Portrait of the Artist, The Queen's Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Portrait of the Artist, The Queen's Gallery

Portrait of the Artist, The Queen's Gallery

A rich history of art through painters' eyes

Born in Rome and taught by her artist father, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652) led a colourfully energetic life. As an adolescent she was raped by her father’s assistant – an episode which unusually, then as now, actually came to public trial – but she nevertheless became a confident, resolute woman, and a successful artist.

Here Artemisia is almost hurling herself at her canvas, brush in one hand, palette in the other. Wearing an irridescent green silk dress, her black hair charmingly dishevelled, she is caught up in the intensity of her concentration (pictured below: Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, c.1638-9). No wonder she appears on the cover of the catalogue, setting the tone for one of the most absorbing exhibitions of the year.

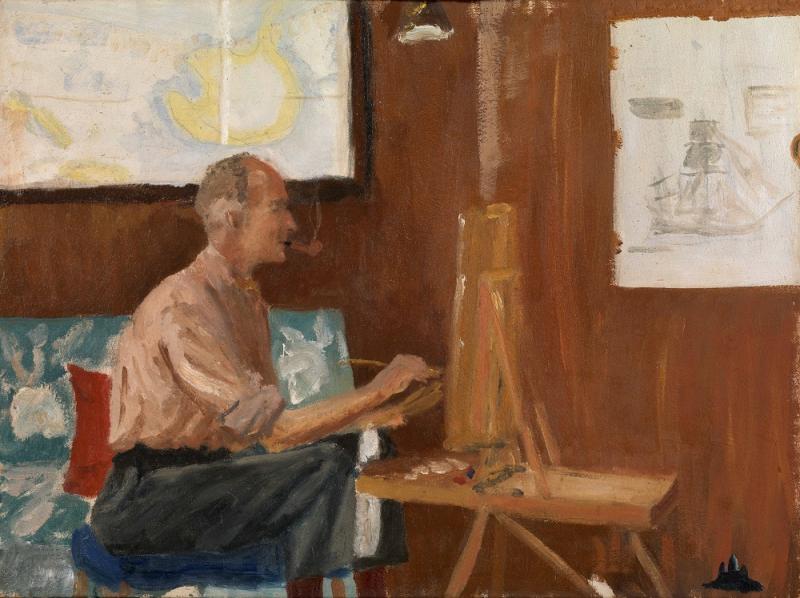

In several hundred paintings, drawings, miniatures, prints and photographs is a beautiful, magnificent and occasionally hilarious selection of artists depicting other artists, and also turning their gaze on themselves. It is a fascinating compilation, and nothing less than a history of western art seen through the eyes of those that made and collected it. The changing role and status of the artist, not to mention art, are explored across a wide spectrum, as we move from Rembrandt’s terrifyingly acute self-portrait to – say – Prince Philip painting his teacher, the skilled but anodyne Edward Seago (main picture). All levels are represented, from the sublime to agreeably attractive banality. The anthology makes us question not only a procession of styles and techniques, but what makes for quality, and the varying purposes of depiction.

In several hundred paintings, drawings, miniatures, prints and photographs is a beautiful, magnificent and occasionally hilarious selection of artists depicting other artists, and also turning their gaze on themselves. It is a fascinating compilation, and nothing less than a history of western art seen through the eyes of those that made and collected it. The changing role and status of the artist, not to mention art, are explored across a wide spectrum, as we move from Rembrandt’s terrifyingly acute self-portrait to – say – Prince Philip painting his teacher, the skilled but anodyne Edward Seago (main picture). All levels are represented, from the sublime to agreeably attractive banality. The anthology makes us question not only a procession of styles and techniques, but what makes for quality, and the varying purposes of depiction.

There are mighty studies of artists by themselves, self-portraits in the studio, searching analyses, and pieces of self promotion, flattering or searingly realistic. There are portraits by artists of other artists, and the anthology is neatly divided by theme rather than chronology: artists at work, artists playing a role, artists as objects of admiration, even as heroes.

Rubens (1577-1640) sketches himself in a moment in pen and chalk on rough paper – a 50something success subjecting himself to dispassionate scrutiny. It is an informal and seemingly spontaneous rendering, done just because he could. At the other end of the scale are two outstanding paintings, one an intelligently elegant self-portrait in a very dashing hat, given to Charles I in lieu of another painting the royal desired; also on view is Rubens’ portrait of his pupil, Sir Anthony Van Dyck, then only in his mid-20s. Both Flemish painters sport curled moustaches, flowing curly hair and carefully groomed beards; hippies can but envy such insouciant style.

