'Before punk, there was Rauschenberg' | reviews, news & interviews

'Before punk, there was Rauschenberg'

'Before punk, there was Rauschenberg'

As a major retrospective opens at Tate Modern, musician and producer Justin Adams reflects on his lifelong love of an American great

In this cut and paste world, we have become used to a multiplicity of images: screens, words and pictures from across the globe and across history flicker through our field of vision, competing for our attention with the natural world, the urban environment and our own memories, thoughts and dreams. The artist who most successfully began to express this new vision of the world was Robert Rauschenberg.

In my teens in the Seventies, I was drawn to the bright colours of Pop Art in opposition to the murky palettes of the Old Masters. But Lichtenstein and Warhol's cool attractiveness seemed in the end to offer a critique of the modern world without much of a solution: "Isn't mass production soulless?" seemed to be the core message behind Warhol's electric chairs, dollar bills and Coke bottles (pictured below: Andy Warhol, Green Coca-Cola Bottles, 1962).

I discovered Rauschenberg through reproductions in books around the same time that punk rock hit. The prog rock album covers of Emerson, Lake & Palmer and Yes had depicted detailed kitschy fantasy worlds, but now the Pistols and the Clash were using collaged newspaper and silkscreened images of tower blocks, celebrating the grit of the city. Images of Rauschenberg's work that predated punk by almost 20 years seemed to chime perfectly – raw and handmade, I loved the fact that there was no attempt to prettify. His assemblages captured the exuberance of urban life where images come at you from all sides and piles of rubbish or car tyres co-exist with reproductions of Rubens or stuffed animals. Energy, irreverence, grime and a joy in the cheap and disposable were all common to punk and Rauschenberg. Teenage years are formative and, as I've been on the road around the States and in Europe, I've always been on the lookout for Rauschenberg's work. I've seen pieces in Stockholm, Los Angeles, New York and Cologne, and I keep finding new resonances. An early piece, called Mother of God, 1950, in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gives a clue that while Rauschenberg revelled in the everyday, his intentions were profound. Pages of grid-like maps are arranged and cut to form a large white circle or void in the centre of the piece. The intersecting lines of the map are like the pathways of the brain, suggesting logic and human activity, while the centre is a Zen-like void – the Mother of God.

Teenage years are formative and, as I've been on the road around the States and in Europe, I've always been on the lookout for Rauschenberg's work. I've seen pieces in Stockholm, Los Angeles, New York and Cologne, and I keep finding new resonances. An early piece, called Mother of God, 1950, in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gives a clue that while Rauschenberg revelled in the everyday, his intentions were profound. Pages of grid-like maps are arranged and cut to form a large white circle or void in the centre of the piece. The intersecting lines of the map are like the pathways of the brain, suggesting logic and human activity, while the centre is a Zen-like void – the Mother of God.

It is a contemplative piece, as transcendent as a Rothko, but with an inclusion of the everyday, the real modern world. In his later work Rauschenberg's messages become much more elusive and harder to define, but here he recalls Ginsberg in Footnote to Howl seeing transcendence in the materialistic buzz of the 20th-century American City.

I have a print of an untitled Rauschenberg at home. Living with it, I have come to see it as a kind of icon, a veneration of life forces, whose grid-like pattern of images is like a medieval altarpiece for the modern world. A spaceman, his backpack like an angel's wings, suggests man's aspiration, a shot of the Empire State building looking downtown shows New York, the inspirational city of the Fifties and Sixties – progressive and strong. An image of lit windows at night speaks of home and family, while a blurred camel in the Sahara is full of movement and the wild openness of the desert. Its juxtapositions defy any logic or direct interpretation: they are connected by line and colour, always fresh and spontaneous, and never losing their mystery.

I have a print of an untitled Rauschenberg at home. Living with it, I have come to see it as a kind of icon, a veneration of life forces, whose grid-like pattern of images is like a medieval altarpiece for the modern world. A spaceman, his backpack like an angel's wings, suggests man's aspiration, a shot of the Empire State building looking downtown shows New York, the inspirational city of the Fifties and Sixties – progressive and strong. An image of lit windows at night speaks of home and family, while a blurred camel in the Sahara is full of movement and the wild openness of the desert. Its juxtapositions defy any logic or direct interpretation: they are connected by line and colour, always fresh and spontaneous, and never losing their mystery.

Rauschenberg is rightly associated with New York, specifically Downtown in the Fifties and Sixties where he was part of a scene that included Jasper Johns, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. But earlier this year I met a Louisiana musician/artist/photographer called Dickie Landry who worked with Rauschenberg, as well Phillip Glass, Steve Reich and many others in New York in the Sixties. Dickie's link with Rauschenberg was as a fellow Southerner in NYC and they became friends.

Rauschenberg was born in Port Arthur, on the Texas/Louisiana border, and according to Dickie he loved to dance and party: "When did you ever see a photo of Warhol smiling?" he asked. Rauschenberg's art is infused with the loose funkiness of the South, where the meeting of European, African and Native American cultures was the spark for so much great American music and art. Perhaps his assemblages are a form of patchwork quilt, the quintessential American folk art, reusing materials to form personal memory maps of beauty and meaning (pictured above left: Monogram, 1955-1959).

