Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015): A virtuoso remembered | reviews, news & interviews

Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015): A virtuoso remembered

Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015): A virtuoso remembered

Memories of a maverick pianist and composer of 80-minute homage to Shostakovich

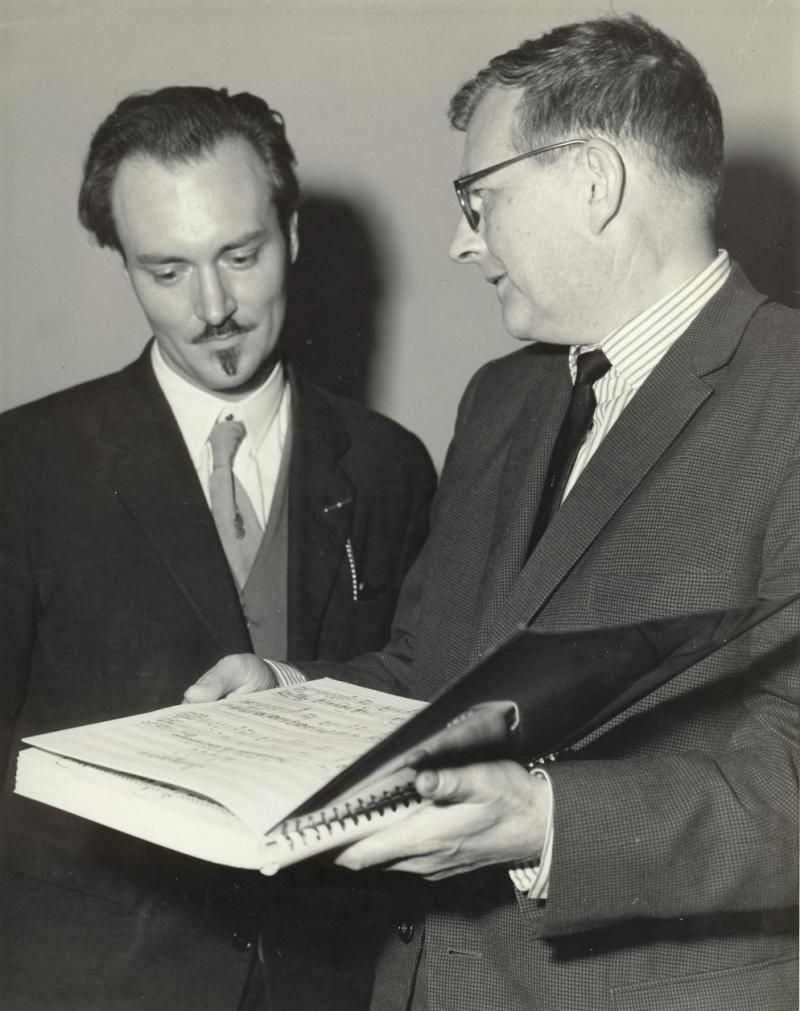

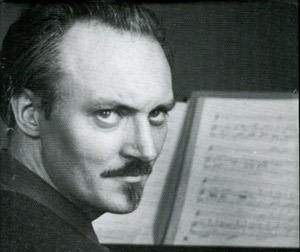

Ronald Stevenson, who died on Saturday at the age of 87, was a composer and pianist who will be much missed both in the small Borders village where he lived and by the much larger musical community in Scotland and beyond. As a composer he was unashamedly rooted in the late 19th Century tradition of intellectual pianism – in his music you can trace a line of descent from Bach to Liszt through his great hero Busoni.

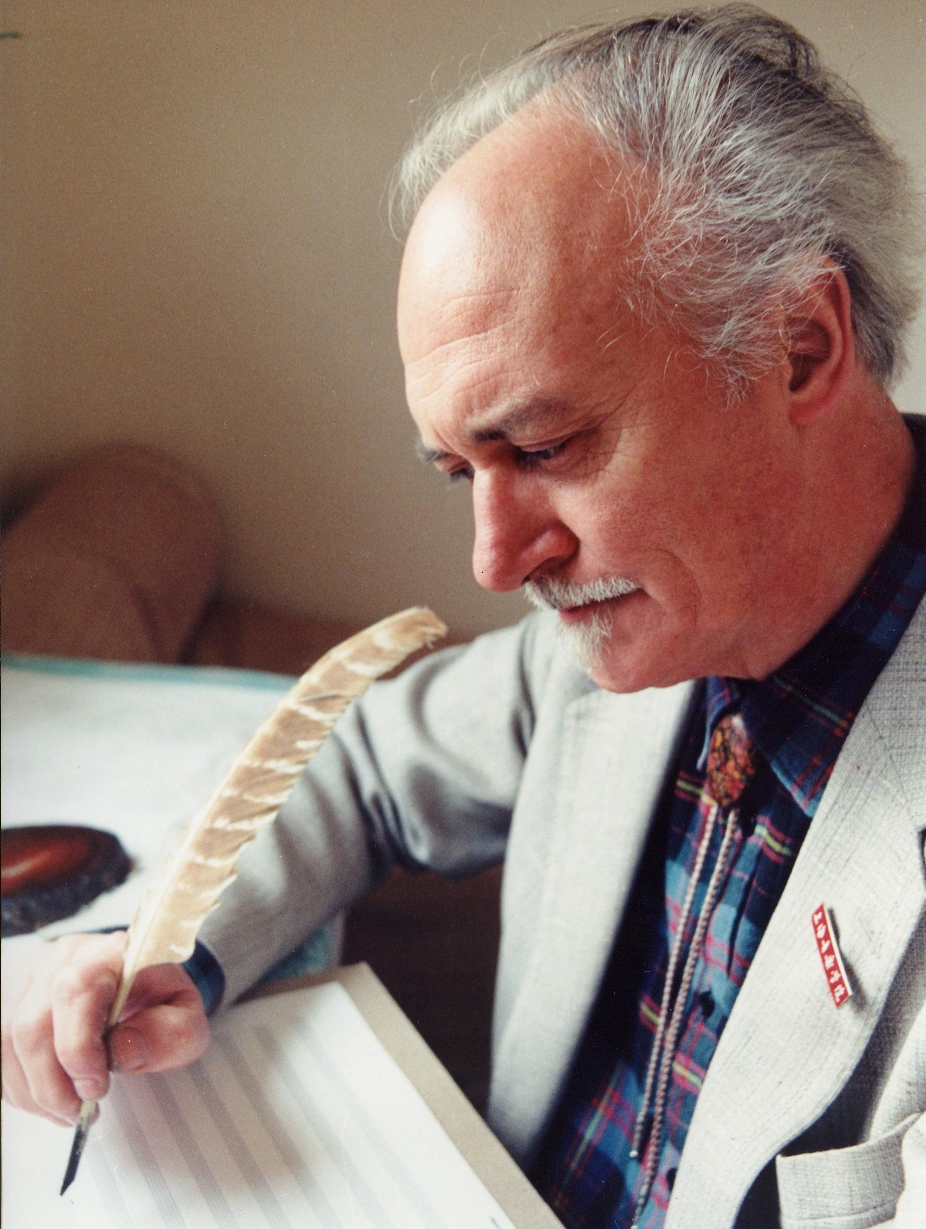

I feel greatly privileged to have known Ronald for about the last 35 years. In the early 1980s when I worked at the BBC as a recording engineer in Edinburgh, Ronald would sweep into our magnificent music studio with his characteristic cowboy tie, black fedora, and a flowing Lisztian cloak. He was dramatic before the music even began. I was somewhat in awe of this rather formidable figure but he was kind and patient with the seemingly endless process of capturing his performance on quarter inch magnetic tape. He was a fabulous pianist.

As gamekeeper turned poacher, I found myself some years later writing about his music. His 1992 Violin Concerto was commissioned and conducted by Yehudi Menuhin but attracted interest in the press chiefly because of its length. I rang up Ronald. “I hope you won’t make infantile remarks about its being long,” he said. “Of course it’s long, it contains the entire history of western fiddle music.”

As gamekeeper turned poacher, I found myself some years later writing about his music. His 1992 Violin Concerto was commissioned and conducted by Yehudi Menuhin but attracted interest in the press chiefly because of its length. I rang up Ronald. “I hope you won’t make infantile remarks about its being long,” he said. “Of course it’s long, it contains the entire history of western fiddle music.”

Stevenson is probably best known for another monumental work, his solo piano Passacaglia on DSCH, an uninterrupted homage to Shostakovich that lasts about 80 minutes. It is not often performed – John Ogdon was a champion – and at the only performance I have heard I found Ronald in a fury afterwards as the pianist, whose name luckily escapes me, had made so many unauthorised cuts.

Some time after that I went to see Ronald in his charming village house in the very heart of West Linton. He guided me into a small room dominated by a large piano. “Welcome to my den of musicquity,” he said. On the piano was his recently completed Festin d’Alkan, and the walls were crowded with memorabilia, photographs, letters, manuscripts. He revealed then that all his life he had corresponded with any composers willing to reply to his letters, and he had accumulated a vast stash of unique correspondence. There were letters from Walton, Percy Grainger (with whom he struck up a particular epistolary friendship), Alan Bush, Bliss, Britten, Stokowski, and even Sibelius, though sadly the latter exchange did not progress beyond polite formalities. The correspondence, which became the focus of a long article in the Daily Telegraph, is now lodged in the National Library of Scotland.

Advancing years brought a familiar litany of frailty and illness. I went to Ronald’s 80th birthday party only to arrive shortly after he had, to everyone’s delight, played some Busoni on the piano. After that, he was not often to be heard performing. But he told me once of a visit to hospital shortly after a mild stroke. The doctor had asked Ronald to demonstrate that he could move each of the fingers on his hand. Ronald went one better, and asked “doctor, can you do this?” and played on the tabletop, at speed, one of those excruciating five finger piano exercises that professional pianists do in their sleep. The doctor was silent.

I last saw Ronald shortly before Christmas, when he came to the Broughton Choral Society concert, at which we were performing a short piece called The Dream, by Savourna. He was as charming as ever and everyone remarked at how well he looked. He was a loyal patron of local music events, coming to amateur concerts such as these, and also professional concerts which I occasionally promote in the village hall, always accompanied by his most loyal and tireless wife Marjorie. To her, and to his family, I can only say that I will miss Ronald greatly.

I last saw Ronald shortly before Christmas, when he came to the Broughton Choral Society concert, at which we were performing a short piece called The Dream, by Savourna. He was as charming as ever and everyone remarked at how well he looked. He was a loyal patron of local music events, coming to amateur concerts such as these, and also professional concerts which I occasionally promote in the village hall, always accompanied by his most loyal and tireless wife Marjorie. To her, and to his family, I can only say that I will miss Ronald greatly.

Footnote by David Nice: I can't claim to have known Ronald Stevenson anywhere near as well as Christopher did, but he left an indelible impression as a presence at the 1983 Aldeburgh Festival, where I was working as a Hesse Student. There was a mini-Grainger festival, in which Stevenson gave a recital at the Jubilee Hall, spinning our heads with Grainger's Rosenkavalier Ramble, amongst other oddities. And at the big Snape Maltings concert, where I heard for the first time - and, alas, never since under live circumstances - the amazing Tribute to Foster with rim-rubbed wineglasses as the music of the spheres, Stevenson was sitting behind us students. He tapped me on the shoulder after one piece and said, "Stravinsky, eat your heart out. Tell me he could ever have written a melody like that". Of course we didn't jump to agree with him, but I love it that he stood up so wholeheartedly for the power of original melody.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Add comment