From the same period are examples of the quintessentially English art of the miniature: a tiny self-portrait, in watercolour on vellum, of Isaac Oliver (1590?), in satin doublet, linen ruff and debonair high-crowned hat, and a far less formal one 30 years later by his eldest son Peter, an artist in Charles I’s household, charged with creating miniature copies of Old Master paintings for the king.

Two centuries and more on we have half-a-dozen renderings of Sir Joshua Reynolds, a master manipulator of his image, who painted 27 self-portraits often showing him modestly garbed. In a miniature copy of a painting gifted to the Royal Academy, his costume is more flamboyant, deliberately linking him to Rembrandt.

Two centuries and more on we have half-a-dozen renderings of Sir Joshua Reynolds, a master manipulator of his image, who painted 27 self-portraits often showing him modestly garbed. In a miniature copy of a painting gifted to the Royal Academy, his costume is more flamboyant, deliberately linking him to Rembrandt.

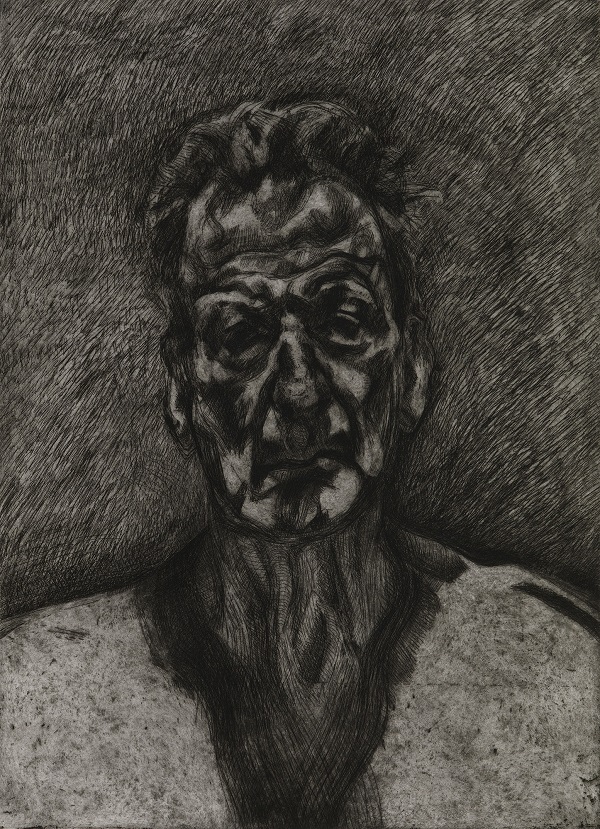

An enormous self-portrait (1996), dense and black, by Lucian Freud (pictured left) paradoxically the painter of a diabolically inept and ugly portrait of the Queen, was given to Her Majesty when Freud was made an OM; nearby hangs an enormous self-portrait (2012) by David Hockney, deadpan and peculiarly lifeless, also a presented to HRH when the artist was made an OM. There is little contemporary material on view and it is a pity that these are sub-par examples from outstanding artists.

A section called Artists at Work includes Zoffany’s dazzlingly virtuoso crowd scene from the 1770s, The Academicans of the Royal Academy shown perusing a pair of nude male models in the life drawing room. Zoffany’s other celebrated group portrait from the world of art is The Tribuna of the Uffizi, 1772, showing an informally choreographed group of male Grand Tourists – connoisseurs, collectors, and also artists – admiring the jam-packed hang of art treasures from the Medici collection originally in Florence. Commissioned by Queen Charlotte, herself of course German and Queen for more than fifty years, one aspect of this exhibition is to remind us of early internationalism in the arts.

Catering to passionate Victorian taste we have Sir Edwin Landseer’s The Connoisseurs: Portrait of the Artist with Two Dogs, 1860s, the dogs (a retriever and a collie) looking with admiring concentration over their master’s shoulder as he draws on a tablet held on his knee. Even more unexpected than Landseer’s faith in the wisdom of dogs is a 1870s photograph by Achille Melandri of the French actress Sarah Bernhardt, nattily attired in a white suit, her hair in an elaborate coiffeur, painting in her studio. Also on display is a Bernhardt self-portrait as a chimera, decorating a bronze inkwell: you couldn’t make it up.

Go and be intrigued: this is just a tiny sample of the variety on view, the myriad viewpoints into centuries of art. It is also perhaps a glimpse at how royal patronage of the arts, once so crucial, has shrunk as the art world has exponentially expanded. But we do owe the delights of the Queen’s Gallery to a new ordering of royal relationships to the public at large.

- Portrait of the Artist at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace until 17 April 2017

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment