Prom 16: Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic, Goetzel/Prom 17: Les Arts Florissants, Christie | reviews, news & interviews

Prom 16: Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic, Goetzel/Prom 17: Les Arts Florissants, Christie

Prom 16: Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic, Goetzel/Prom 17: Les Arts Florissants, Christie

Communication at the highest level in orchestral orientalia and Rameau motets

The sprightly tread of Handel’s Queen of Sheba, attended by two wonderful Turkish oboists, wove the most fragile of gold threads between full orchestral exotica and Rameau motets of infinite variety last night. Not that any more links need be found: it’s the addition of the late night events which turns the Proms into a real festival, not the mere concatenation of concerts you might find in the main orchestral season.

Pace the late Edward Said, orientalism no longer needs to be a dirty word, in music at least, now that orchestras like Istanbul’s mostly Turkish forces can reclaim a western, or at least a western-trained, appropriation of eastern promise. The Borusan team has already proved its mettle with discs of characteristic adventurousness, most recently a hybrid showcasing one of the very best performances of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade I’ve ever heard, complete with brief qanun (Turkish zither) and oud (lute) interludes which really work.

Before that, admiration had to be limited to Respighi's shot-silk orchestration and the Borusan woodwinds’ perfect and free execution of the many drifting arabesques. Holst’s Beni Mora isn’t stacked with memorable ideas either, rather overplaying the oriental intervals of limited invention in its first two dances, but the Algerian motif of the concluding processional becomes a haunting ostinato to an Arabic equivalent of Debussy’s "Fêtes", with a similar interior quality.

The Handel and Mozart’s Overture to Die Entführung aus dem Serail with its Turkish janissary-band percussion showed us how adaptable and sprightly the Istanbul orchestra can be. It won its right to play a rhythmically interesting but - again - thematically insubstantial encore by pioneering Turkish composer Ulvi Cemal Erkin, the "dance rhapsody" Köçekçe of 1942, introduced with spirit and a very clear, unamplified voice by born motivator Goetzel. Brave and enterprising of them, too, to include the world premiere of a BBC Commission, Gabriel Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto, composed with that excellent violinist Daniel Hope in mind. The territory, we’re told, is the trenches of World War One, but the mud got in the way of any mobility.

Immortality seemed more certain with Rameau’s relatively early motets. He was 30 when he began them, 50 when he embarked on the stunningly original operas which truly made his name. No question, the Rameau quirkiness and lavishly original use of limited instrumental forces only fully bursts upon us in the third of the late night Prom’s official sequence, In convertando Dominus, and the reason is clear: Rameau overhauled it, to what extent we don’t know as the earlier score is lost, in 1751, well into his operatic mastery.

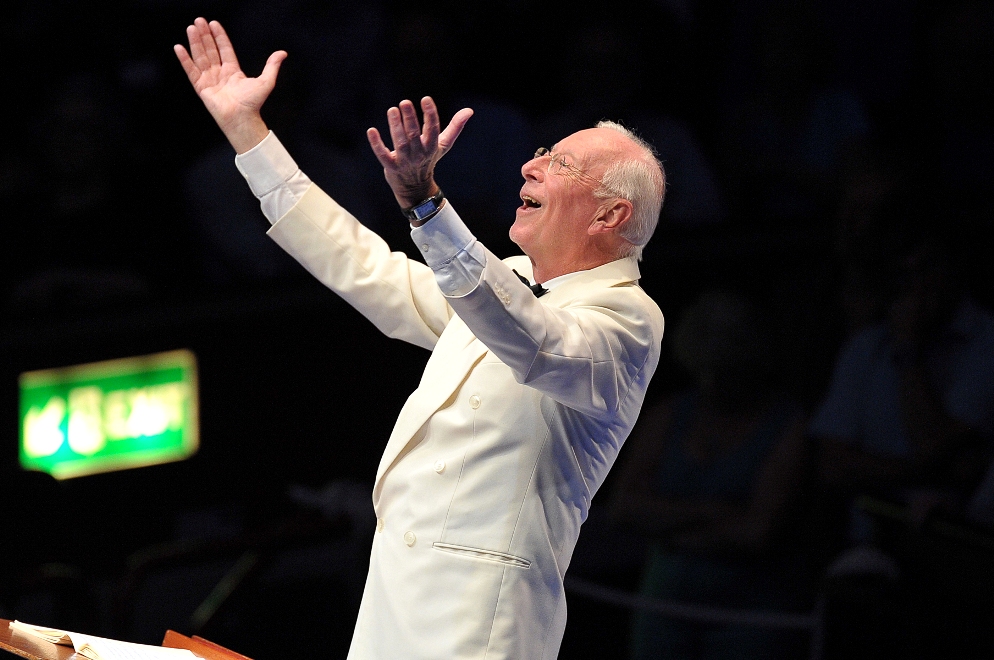

Not that invention is lacking in the less ornate predecessors we heard. Rachel Redmond, a more than promising young soprano of blithe presence and warm upper register which made the most of the Albert Hall surround-sound, launched Quam dilecta tabernacula in intimate dialogue with the two flutes. Their presence was made clear by further illustration: these are the sparrow and the turtledove who finds a nest for its young in the Lord’s dwelling place. More distinctive singing from the other members of Les Arts Florissant’s solo team was crowned by high tenor Reinoud Van Mechelen (pictured above). He ornamented as stylishly as the collective instrumental and vocal forces, voice types dispersed around the line-up for greater fluidity.

Then we had proper Rameau anniversary solemnity: the transcendentally grave Act 1 chorus from Castor et Pollux reworked as a Kyrie for his funeral in 1764, lightened by the Elysian fields of “O tendre amour”, again religiously recast, as “O fons vivus caritas". And how could a Rameau homage not end with a virtuoso storm scene? Only this wasn’t one of the famous examples from his operas but another coup de foudre from de Mondonville, the tempest movement from his second grand motet Dominus regnavit, outstripping the relatively tame nature-shudders in the first Rameau offering of the evening. Such generosity, such perfection of execution: thank you, Mr Christie.

- Catch both Proms on the BBC Radio iPlayer for the next month - Prom 16 here and Prom 17 here

- Turkish Prom filmed for broadcast on BBC Four on 31 August at 7pm

- David Nice's blog on Christie's Rameau at Glyndebourne

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Add comment