Sotto Voce, Dominique Lévy | reviews, news & interviews

Sotto Voce, Dominique Lévy

Sotto Voce, Dominique Lévy

With seductive holes and nails hammered in aggressively, white is not as pure as it pretends

Sotto Voce is a collection of white paintings, sculptures and reliefs made by European, British and North and South American artists from the 1930s to 1970s. An accompanying book explains why this non-colour has appealed to so many artists in so many countries over such a long period of time.

At first, everything looks much the same – a collection of rather featureless white abstracts. But stick around and your eye quickly becomes attuned to the nuances in the work. Take Günther Uecker. Like many in the exhibition, the German artist chose to work in white as both an aesthetic choice and a declaration of intent.

Distancing himself from the horrors of World War Two and the values that allowed it to happen, he adopted white to signify belief in a new beginning full of optimism and hope. “I do not belong to the generation of the guilty,” he wrote, “but to the generation of the guilt heirs.” Purged of references to reality, the work can be enjoyed in and of itself – purely as a sensual experience – or can be seen as a tabula rasa embodying a spiritual purity unsullied by base human needs, instincts and desires.

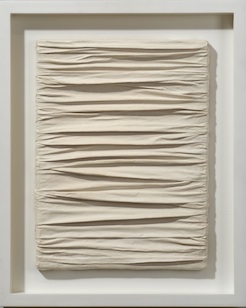

Some 40 years on, though, things have changed. We are less willing to be wooed by utopian dream(er)s, so the motivation for embracing white seems less important and similarities in intent less interesting than the amazing differences achieved with such a limited palette. (Pictured left: Piero Manzoni, Achrome, 1958).

Some 40 years on, though, things have changed. We are less willing to be wooed by utopian dream(er)s, so the motivation for embracing white seems less important and similarities in intent less interesting than the amazing differences achieved with such a limited palette. (Pictured left: Piero Manzoni, Achrome, 1958).

Uecker’s Untitled, 1967 is a neat grid of nails hammered at right angles into a square board. Everything is painted white, so the implied aggression of the act is muffled by uniformity, in much the same way that fresh snow unifies the view by suppressing differences. Shadows cast by the nails across the surface create patterns that change with the light and animate the piece, yet it remains fundamentally static.

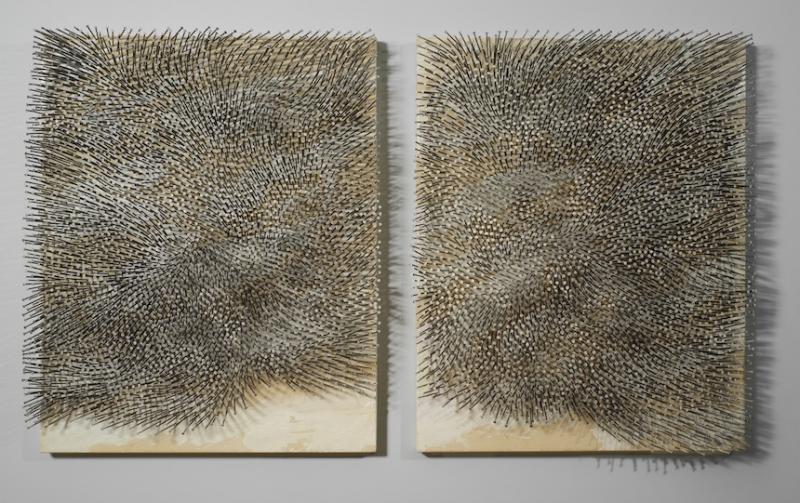

Wind, 2009, (main picture) on the other hand, is so dynamic it looks as though it might blow off the wall. Uecker has used larger, three-inch nails hammered in at different angles to achieve a semblance of motion. The heads of the nails are painted white but the stems are left dark, which makes the relief look as organic as a field of barley blowing in the wind. The presence of two panels rather than one creates an ongoing dialogue, while the shadows cast on the wall between them enliven this potentially inert space with spiky patterns. As a result everything seems to dance, spiral and spin.

Most of the exhibits would have been absolutely pristine when they were made. Over the years many have aged and acquired a patina of dirt or discoloration. It's a reminder that even the purest art exists in the real world and, like everything else, is subject to decay. Far from negating the work and its purpose, this realisation adds pathos and enriches one’s experience by introducing another layer of meaning.

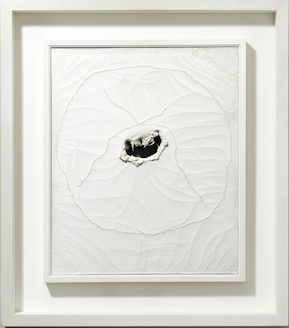

Lucio Fontana’s canvases were damaged at source, though. He attacked many with a knife, inflicting vertical slashes that puncture the surface to reveal the darkness hidden beneath. A blunt instrument has gouged a deep and very seductive wound at the heart of Concetto spaziale, 1964 (pictured right), which gapes open like a mouth inviting entry. Fontana has circled the gash with incised lines and inscribed his signature in the thick paint lathered like cream all over the canvas. From a distance, the ensemble reminds one of a pale flower with a dark centre; close to, one realises that the entire surface is patterned with fine cracks resembling the veins in a petal. How soon they appeared is a matter of speculation, but Fontana clearly anticipated them and enjoyed the juxtaposition of his incisions with these tiny fissures.

Lucio Fontana’s canvases were damaged at source, though. He attacked many with a knife, inflicting vertical slashes that puncture the surface to reveal the darkness hidden beneath. A blunt instrument has gouged a deep and very seductive wound at the heart of Concetto spaziale, 1964 (pictured right), which gapes open like a mouth inviting entry. Fontana has circled the gash with incised lines and inscribed his signature in the thick paint lathered like cream all over the canvas. From a distance, the ensemble reminds one of a pale flower with a dark centre; close to, one realises that the entire surface is patterned with fine cracks resembling the veins in a petal. How soon they appeared is a matter of speculation, but Fontana clearly anticipated them and enjoyed the juxtaposition of his incisions with these tiny fissures.

Fontana declared that he was “seeking to represent the void. My art is based”, he said, “on this purity, on this philosophy of nothing”. This makes it especially ironic that Concetto spaziale appears so unashamedly sensual. Not only is one’s attention focused on the lush paint surrounding the so-called void, but the wound itself seems deliberately fleshy and inviting.

Mira Schendel’s Untitled (XII), 1986 appears to make reference to Fontana’s slashes. Across the top of a rectangular slab, whose perfect white surface bears very faint pock marks as though it were skin, runs a black line resembling a knife wound. The introduction of this subtle illusion in a work that otherwise seems so nakedly honest adds a touch of humour that may not have been intended.

Untitled, 1974 by Italian minimalist, Ettore Spalletti is an exquisite mix of restraint and sensuality. A slab of creamy white impasto lies on a white board like a layer of shiny caramel coating a biscuit. The sides of the slab are straight, but the ends undulate as though to add an air of informality. Look carefully and three tiny cracks become visible in the impeccably smooth surface of this delicious object. I’m sure they are not intentional; the question, though, is whether one regards them as flaws that need to be retouched or as welcome reminders that the work has a history.

Artworks rarely turn out as the artist intended; and if one's goal is to embrace absolute purity, the discrepancy between aim and outcome is likely to be considerable. But as with the sensuality of Fontana’s canvases, the unintended qualities are often what makes a work most interesting or desirable. Because many of the artists in the exhibition were after perfection, Sotto Voce makes one especially aware that paintings and sculptures are material objects that change with time, rather than ideals that live in our heads.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment