theartsdesk in Basel: More than Minimalism | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Basel: More than Minimalism

theartsdesk in Basel: More than Minimalism

In a beautiful and cultured city, 20th-century music and art shine (Glass excepted)

In a near-perfect, outward-looking Swiss city sharing borders with France and Germany, on a series of cloudless April days that felt more like balmy June than capricious April, anything seemed possible.

The Glass conversion, though, didn’t happen, not that the static American’s millions of fans – some of whom will find their way to the Cadogan Hall this week – could care less. Glass’s Plutonian Ode, his Sixth Symphony based on a gabby text by Allen Ginsberg which was never going to fit well to music, turned out, for all its quicker changes of mood, to be a slab of mind-blowing banality. Its patchwork technique, if so it could be called, is anti-symphonic, its harmonies unevolved from the early days, with the exception of several bitonal flashes and good endings to first and second movements, its orchestration breathtakingly amateurish, unless you find side-drum rattling along with chugging strings attractive – and pity the poor under-involved woodwind.

Unlikely as it may seem, Basel was the birthplace of Israel

Pity even more the singer stuck with ungainly text-setting in an uncomfortable middle to upper range. Dramatic soprano Karen Robertson (pictured below right with Davies and the orchestra by Jean-Francois Taillard), who’s exchanged her native Australia for Austria as house singer in Davies’s Landestheater Linz company, coped masterfully, but her real talents lay untapped: I hope I get to hear her as Elektra and Brünnhilde, obvious next steps for her.

That I didn’t care for the work is rather beside the point bearing in mind Davies’ plan in this mini-festival: to showcase some of the key works of composers who began in the Minimalist school which is now part of history, and then did one of three things: got stuck there, like Glass, quickly took wing from its samey savannah – as Adams and for that matter Reich absolutely did – or came to a special form of it from more complicated beginnings, as in Pärt’s case, like an artist skilled in naturalistic technique who chooses the most simple-seeming abstraction. Michael Nyman merely moved sideways and I can’t help feeling there was less to his 1995 Concerto for trombone and orchestra than met the ear; but a born communicator, the brilliant Basel-based trombonist Mike Svoboda, sold its playfulness to me and chimed with a happy, summer-holiday mood. Besides, the concerto sat entertainingly next to Pärt’s austerity, where percussion forms until the climax an ominous subtext to the strings’ prayers; in the Nyman the kitchen sink eventually runs riot.

That I didn’t care for the work is rather beside the point bearing in mind Davies’ plan in this mini-festival: to showcase some of the key works of composers who began in the Minimalist school which is now part of history, and then did one of three things: got stuck there, like Glass, quickly took wing from its samey savannah – as Adams and for that matter Reich absolutely did – or came to a special form of it from more complicated beginnings, as in Pärt’s case, like an artist skilled in naturalistic technique who chooses the most simple-seeming abstraction. Michael Nyman merely moved sideways and I can’t help feeling there was less to his 1995 Concerto for trombone and orchestra than met the ear; but a born communicator, the brilliant Basel-based trombonist Mike Svoboda, sold its playfulness to me and chimed with a happy, summer-holiday mood. Besides, the concerto sat entertainingly next to Pärt’s austerity, where percussion forms until the climax an ominous subtext to the strings’ prayers; in the Nyman the kitchen sink eventually runs riot.

Best of all, undoubtedly, was the sleek, unforced and unerringly paced performance of Adams’ symphony in all but name, Harmonielehre, with its sense of moving through space. Davies never hit the spectacular opening movement’s takeoff from San Francisco bay too hard, leaving us energy to absorb the Mahlerian dissonances of the second, “The Anfortas [sic] Wound”. An orchestra of this size in the ideal shoebox acoustic of Basel’s Stadt-Casino looked as if it might be too large for the venue, but balances were immaculate and when the lower brass and bass drum came into their own, they shook the body. It will be interesting to hear how the Cadogan Hall accommodates these impressive forces.

Built in 1876, the Stadt-Casino’s 1500-seater auditorium accommodated an extraordinary event 21 years later when Theodor Herzl presided over the First Zionist International Conference. So, unlikely as it may seem, Basel was the birthplace of Israel. But then it has always been an enlightened centre of learning and culture. Erasmus of Rotterdam came here, encouraged by the bookishness born of the city’s fine paper factory (he had close ties with the printer Johann Froben, in whose home he died in 1536).

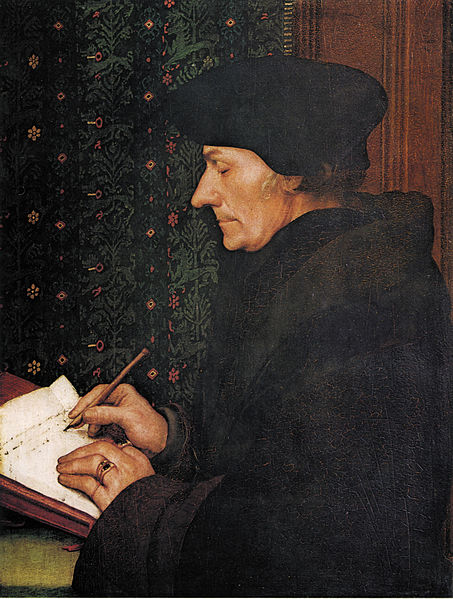

Basel’s most celebrated artist, Hans Holbein the Younger, painted Erasmus several times; two of the finest portraits are in the extraordinary collection of the Kunstmuseum, overdue an expansion – one from 1523 (pictured left), the other from 11 years later. Here you’ll find no works of the Italian Renaissance, but the northern school is extraordinarily well served thanks partly to the city's 1661 purchase of Basel lawyer Basilius Amerbach's great collection – a civic tradition here, just as it was an aristocratic one with princes elsewhere - with a room of religious paintings by Konrad Witz rivalling the 35 Holbeins.

