The Dark Mirror: Zender's Winterreise, Barbican Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

The Dark Mirror: Zender's Winterreise, Barbican Theatre

The Dark Mirror: Zender's Winterreise, Barbican Theatre

Less a remix of Schubert's song-cycle than a fascinating conversation with it

Elasticity is a surprisingly reliable test for great art. How far can you stretch, bend, or reshape a work before it loses its essence, its identity? Hamlet, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Antigone, Pride and Prejudice can all take almost anything you can throw at them, but what about Winterreise, Schubert’s song-cycle of lost love?

Katie Mitchell has dehumanised it in her staged interpretation, One Evening, Thomas Guthrie has explored the identity of the poet-lover in his puppet-driven version for New Kent Opera, David Alden has made a television film of it for Channel 4, and now director, designer and video artist Netia Jones stages not Schubert’s own cycle but a contemporary reimagining of it by composer and conductor Hans Zender.

In Hans Zender’s “composed interpretation” of the score (played herew by the excellent Britten Sinfonia under Baldur Bronnimann), Schubert’s music finds itself refracted through musical history. The singer and his songs remain all but unchanged, a musical rope lashing us to the original work, but around them instrumental textures swirl and shift, and music once so rooted in a particular time and place starts to try on different identities for size.

In Hans Zender’s “composed interpretation” of the score (played herew by the excellent Britten Sinfonia under Baldur Bronnimann), Schubert’s music finds itself refracted through musical history. The singer and his songs remain all but unchanged, a musical rope lashing us to the original work, but around them instrumental textures swirl and shift, and music once so rooted in a particular time and place starts to try on different identities for size.

Zender’s chamber orchestra features only four strings, taking its dominant sound-colour instead from the wind section, whose predictable members are joined by an oboe d’amore, bass clarinet and a saxophone. A large percussion section, a guitar, harp and accordion, also add their voices to an ensemble that constantly reinvents itself, moving from Biedermeier string trio to folk-band, chugging wind-band or a cinema orchestra of sound-effects.

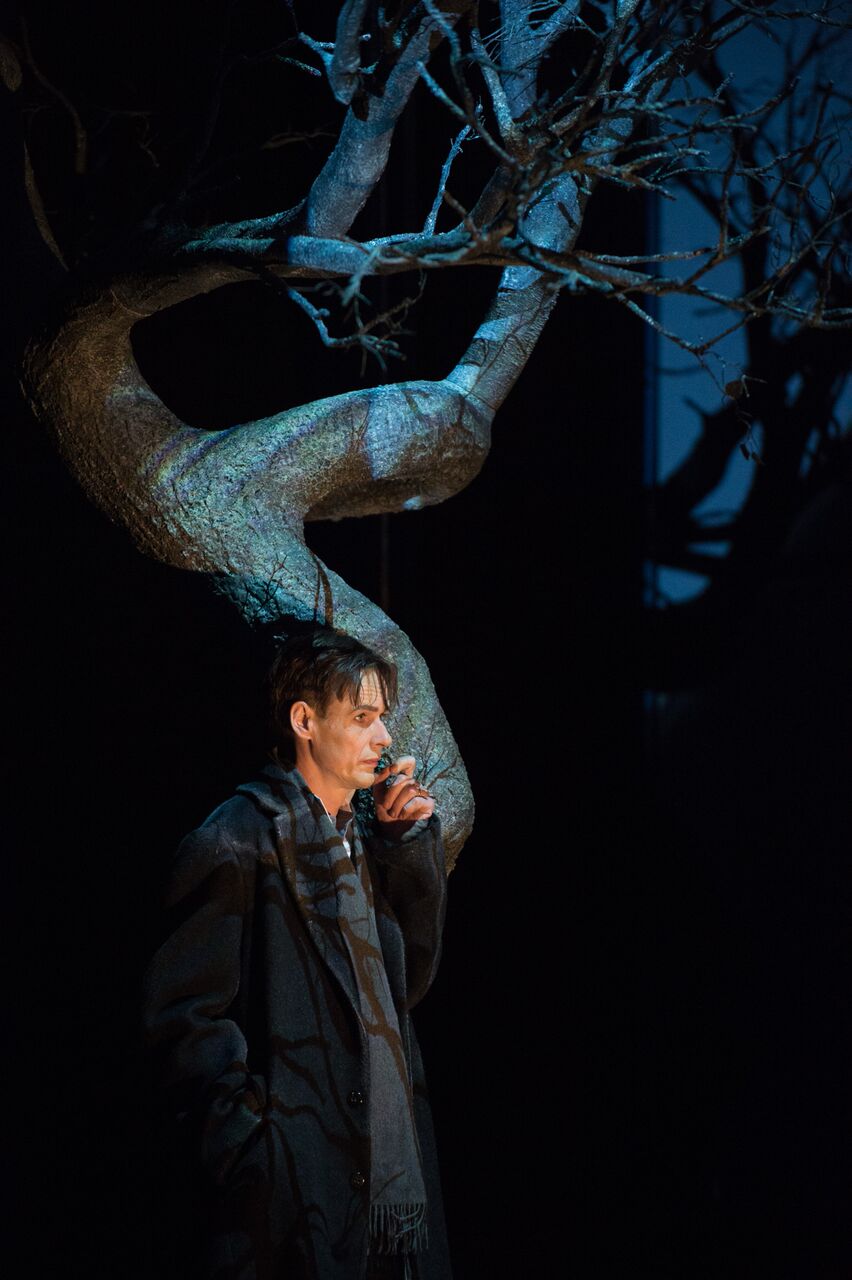

A diagonal platform sets him constantly at odds with the space around himBut if the music roams across the decades, Jones’s visuals are more rooted. A video screen, divided into jagged panels like a shattered mirror, replays the story of the young wanderer – private memories projected for all to see. Using footage from Alden’s 1997 television film, Jones is able to play the young Bostridge off against his real-life 50-something counterpart (pictured above right), an effect as uncanny as it is playful, a doppelgänger for the digital age.

There’s an expressionist intensity and a cabaret directness both to Schubert’s songs and Zender’s reimagining, and Jones gives us a wanderer who is pure Weimar nightclub. Hair black with pomade, face white with powder, echoing the monochromes of his white tie and tails, Bostridge cuts a sinister figure – an embittered, solitary man who sits alone and broods on past sufferings and wrongs. A diagonal platform sets him constantly at odds with the space around him, forever forcing his either to toil upwards against a steep incline, or risk slipping and sliding down against his will.

To take so contained, so intimate a work, where every note is weighted and judged for both dramatic and musical effect and explode it into this widescreen, cinematic spectacle is to risk losing its emotional core. But Jones doesn’t overwork her materials. Projections are kept generic – snowy landscapes, a river, frozen branches – refusing to commit to anything as literal as a backstory for this failed love affair. This helps throw the attention where it belongs, onto Zender’s wonderful musical dialogue with Schubert’s cycle.

His reworking goes far beyond mere orchestration, stretching some passages out of shape, denaturing their sounds into hollow wooden and metallic noises, colouring others so richly and specifically that they take on an entirely new character from their originals. It’s like seeing a familiar face in a cubist painting. “Der Lindenbaum” pairs soft strings and accordion, filling out cloudy, widely-spaced chords with dubious harmonic additions – a musical memory that can’t quite summon the details correctly. “Der Leiermann” goes further. While the voice stick’s to Schubert’s melody, each orchestral interjection is reworked, taking it harmonically further and further away from a singers who doggedly sticks to his guns. It’s a beautiful piece of musical theatre.

His reworking goes far beyond mere orchestration, stretching some passages out of shape, denaturing their sounds into hollow wooden and metallic noises, colouring others so richly and specifically that they take on an entirely new character from their originals. It’s like seeing a familiar face in a cubist painting. “Der Lindenbaum” pairs soft strings and accordion, filling out cloudy, widely-spaced chords with dubious harmonic additions – a musical memory that can’t quite summon the details correctly. “Der Leiermann” goes further. While the voice stick’s to Schubert’s melody, each orchestral interjection is reworked, taking it harmonically further and further away from a singers who doggedly sticks to his guns. It’s a beautiful piece of musical theatre.

Bostridge has been singing this music now for 30 years, and his interpretation has changed again and again through performances and two different recordings. What’s interesting here is yet another shift in approach. While Bostridge’s more recent recitals have seen a brutal, barely-sung intensity to his delivery, repeatedly sacrificing beauty of line for emotional immediacy, here we lose some of that. It’s as though, supplemented by Zender and Jones, the tenor feels less need to underline his point, and so reverts to a rather more smoothed-out delivery – less interesting in itself, but a more yielding foil for everything else going on around it.

Neither Jones nor Zender makes any attempt to improve on Schubert’s original, and that’s the root of this show’s effectiveness. Instead, both sustain a dialogue with it, interrogating, interjecting, supplementing and, occasionally, diverging, to create something new – a commentary on a classic.

- The Dark Mirror at the Barbican until 14 May

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Add comment