Corin Sworn: Max Mara Art Prize for Women, Whitechapel Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Corin Sworn: Max Mara Art Prize for Women, Whitechapel Gallery

Corin Sworn: Max Mara Art Prize for Women, Whitechapel Gallery

Impostors and stolen identities explored in an installation inspired by the Commedia dell’Arte

Glasgow-based Corin Sworn is the fifth winner of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women. Every two years a British artist is chosen on the basis of a proposal, rather than existing work. The fashion house then supports the project with funding, a bespoke, six-month residency in Italy and, following the Whitechapel Gallery show, an exhibition at the Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia, where the HQ of the family-run business is located.

It's an extremely enlightened form of patronage, but its emphasis on process rather than product is risky. Since artist’s projects are likely to change course en route, inevitably the outcome is unpredictable and Sworn’s project is no exception. Her proposal was for a video piece about the Commedia dell’Arte, a popular form of street theatre that originated in Italy in the 1550s. Players generated their own material through improvisation and, since nothing was recorded, no scripts or contemporary descriptions of sketches exist to allow one to recreate a historical performance.

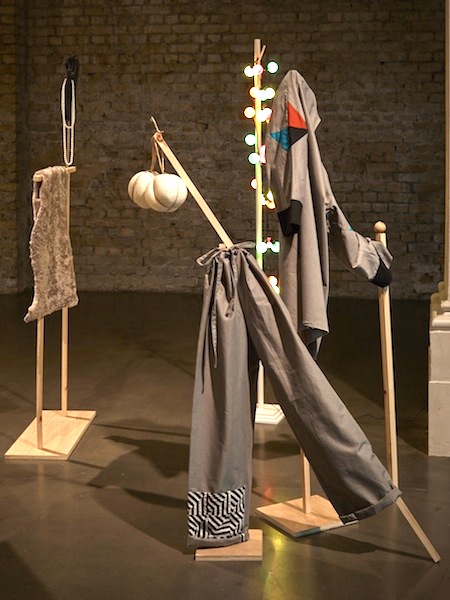

The troupes were continually on the move, so rather than using cumbersome scenery, they relied on clothing and props to set each scene. Sworn’s research eventually led her to a list of props used in a production; finally she had something concrete to go on and decided to recreate the props as an installation. Among the items on show are candles, wine bottles, bundles of sticks, a rope ladder, a wooden sword, club, rope and loaf of bread plus a toy fox, rat and rabbit and their desiccated counterparts. No attempt has been made to fake the patina of age; the wine bottles, soft toys and candles are unashamedly modern. So are most of the clothes on display; acrobatics and clowning formed a key part of Commedia dell’Arte performances and the cloaks, tunics and pantaloons that were made for her by Max Mara are loosely based on clown costumes (pictured above right).

The troupes were continually on the move, so rather than using cumbersome scenery, they relied on clothing and props to set each scene. Sworn’s research eventually led her to a list of props used in a production; finally she had something concrete to go on and decided to recreate the props as an installation. Among the items on show are candles, wine bottles, bundles of sticks, a rope ladder, a wooden sword, club, rope and loaf of bread plus a toy fox, rat and rabbit and their desiccated counterparts. No attempt has been made to fake the patina of age; the wine bottles, soft toys and candles are unashamedly modern. So are most of the clothes on display; acrobatics and clowning formed a key part of Commedia dell’Arte performances and the cloaks, tunics and pantaloons that were made for her by Max Mara are loosely based on clown costumes (pictured above right).

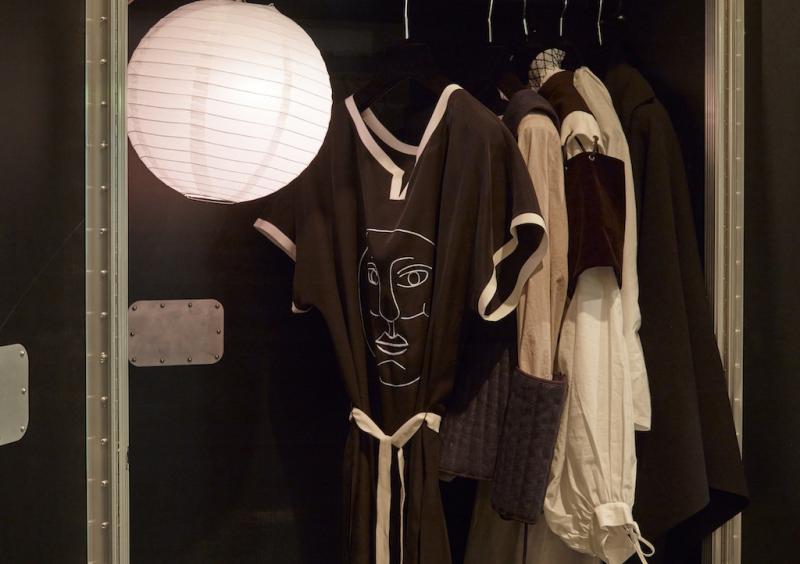

How to show these items, though – packed in a trunk, laid out ready for use or arranged as though in a museum display? Sworn’s solution is an uneasy mix of the three. The objects are distributed on specially made benches, stands and podiums devoid of period features and painted pale grey to make them as neutral as possible. A bright yellow plastic bucket adds an unrepentantly contemporary note to the display; so do the high-tech cabinets which contain the Renaissance-style shirts and doublets worn by two acrobats who appear on video within the display. To confuse things further, a Chinese paper lantern illuminates their period costumes (main picture).

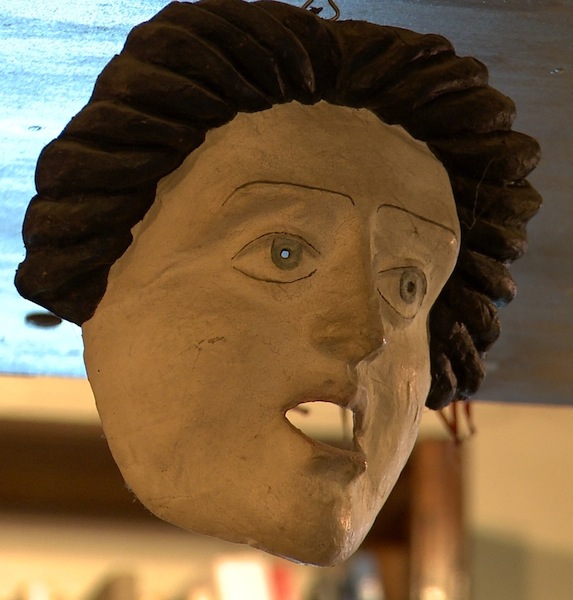

The players wore masks (pictured below left) to portray stock characters such as cunning servants, miserly masters, vainglorious military men and star-crossed lovers. To thicken the plot and create general hilarity, women frequently dressed as men and characters borrowed each other’s clothing so that identities were confused, roles reversed and power relations upended. Sworn became fascinated by this exploration of identity and the questioning of social status that formed a key ingredient of Commedia dell’Arte performances and, frustrated by the lack of information – “trying to come to terms with something that is no longer accessible”, as she put it – she turned to a real-life example of mistaken identity that had captured the popular imagination at the time.

Over speakers, we hear the story of Martin Guerre, a Basque peasant who left his wife and child in 1548 and disappeared from Artigat, the village in south west France where they lived. Eight years later, a man claiming to be Guerre arrived in Artigat, moved in with Guerre’s wife, Bertrande and had two children with her. After three years, though, he was denounced as an impostor and brought to trial.

Over speakers, we hear the story of Martin Guerre, a Basque peasant who left his wife and child in 1548 and disappeared from Artigat, the village in south west France where they lived. Eight years later, a man claiming to be Guerre arrived in Artigat, moved in with Guerre’s wife, Bertrande and had two children with her. After three years, though, he was denounced as an impostor and brought to trial.

Of the 150 people questioned as witnesses, some were convinced he was genuine, others thought him a fake, but many simply weren’t sure. Eventually, the real Martin Guerre returned and the cuckoo was found guilty and hanged for adultery and fraud. This compelling tale of deception illustrates the power we have in real life, as well as in performance, to shape other people’s perceptions of ourselves.

It's ironic that the most arresting aspect of Sworn’s installation bears only a tangential relationship to the subject she set out to research. Her project still feels like a work in progress and it wouldn’t surprise me if, in the future, it were to split into two parts, one based on the Commedia dell’Arte and another exploring issues of identity – whether mistaken, exchanged, stolen or redefined – that are still so relevant today.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Comments

I like Sarah Kent's