Coming to Rauschenberg through punk he seemed ahead of his time, but in the 21st century again he seems prescient. Digital technology allows us to easily assemble found images: in the same way that the musical collages of Sgt Pepper or Lee Perry's dub masterpieces seemed to look forward to sampling technology, Rauschenberg's work, with its magpie bricolage, looked ahead to the borderless non-hierarchical world of Google images, and created poetry from a universe of imagery.

Coming to Rauschenberg through punk he seemed ahead of his time, but in the 21st century again he seems prescient. Digital technology allows us to easily assemble found images: in the same way that the musical collages of Sgt Pepper or Lee Perry's dub masterpieces seemed to look forward to sampling technology, Rauschenberg's work, with its magpie bricolage, looked ahead to the borderless non-hierarchical world of Google images, and created poetry from a universe of imagery.

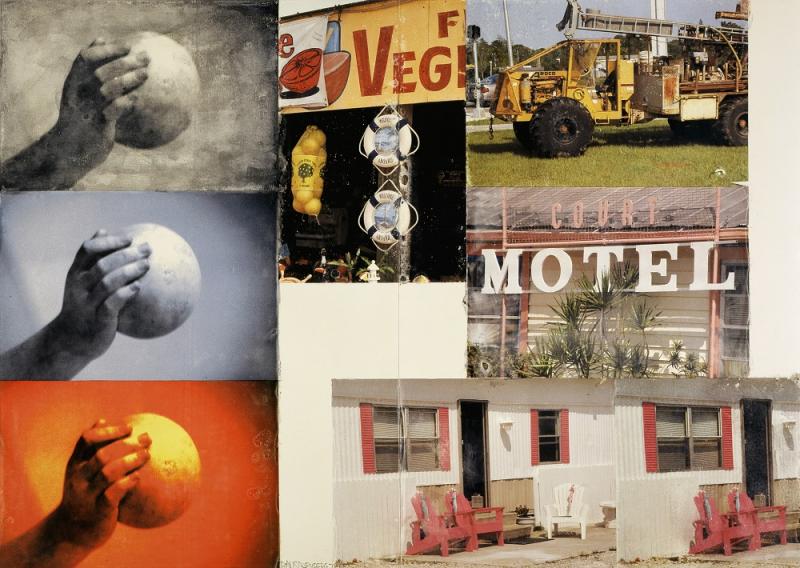

Famously he announced his intention to work "between art and life". Looking at his work we see the world around us with a new vision: texture, contrast and random collisions between materials and images become fascinating everywhere you look (pictured right: Stop Side Early Winter Glut, 1987). His original impulse to photograph every square foot of the United States was impossible, but we can understand the desire: it's an almost pantheistic way of looking at the world. Cézanne said of Monet: "only an eye, but my God, what an eye"; Rauschenberg recorded the world as he saw it, and my God, what a way to see it.

- Robert Rauschenberg at Tate Modern from Thursday 1 December until 2 April

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

GREAT POP ART RETROSPECTIVES

Allen Jones, Royal Academy. A brilliant painter derailed by an unfortunate obsession

Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery. An exhibition of still lifes which are anything but still

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

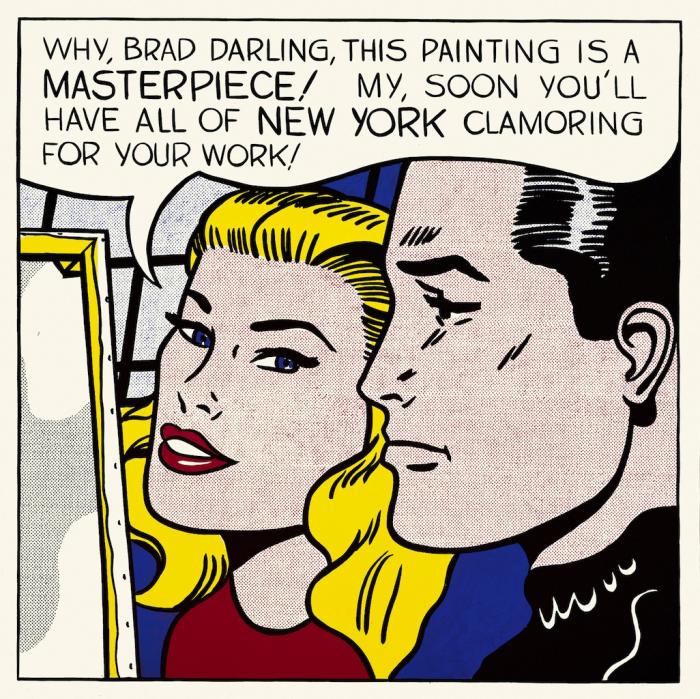

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Tate Modern. The heartbeat of Pop Art is given the art-historical credit as he deserves (pictured above, Lichtenstein's Masterpiece, 1962)

Patrick Caulfield, Tate Britain. A late 20th-century great emerges into the light

Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, Pallant House Gallery. The paintings are wonderful, but the curator does a huge disservice to this forgotten artist

Richard Hamilton, Tate Modern /ICA. At last, the British 'father of Pop art' gets the retrospective he deserves

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment