Edouard Vuillard: The Poetry of the Everyday, Holburne Museum, Bath review - dizzying pattern and colour | reviews, news & interviews

Edouard Vuillard: The Poetry of the Everyday, Holburne Museum, Bath review - dizzying pattern and colour

Edouard Vuillard: The Poetry of the Everyday, Holburne Museum, Bath review - dizzying pattern and colour

An artist's world encompassed

A beguiling collection of small paintings by Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940) forms an exhibition from his early career. It is a vanished world of domesticity in a Parisian flat, where Vuillard lived with his mother, a seamstress, for almost all his life. In his fifties, he told a friend that his mother was his muse.

Shy as he seemed to be, he did have a gift for friendship, and with his other artist friends, whom he had met when they all studied in the 1880s at the Académie Julian had formed the Nabis (Hebrew for prophet) with Bonnard and Maurice Denis. The Nabis' lively and committed passion for an appealing simplicity, coupled with a passion for colour and pattern, had been inspired by their admiration for the visual innovations of the controversial older artist, Paul Gauguin.

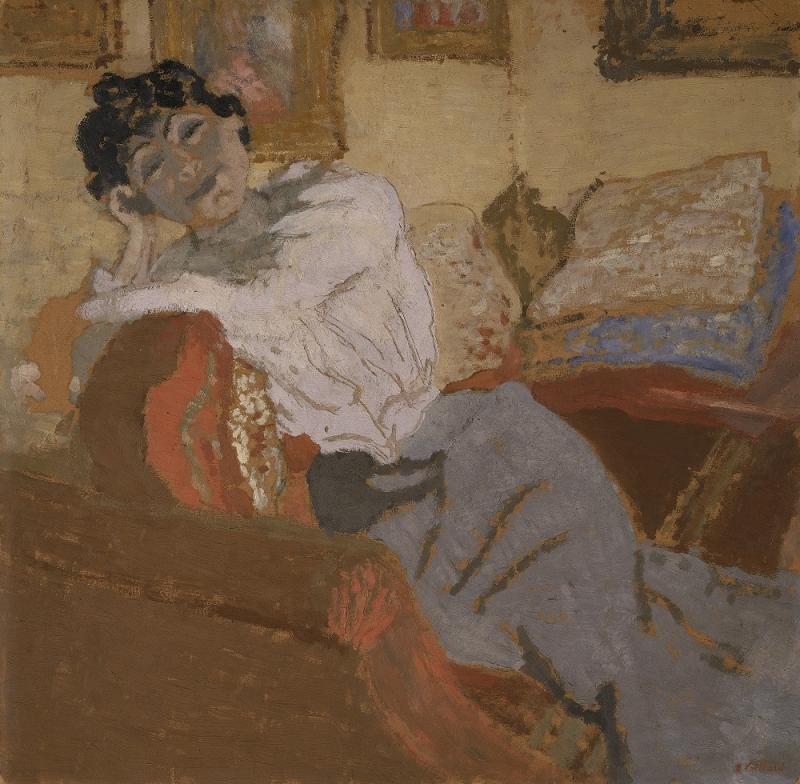

Although he loved women, Vuillard never married, but did have a deep relationship with several lively ladies at the heart of the intellectual life of Paris; his model and muse, Lucy Hessel, whose husband was the art dealer Jos Hessel, is shown in flirtatious mood in Madame Hessel on a Sofa, c.1905 (main picture). Oddly her face is more delineated than the ovals of his sister and mother, which are almost like Brancusi sculptures, suggestive but not detailed. Interestingly, unlike Bonnard and other artist colleagues he seemed to have no interest in pets, in cats and dogs.

Although he loved women, Vuillard never married, but did have a deep relationship with several lively ladies at the heart of the intellectual life of Paris; his model and muse, Lucy Hessel, whose husband was the art dealer Jos Hessel, is shown in flirtatious mood in Madame Hessel on a Sofa, c.1905 (main picture). Oddly her face is more delineated than the ovals of his sister and mother, which are almost like Brancusi sculptures, suggestive but not detailed. Interestingly, unlike Bonnard and other artist colleagues he seemed to have no interest in pets, in cats and dogs.

The pleasure of this wonderful exhibition, all from British public and private collections, and dating from Vuillard’s Nabi period in the 1890s, is the sense of such strong connections not only between the human inhabitants but the environments they have made. Madame Vuillard, arranging her hair, sits before a large mirror, her upright curved shape, comfortingly plump, clothed in the dizzying pattern of her purple and white dress emphasised by the more spacious pattern of the carpet and echoed by the delicate yet heavily patterned wallpaper, probably wall hangings that came with the various apartments rented by the Vuillards (pictured above right: Madame Vuillard Arranging Her Hair, 1900). The mass production of wallpapers and various ornaments was a feature of the period, and Vuillard wrote about how much he enjoyed observing in minute details decorative patterns and textures.

It is an immersive world, and when figures emerge out of the patterns we discern relationships, and even tensions. Every picture tells a story here, the story Vuillard intuits and even shows, and the story we tell ourselves when we look at the gossamer web of connections. The patterns of wallpaper and textiles, both repetitive and energised, surprising and inevitable, are somehow visual metaphors for human connections, too. Interiors are rarely observed straight on but obliquely; doors open at a slant to barely glimpsed rooms, a window opens out to a vista of roofs. In The Chat, 1893 (pictured below), his mother all in black sitting at right angles to her daughter in white seems to be having a formalised familial moment, embraced by the angled ceiling above. The Artist’s Sister with a Cup of Coffee sits, hands folded, for a quiet moment; a broom leaning on the wall behind, wallpaper and tablecloth providing visual movement, setting off the quietude of her expression, with light slanting in from the opening into a room behind which seems sunlit, softly aglow. These are quietly experimental paintings as well. Vuillard enjoyed using distemper, where pigment was bound with glue, a substance often used to paint walls; he painted on board, cardboard, millboard, paper laid down on panel or canvas. At the same time he was painting large decorative panels commissioned for the grand apartments of the well off progressive circles in which he moved.

These are quietly experimental paintings as well. Vuillard enjoyed using distemper, where pigment was bound with glue, a substance often used to paint walls; he painted on board, cardboard, millboard, paper laid down on panel or canvas. At the same time he was painting large decorative panels commissioned for the grand apartments of the well off progressive circles in which he moved.

Here is a whole world in small compass, claustrophobic on the one hand, comforting on the other. It is a world of dizzying patterns and kaleidoscopic colours described in dabs, swirls, blobs of paint. Blues, mauves, a range of blacks and greys, reds, pinks and yellows: these are the colours of a garden in bloom, but softened by the crepuscular light of a homely interior. It is a brilliant and emotional series of domestic sized paintings, which explains perhaps why a significant number here are rarely seen publicly, given how happily resident they are in private collections.

- Edouard Vuillard: The Poetry of the Everyday at the Holburne Museum, Bath until 15 September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment