Rinaldo, Glyndebourne Festival review - teenage dreams | reviews, news & interviews

Rinaldo, Glyndebourne Festival review - teenage dreams

Rinaldo, Glyndebourne Festival review - teenage dreams

Stale stereotypes abound in a production that’s a bit past its sell by date

If you’d started senior school when this production premiered, you’d be finished by now and out in the world of work or at university, your first year days a distant memory. A lot’s changed since the curtain first came up on this version in 2011, and nearly a decade on, and in the wake of #metoo, Robert Carsen’s high school-set production feels more than a little out of date.

Carsen’s taken the plot of Handel’s 1711 opera - his first for the London stage - and transposed it into a 20th century classroom. Rinaldo is a schoolboy with a vivid imagination, who dreams up a world where he rescues and marries his crush, him and his chums are knights and he defeats his evil teachers. It looks great, although sometimes it’s a little unclear if Carsen’s trying to send a message, or just visually impress. A group of women dressed in niqabs and long black robes swirl on stage like whirling dervishes, before pulling off their outer layers to reveal short skirts, chains and fishnet stockings, transforming them into hyper-sexualised naughty schoolgirl stereotypes. Though some of the imagery seems a little pointless, the fickle nature of teenage desires are quite pertinent to the various shape-shifting and switching of loyalties that goes on in the opera.

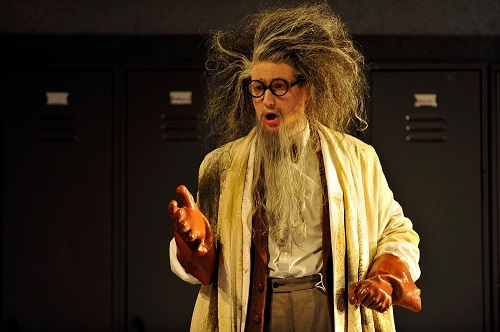

Such silliness, to be properly pulled off, needs to be impeccably executed, and this was an aspect of the production which could not be faulted. The stagecraft was slick and synchronised, and choreography completely solid. The Christian Magician in this production - sung by countertenor James Hall (pictured below) - is a crazed-looking chemistry teacher, who's controlled explosions provide a fun element of frisson. Sometimes though the showiness of it all was a bit too much, and overshadowed the music’s subtle, suggestive swagger.

In essence, the production’s all just a bit too silly. Which is a shame, because behind the needless flamboyance was some truly fantastic music making. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, under the baton of the young Russian conductor Maxim Emelyanychev - who is soon to take over as Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra - were on tremendous form, the rich timbre of their period instruments giving the music a burnished, golden hue.

In the title role, Polish countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński gave a sparkling performance, singing with lightness and clarity, displaying impeccable control when being flown from a bicycle at the end of act 1! His betrothed - Almirena - was beautifully sung by Giulia Semenzato. The Saracen queen Armida - or in this production, a stern teacher turned to pvc-clad dominatrix - was sung by Russian soprano Kristina Mkhitaryan, who performed the role with an assertive force, and duetted with Orlinski with a lustrous blend. Tim Mead’s Goffredo was light yet substantial, and Brandon Cedel sang the role of Argante with a robust strength. Musically, this was a splendid offering. It’s just a shame some of this was overshadowed by a production that's lost some of its relevance.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Comments

"Do we really need more