with young composers defining themselves in opposition to everything that Penderecki stood for.

That could well be another service that Penderecki has provided to the new music scene in his country, and even the young composers who opposed his establishment status and conservative style acknowledge the huge influence he has had on Poland’s musical infrastructure. His music lives on, too, in avenues as diverse as the styles in which he worked. Several of his early scores appeared in iconic horror films, and the subtitle of his obituary in this week’s Rolling Stone reads “Conductor’s works featured in The Shining and The Exorcist.” Jonny Greenwood, of Radiohead fame, also holds Penderecki’s early work in high regard, producing an album of remixes, and writing much of his own music in a similar style. Among the concertos of the 80s and 90s, the Horn Concerto, “Winterreise”, has become a favourite with players and audiences, and the Second Violin Concerto, “Metamorphosen”, which was written for Anna-Sophie Mutter, is now a permanent fixture of her high-profile repertoire. And the large-scale choral works will no doubt continue to be performed, especially in Poland. The gala performances will have to do without the composer at the podium, yet the music will retain its significance, a documentary history of the country’s spiritual life in its first decades of post-communist independence.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment