DVD: The Cakemaker | reviews, news & interviews

DVD: The Cakemaker

DVD: The Cakemaker

Israeli debut is a sensitive study of grief - and the joy of culinary creation

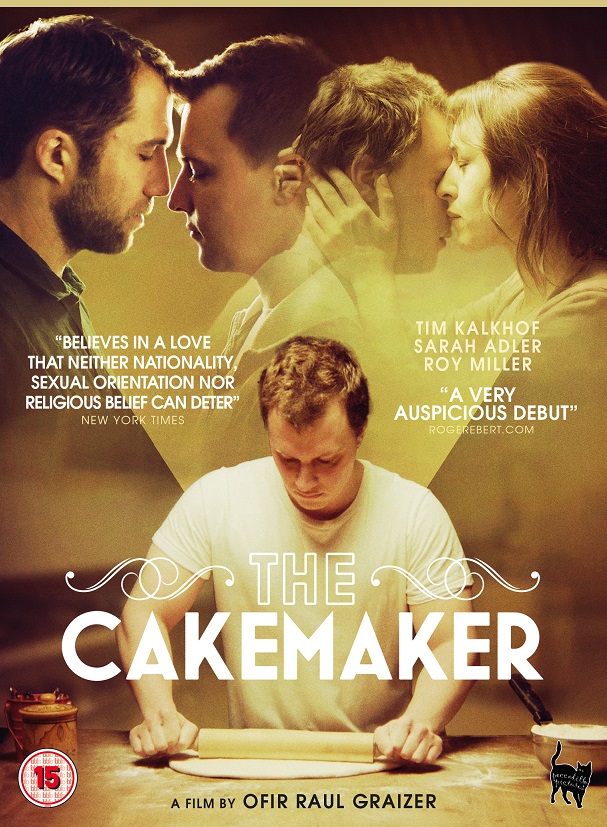

The Cakemaker is Ofir Raul Graizer’s debut feature, and the film must somehow reflect the parabola of the Israeli-born director's life: it’s set between Berlin and Jerusalem, the two cities apparently closest to him, and one of its main subjects – alongside weightier themes such as grief and loss – is

It’s a story of the growth of two relationships, closely interlinked but distinctly separate. It opens in Berlin, where Thomas, a young German baker-pâtissier who runs his own café, encounters Oren, a businessman visiting from Israel; we see almost nothing of the initiation of their relationship, only subsequent glimpses, almost by instalment, that bring home its growing seriousness. Oren is completely open about his having a wife and son back in Jerusalem, his bisexuality a fact that Thomas takes on board as unquestioningly as he acknowledges that their encounters will be restricted to the few days each month when his lover is in Berlin. German actor Tim Kalkhof plays Thomas with few words and a sort of reluctance of self-expression that makes clear that he’s a solitary individual, a loner – one close, too, to loneliness – who accepts this new commitment, however limited, into a rhythm of life that’s intricately involved with his work, especially to the rhythms of kneading dough.

But their relationship is abruptly cut short. We witness Thomas’s anxiety about his lover’s prolonged absence, the telephone calls unanswered, until he eventually learns that Oren has died in a car crash back in Israel – a devastation that, again, is barely verbalised. We are left, equally, rather to guess at Thomas’s exact motivation when he travels to Jerusalem: to familiarise himself with the world in which his dead partner had lived, to observe that from which he had been excluded? Graizer manages the process skilfully, its development natural rather than forced, though he plays on the coincidences of new interaction as we observe Oren’s widow, Anat, trying to rebuild a world for herself and her son. She, too, has a café to run, and when Thomas appears there – concealing, of course, the bond that connects them – it sets in train a process of slow renewal.

But their relationship is abruptly cut short. We witness Thomas’s anxiety about his lover’s prolonged absence, the telephone calls unanswered, until he eventually learns that Oren has died in a car crash back in Israel – a devastation that, again, is barely verbalised. We are left, equally, rather to guess at Thomas’s exact motivation when he travels to Jerusalem: to familiarise himself with the world in which his dead partner had lived, to observe that from which he had been excluded? Graizer manages the process skilfully, its development natural rather than forced, though he plays on the coincidences of new interaction as we observe Oren’s widow, Anat, trying to rebuild a world for herself and her son. She, too, has a café to run, and when Thomas appears there – concealing, of course, the bond that connects them – it sets in train a process of slow renewal.

It’s a story that could very easily approach cliché, an element that The Cakemaker largely avoids, restrained perhaps by the markedly undemonstrative nature of Thomas’s character: he’s only truly engaged, it seems, when he’s cooking, whether that’s cookies or the elaborate Black Forest gateau that is his speciality, however out of place it may seem in this new environment. And the presence of any outsider here is itself complicated, not least in the demands of the café’s kosher certificate that limit the involvement of any non-Jew in the preparation processes. Such details may not be something that Anat herself pays particular attention to, but for others in the family to which Thomas becomes gradually linked they are a subtle indication of difference.

Yet alongside such a relatively naturalistic story development – Jerusalem is depicted in downbeat, everyday detail, unostentatiously relished in Omri Aloni’s cinematography – The Cakemaker also works on a different level, one which has its own distinct logic. It’s there in the lovely strand, tantalisingly brief, that has Thomas meeting Oren’s mother (Sandra Sade, captivating), whose wisdom of age hints that she knows intuitively exactly what has brought him there. And it’s there in the cooking scenes, which become a shared absorption for Thomas and the careworn Anat (Sarah Adler, luminously grounded in her grief). Food in cinema has a well-established magic behind it, the sheer magic of its creation bringing a powerful, unfailing sense of warmth, of new possibility, just as it does here.

Graizer deserves real credit for not allowing any element of sentimentality to enter his film, as it so easily could have done (the fact that an English-language remake is on the cards somehow raises alarm). Rather he has created a story that is coloured by a largely wordless grief, one from which two isolated individuals are struggling to emerge, their new connection offering a hint of consolation that The Cakemaker commendably leaves as an open question. The sotto-voce intonations of the piece are caught beautifully in its score from French composer Dominique Charpentier, the plangent piano elements of which perfectly express the subtle emotion of this small but highly accomplished film.

This Peccadillo release has as an extra Graizer’s 2007 12-minute student short, A Prayer in January, made in his first year of film school. (He later co-directed another short, La Discothèque, that went to Cannes in 2015, all the time developing The Cakemaker, which took some eight years to come to fruition – to “rise”, as it were – even though it was made on a micro-budget of $200,000). The kneading of dough – the physical rhythm of the hands shaping the material – plays an even more pronounced role in A Prayer in January, accompaniment to an almost wordless story of two men who seem to be in the course of a break-up (we learn nothing of their past, left to guess at the details of a shared life only from the immediate surroundings). It’s fascinating to see how a director, his concerns and motifs, has developed over the years – just as, in Graizer’s case, it will be to watch what he may transmute them into next.

Watch the trailer for The Cakemaker

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

Add comment