theartsdesk Q&A: Vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant

theartsdesk Q&A: Vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant

The US jazz singer talks Bessie Smith, visual art, obsessive listening habits and more

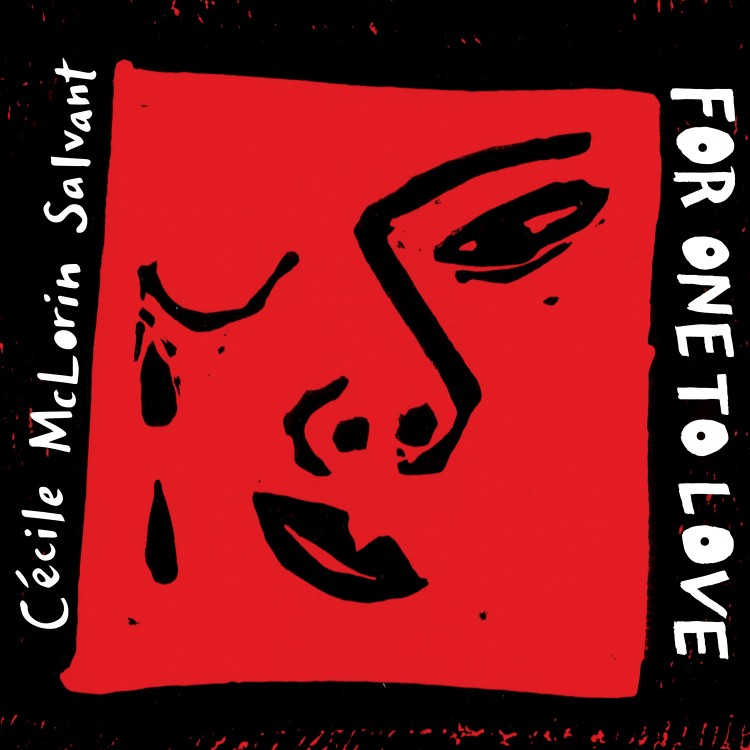

The vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant first came to the attention of the jazz scene when she won the prestigious Thelonious Monk International Jazz competition in 2010. In 2013, her Mack Avenue Records debut WomanChild garnered a Grammy nomination. Two years later, she picked up her first Grammy Award when her follow-up release For One To Love won Best Jazz Vocal Album.

Born in Miami to a French mother and Haitian father, McLorin Salvant started classical piano studies at five and began singing in the Miami Choral Society at eight. In 2007 she moved to Aix-en-Provence to study law as well as baroque and classical voice at the Darius Milhaud Conservatory. It was here she met reeds player and teacher Jean-François Bonnel. With his encouragement, she started to sing jazz and to immerse herself in the early blues and jazz vocal tradition.

Her repertoire contains some fascinating choices, from the 19th-century work song “John Henry” and the venerably ancient “Nobody” (first performed in 1906 in the Broadway production Abyssinia) to songs associated with the Empress of the Blues, Bessie Smith, as well as extended arrangements of songs from musicals (“Something’s Coming” from West Side Story) and opera (“Somehow I Never Could Believe” from Street Scene).

Released in September 2017, her third album for Mack Avenue Records, Dreams and Daggers, was recorded live over three days at New York’s Village Vanguard and in the studio at the DiMenna Center for Classical Music. The album topped the Jazzwise Albums of the Year poll (only the second vocal jazz album to do so, following Gregory Porter’s Water in 2011), was voted best vocal jazz album in the NPR Music Jazz Critics Poll, and has been shortlisted for Best Jazz Vocal Album in the 60th Grammy Awards.

PETER QUINN: All four of your albums to date have included songs associated with Bessie Smith. What is it about her music that you find so compelling?

CÉCILE McLORIN SALVANT: What I liked about her music is that it grew on me. When you're not used to hearing music of that quality and singing of that type, the first time you hear it, it can be almost violent – oh, what is this, it's gross. It grew on me. I learned not only to like it but to love it, and to want to bathe in it. It's like with people: when someone grows on you it's even stronger than if you liked them immediately and get slightly disappointed.

Another element is the strength and vulnerability that she has in her voice: the sheer power of her voice is just wild. The repertoire itself is amazing because it's so specific and yet universal. There are songs about floods, there are songs about hell, there are songs about sex, there are songs about food. There's this great song called "Black Mountain Blues" about this town where everyone is a total asshole. And the line is: "Back in Black Mountain a child will smack your face/Babies cryin' for liquor, and all the birds sing bass." And then the song is about how her man is the meanest man of that town.

Listen to Bessie Smith sing "Black Mountain Blues"

Is that element of humour and irony important in your own music?

I think it's incredibly important. Humour is the spoonful of sugar. You can defuse a situation, you can ask a rough question, you can be outrageous or inappropriate, and if you have some humour mixed in it, it's OK. Also, when people are laughing they come together. And I'm a person who really needs to laugh and cry – a lot.

