Oedipe, Royal Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Oedipe, Royal Opera

Oedipe, Royal Opera

Tragedy transcended and patience rewarded in Enescu's epic myth

"Unjustly neglected masterpiece" is a cliché of musical criticism, and usually an exaggeration.

There's a big story to be told here: not just that of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, as in Stravinsky’s opera-oratorio, but its unfortunate protagonist as the subject of the original Sphinx's riddle ("What walks on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon and three in the evening?"). In Act One, he'd be on all fours if that baby were animatronic. He stands just about upright on two, and then finally on three when Antigone gives her self-blinded father a stick as fellow guide. Àlex Ollé and Valentina Carrasco are hugely ambitious in their approach, wanting the best of all possible worlds: monumental and intimate, timeless and of the present.

As the dropcloth rises, you really can't believe your eyes until this frieze on a terracotta surface (pictured above) finally comes to life. But there's the first of several scenic prices to be paid for that coup – no room for dancing, which means a cut of five minutes of some of Enescu's best purely orchestral music (and the first music of the opera to be heard in concert in 1924, 12 years before the long-delayed premiere). In the long and eventful second act, nothing can quite match the visual imagination inherent in the score: I hear a bare, bleached landscape with shepherd's pipings for the scene at the crossroads where Oedipus slays his father, but this is a murky mess of dry ice and night-time roadworks where you can't really see what's going on.

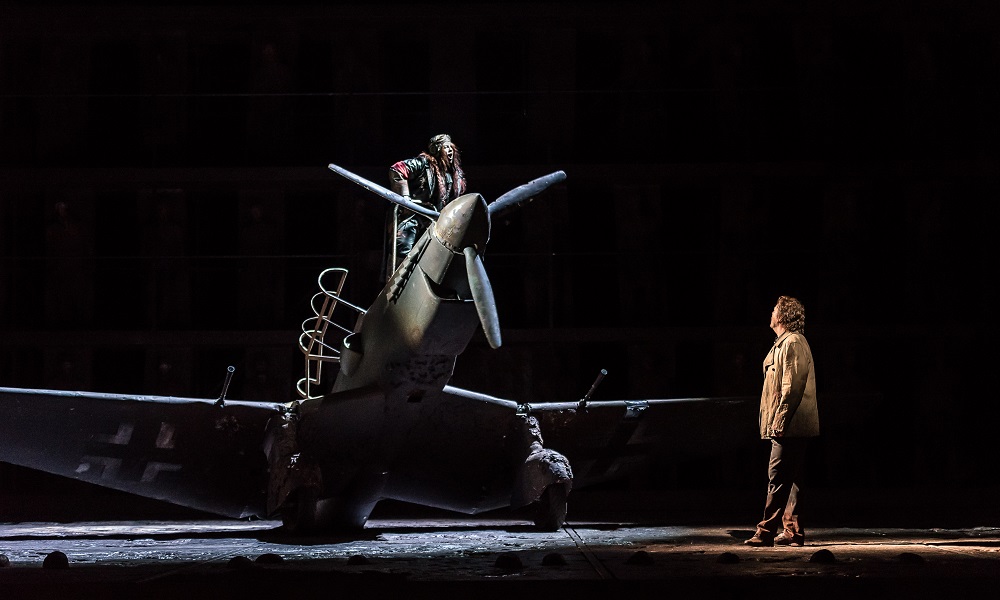

The Sphinx is far more scary in her outlandish, near-atonal music than what we see, a wild woman piloting a Second World War plane (pictured right). Enescu and his librettist make a rare departure from their tragic source by having her ask "What is greater than destiny?" to which Oedipus replies “Man”, and his adversary dies laughing. It's a terrifically inflected performance from astounding contralto Marie-Nicole Lemieux, in one of at least 10 roles which have a short stage life but need to make their mark.

The Sphinx is far more scary in her outlandish, near-atonal music than what we see, a wild woman piloting a Second World War plane (pictured right). Enescu and his librettist make a rare departure from their tragic source by having her ask "What is greater than destiny?" to which Oedipus replies “Man”, and his adversary dies laughing. It's a terrifically inflected performance from astounding contralto Marie-Nicole Lemieux, in one of at least 10 roles which have a short stage life but need to make their mark.

Only one, Alan Oke's Shepherd, doesn't quite make the impact he should. There are two very impressive basses at different ends of their careers, In Sung Sim as Phorbas, the catalyst of the tragedy from Oedipus’ birth city of Thebes, and ever-stentorian John Tomlinson as voice of doom Tiresias. Claudia Huckle has the right warmth for anxious adoptive mother Merope, to whom Oedipus confesses his fears on the Freudian couch, one of several ideas not entirely made clear in the action; you have to read Ollé's programme note for enlightenment. You'd probably get the Xian and the Hungarian toxic mudslide references straight off, though.