The tracks on Dreams and Daggers recorded live at the Vanguard possess a real charge – were you conscious of this while you were performing?

All the sets we'd recorded were fine. You don't want it to be fine. You do want a vibe on it. We got to the second set of Sunday night – last night, last set – and I had nothing that I was excited about. Lawrence, the drummer in the band, huddled us together and kind of just yelled at us: "Guys, we've gotta talk. What the fuck are you guys doing? Let's get to our shit!" And we got it. Sunday, second set, something happened: we were sounding like ourselves.

There was family, there were musicians that we love – it felt like an environment of trust

The other thing that happens on Sunday night at the Vanguard – and this is a cliché – is people loosen up. It's the last set, you know, we're done. It's like an encore. And it was a fabulous audience. By Sunday night you've seen some faces who've come in twice. People come in on Tuesday and Sunday to get the full experience. There was family, there were musicians that we love – it felt like an environment of trust. So that made things easier, too.

Had you planned to do a live album or did circumstances just permit that to happen?

The Vanguard week was set up. And then I thought, hmmm, I could die, you know, maybe this is my only chance to play in this club ever in my life. Maybe it'll turn into a Sephora next week – New York will soon be called Sephora City. So I'm thinking, let's record this. Even though I don't feel ready and I feel like I'm a baby and I've no business being in this place. (Photo below left by Mark Fitton.)

The studio tracks with the Catalyst Quartet offer a pleasing counterbalance to the live material. Were you specifically aiming for that duality?

The studio tracks with the Catalyst Quartet offer a pleasing counterbalance to the live material. Were you specifically aiming for that duality?

I wanted a contrast: different textures, different feelings. Songs that were very direct and had a very clear meaning, and other songs that were hidden behind smoke and veils. In 2016, I did a concert with a string quartet and had such a great time that I thought it would be really fun to record this – we should do a whole string quartet album. And then the Vanguard happened, and I thought, rather than do one whole Vanguard album and one whole string quartet album, why not just combine them – as a reflection of what we've been up to sonically this year? And I like stuff that's got soft and hard.

It's funny, because as I was looking for a title for this album, I came up with a title that became the idea for another project that I'm now working on. And I love when things like that happen. So I was going to call the album L'Ogresse, the female ogress – and then I thought, no, that's its own thing. It's a song cycle that I'm writing all the music for, with arrangements by Darcy James Argue, this fabulous arranger. It's going to be very dark and moody. I'm very excited about it.

Your band has been together now for four years. The way they shape and inhabit the material, and their use of dynamics – does it allow you to take the music in any direction you want?

The places that we escape off to and that we don't have in common are actually really enriching

Maybe not any direction, because there are still some boundaries around what each of us can do and what each of us is interested in doing. But many directions. We have a lot in common, and the places that we escape off to and that we don't have in common are actually really enriching to what we bring to each other, I think. Aaron [Diehl] is a huge, obsessive fan of organ music, and I started to be aware of this instrument and to appreciate it through Aaron.

Are you always looking to draw in new sounds – I'm thinking of the accordion in For One to Love, and the banjo in WomanChild?

When it comes to instruments I love an underdog that no one likes. Of course the banjo has a beautiful history and they're beloved but they also have this stereotype which makes me love it even more. And the accordion is one of my treasured loves. And with the L'Ogresse project there's probably going to be some interesting instrumentation.

Songs such as “Fog” from For One To Love (pictured right) and “Somehow I Never Could Believe” from the new album seem almost painterly, a tableau of constantly shifting scenes. How important is visual art to you and how does it impact on your music?

Songs such as “Fog” from For One To Love (pictured right) and “Somehow I Never Could Believe” from the new album seem almost painterly, a tableau of constantly shifting scenes. How important is visual art to you and how does it impact on your music?

Visual art is the most important thing to me. It's funny: I feel like music chose me, jazz chose me, I just fell into it. But I choose visual art every day. It is an enormous joy. I love design, I love painting, I love sculpture, I love colour combinations. I know exactly what I like, what I want, visually. I do not know anything about what I want musically. I let myself be carried. I paint and draw a lot. Does it influence the music? I don't know – probably, but not in a way that I can tell. My appreciation for balance and humour is something that I revel in when I look at visual art: the incredible wood sculptor, Marisol, gorgeous and funny, and then Louise Bourgeois. It's not only funny, it's funny "and". Even somebody like Paul Klee, to me, has a great sense of humour.

Listen to Cécile McLorin Salvant perform “Fog”

In terms of your own composing, how does a piece start – with a melody line, an image, a snapshot of the whole?

There's no fixed process for me. Sometimes I write and I'll keep it in my phone or on my computer for a year. And then more often I'll sit at the piano and sort of linger there for a few hours and wait, and hope, and just improvise. And sometimes a melody will peak out. I feel like it would be easier if I kept at it on a regular basis, but I don't. Recently I moved so I didn't have the piano, and then when I'm on tour I don't write. I'm trying to figure out how, but I don't know how to write without a piano. Every time I get into a groove it's somehow cut by touring or by something else in my life. I'm going to have to figure it out, because I do want to get better at it and more comfortable – just know myself and my voice more.

The last time we met you were in the process of investigating the Gershwin Songbook. Was that fruitful?

I haven't finished going through it. This is the typical thing that I do: I set out a goal for myself and say, oh, I don't know all of Gershwin's music, or I don't know all of Ella's recordings. I'm going to listen to all of them. And I start it, and then I get sidetracked – oh wait, so-and-so sang this song? On this album? And then I'm gone, and I have to pull myself back.

I just remember being so deeply moved by him: the tone, the humour, the approach to improvisation

These days, I've been delving into Sonny Rollins. My goal – and I don't know if I'll make it through – is to listen to all of his albums, in order, day by day. Every day I listen to one album maybe three or four times in a row. The first time you hear an album doesn't count, you need a second time, the third time you hear something else, the fourth time something else. Sometimes what I'll do is listen to it twice in a row and then I'll choose one song and listen to that song 10 or 20 times in a row.

The other day we were waiting to get into a restaurant and I listened to this one track from East Broadway Run Down, which I love, over and over. Maybe it's making me a little crazy! But I just realised that it's what I did with Bessie Smith, and with Billie Holiday, without even thinking about it. So now I'm trying to direct it in a way that's a little bit outside what I know.

The first time I heard Sonny Rollins was when I was about 16, before I started singing jazz. I didn't even know his name. I heard him on that "Friday the 13th" track with Monk. I just remember being so deeply moved by him: the tone, the humour, the approach to improvisation. When you're 16 and you're not a jazz musician, you pick up on different things. I kind of miss that. I miss picking up on things in music as a lay person that's not a musician. I try to go back to that mindset but it's kind of hard.

Listen to “Friday the 13th" from Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins

Would it be true to say that if you hadn’t gone to study in Aix-en-Provence, you may never have become a jazz vocalist?

Oh, yeah, it was not an ambition of mine. It was an accident. That's why I'm always curious to know how people come to jazz. I came to it later than a lot of my friends, who at 10 years old were like, "Oh, I'm going to be a jazz musician." And I was like, "No. No one's alive playing jazz." That's what I thought, growing up in Miami.

Do you still have an opportunity to sing any baroque or classical music?

It's been six months since I've sung any, because of touring and the album, but the desire still burns with the same intensity, absolutely.

How will that be resolved, or can it be resolved?

I might have to just take some time, take lessons, and do a concert. Maybe record something that will be terribly received, and then move on.

You carry with you the things that move you

How has the study of baroque and classical music impacted on your singing?

You carry with you the things that move you. So there are some baroque songs that have turned me upside down emotionally. There's one by Gabriel Bataille, "Sortez soupirs témoins de mon martyre", one of those obscure gems of French baroque music. It's one of those songs you carry with you your whole life, from the moment you hear it. In terms of the influence that baroque singing has had on me, it's less the singing and more the teacher I had, who made diction and the text the most important thing. She was the first person to tell me, "Don't you know that all this music is doing is supporting the words and the story?" And I was like, oh really, that's great – because I've always wanted to be an actress.

Listen to “Sortez soupirs” by the French lutenist and composer Gabriel Bataille

But are you not being an actress in your musical life, when you’re on stage?

Sure. I'm getting that out of my system any way I can get it out of my system. But, you know, until I'm in a movie it'll always be ... I keep thinking why did I not pursue acting, which is what I really want to do. And slowly I realised that I would not have had good roles. I would have had horrible roles, or none at all, looking the way that I look. I mean I'm not Angelina Jolie, I'm not white, I'm not skinny, I don't have long hair. Everybody gets a nose job. I don't want to get a nose job! So that's one thing. The other thing is that the movie industry is just rough and gross.

In the current climate of populism and nationalism, what is it like being an artist in the US at the moment, in that atmosphere?

I don't know, I think I've sort of disconnected from everything that's political. I do not follow the news, I don't know what's going on. When the election happened, I think I was so shocked that my only defence mechanism was I'm not going to pay attention to any of this. If something terrible happens, someone will tell me. I do feel in a way all of this racism is that last, disgusting burp before we can be a little bit more calm.

I've always been interested in questions of identity and inequality, and why people feel like they should be in a certain role – like we're all acting in this weird play. It's very interesting to me. There are ways that we arm ourselves, I think, in order to just be able to live every day.

Watch Cécile McLorin Salvant perform "You're My Thrill" from Dreams and Daggers

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Add comment