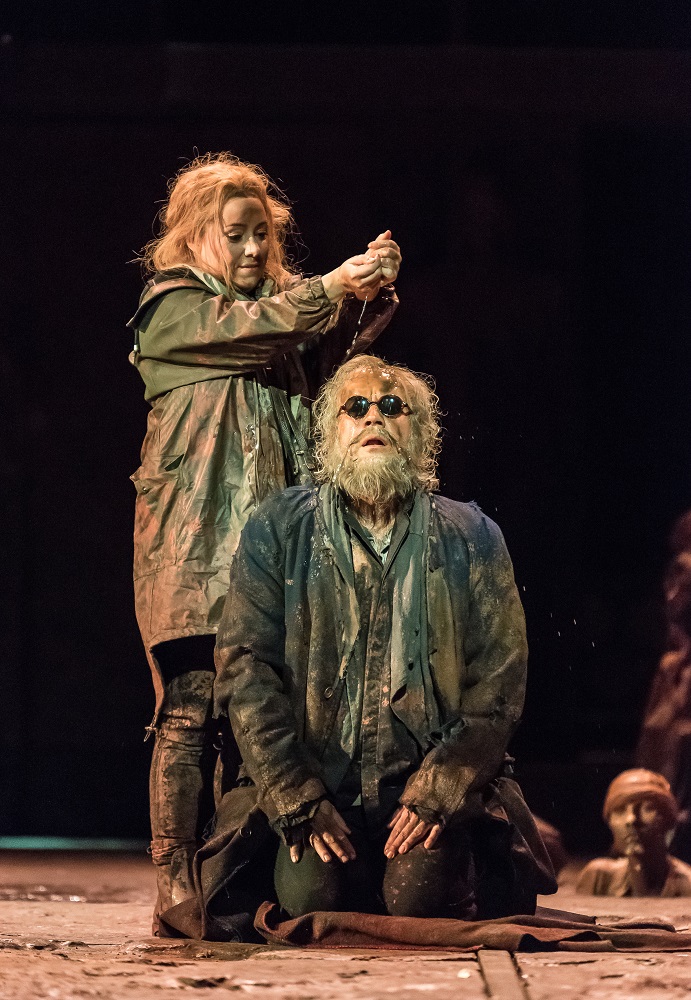

Sarah Connolly (pictured left with Johan Reuter) laces Jocasta's reproaches with voluptuous terror in a third act which is so different from Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex, the same Sophoclean territory covered more swiftly by Enescu with an unerring sense of ebb and flow. Its denouement is screwed to an unbearable tension in Oedipus's sung-spoken curses and softened by the only voice which can provide balm after an hour and a half of darkness and mystery: the soprano singing Oedipus's daughter Antigone with her melting repetitions of "Je te suivrai", perfect casting for Sophie Bevan.

Sarah Connolly (pictured left with Johan Reuter) laces Jocasta's reproaches with voluptuous terror in a third act which is so different from Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex, the same Sophoclean territory covered more swiftly by Enescu with an unerring sense of ebb and flow. Its denouement is screwed to an unbearable tension in Oedipus's sung-spoken curses and softened by the only voice which can provide balm after an hour and a half of darkness and mystery: the soprano singing Oedipus's daughter Antigone with her melting repetitions of "Je te suivrai", perfect casting for Sophie Bevan.

The music joins her incandescence in the great epilogue of redemption, essentially Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus through the filter of Wagner's Parsifal Act Three (Bevan's Antigone anointing Reuter's Oedipe pictured below), and it’s the melting new idiom here which is the payoff to the horror-movie gestures of earlier acts (“Like a 1940s biblical film score,” said a fellow audience member, and he wasn’t wrong: late romantic music was a huge resource for European composers who emigrated to Hollywood). It’s a pity that Ollé and Carrasco stick with their terracotta theme instead of allowing the scenery to green and follow the musical pastoral. That involves another cut of crucially beautiful invention here, along with the sound of a pre-recorded nightingale. But the mystery of Oedipus’s final merging with the elements is ultimately very strong and moving.

This fourth act is Leo Hussain’s finest stretch as a conductor of the hugely complex orchestral writing (surprising that Royal Opera Music Director Antonio Pappano didn’t want this one for himself). There’s plenty of textural clarity throughout, but the Royal Opera Orchestra doesn’t yet capture Enescu’s lurid glow for the more terrible events, and the finale of Act Two, when Thebes welcomes the sphinx-slayer, fails to pack the necessary punch. The chorus provides the right wall of sound when necessary but will hopefully become more precise over the run. Worth noting, all the same, that this is a big work for the chorus, of which there's not a single specimen in ENO's 2016-17 season.

This fourth act is Leo Hussain’s finest stretch as a conductor of the hugely complex orchestral writing (surprising that Royal Opera Music Director Antonio Pappano didn’t want this one for himself). There’s plenty of textural clarity throughout, but the Royal Opera Orchestra doesn’t yet capture Enescu’s lurid glow for the more terrible events, and the finale of Act Two, when Thebes welcomes the sphinx-slayer, fails to pack the necessary punch. The chorus provides the right wall of sound when necessary but will hopefully become more precise over the run. Worth noting, all the same, that this is a big work for the chorus, of which there's not a single specimen in ENO's 2016-17 season.

You may, like many spectators I overheard at the interval, find the going just a bit too tough in the first two acts and feel like bolting (don't). What keeps the difficult second act especially alive is Johan Reuter’s tireless characterisation of the immense title role, going one stretch further than his magnificent performance in Nielsen's Saul and David in Copenhagen. It needs Wagnerian bass-baritone stamina, and at one point Enescu thought of asking Chaliapin to sing it, though the singer was in his sixties at that point and had to decline.

Reuter never falters, though the production robs him of something of his clear-eyed facing up to fate by making him a drunk at the crossroads (yes, you'd drink too if you had that awful knowledge of your fate from Apollo, but that's not really the point of this tragic hero). The climactic Thebes act alone would finish off most singers, but this one has to find new reserves for the final Eleusinian mysteries. Reuter’s Oedipus really does transcend his destiny. It’s a payoff worth waiting for: stick with Enescu, and you may end up wanting to see his strange and various masterpiece again. Catch it while you can.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

Add comment