Basel’s most celebrated artist, Hans Holbein the Younger, painted Erasmus several times; two of the finest portraits are in the extraordinary collection of the Kunstmuseum, overdue an expansion – one from 1523 (pictured left), the other from 11 years later. Here you’ll find no works of the Italian Renaissance, but the northern school is extraordinarily well served thanks partly to the city's 1661 purchase of Basel lawyer Basilius Amerbach's great collection – a civic tradition here, just as it was an aristocratic one with princes elsewhere - with a room of religious paintings by Konrad Witz rivalling the 35 Holbeins.

Erasmus was buried in Basel's Minster, a mark of high respect from Protestants. The sandstone quasi-Cathedral with its beautiful tiled roof towers high over the banks of the Rhine, a clean stretch where swimmers in summer navigate their way from one point to another with their clothes in a newly traditional Basel waterproof bag shaped like a fish. Beneath the Minster a ferry powered entirely by the river's current has been in operation since 1845, when there was only one main bridge.

The buildings of Basel’s many rich merchants cluster around or near the Cathedral. Here you’ll find the priceless manuscript collection of that great Basel commissioner and founder of the city's Chamber Orchestra Paul Sacher, responsible for masterpieces by Stravinsky, Bartók, Strauss, Hindemith, Boulez and Birtwistle, among others: time and appointment were needed for that, so I hope to return. But the most remarkable assemblage of masterworks is a quick tram journey out of the city centre in Riehen just on the German border, where Ernst and Hildy Beyeler not only gathered one of the finest selections of 20th-century masterpieces in the world but also had a building designed by Renzo Piano to do them better justice than any comparable gallery I’ve ever seen.

You float, rather than walk, through the spacious rooms of the single-storey Fondation Beyeler. Piano's architecture serves the pictures and sculptures instead of upstaging them, with the contribution of natural light from the glass ceiling working its own special magic. Like the Minimalist scores in Davies’s special selection, the works on display have so much space to breathe and glow, from a giant Monet canvas to two stupendous Anselm Kiefer epics hanging in the northernmost room alongside African sculptures. Giacometti’s figures seem like passing visitors in the preceding room (pictured right), which in a sense they are: the collection is never entirely on display, and moves from one half of the building to the other while exhibitions are being set up so that the Foundation never has to be closed.

You float, rather than walk, through the spacious rooms of the single-storey Fondation Beyeler. Piano's architecture serves the pictures and sculptures instead of upstaging them, with the contribution of natural light from the glass ceiling working its own special magic. Like the Minimalist scores in Davies’s special selection, the works on display have so much space to breathe and glow, from a giant Monet canvas to two stupendous Anselm Kiefer epics hanging in the northernmost room alongside African sculptures. Giacometti’s figures seem like passing visitors in the preceding room (pictured right), which in a sense they are: the collection is never entirely on display, and moves from one half of the building to the other while exhibitions are being set up so that the Foundation never has to be closed.

At present a Rothko "chapel" stands at the heart of the spiritual adventure, while a yellow square in a Mondrian painting reflects the field of rape outside the window. The Beyeler's Monet Waterlilies would normally complement the lily pond beyond. But in that room instead, at the moment, we have the luminous deep blues and golds of Odilon Redon’s pastels in part of an exhibition space which lets these visionary masterpieces hover in space. It’s worth heading out to Basel before mid-May, when the Redon spectacular ends, to see this model of what an exhibition can look like; even the Matisse cut-outs at Tate Modern, among which are two significant loans from the Fondation Beyeler (one of the four blue nudes and a giant Acanthus picture), can’t boast as beautiful a hanging space. From the haunted phantasmagoria of the "‘noirs" – charcoal drawings or lithographs – which mark slow developer Redon’s first phase, you move to the incandescent pastels. Many of the masterpieces are here, chiefly Buddha and The Chariot of Apollo of 1910 (pictured below © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski), a sky-soaring no less visionary than Adams's in Harmonielehre, both from the Musée d’Orsay - though there are significant loans from private collections.

And for all this there’s a relaxed attitude to museum curating which means you never feel hassled, distracted by fellow spectators, merchandise or the tea shop (kept discreet further along the lovely garden), only benignly watched by the room attendants, one of whom for some reason gave me a pencil as I was writing in my notebook. It’s part of the Basel easy-going quality, its Gemütlichkeit, as distinct from ever so slightly prissier Zurich, which I noticed in the concert-hall attenders of all ages and in a very much loved and used church, the Leonhardskirche, where the stage was set in the chancel for a (wholly secular) play. A veteran parishioner told me how the students from the distinguished Hochschule für Musik – where Svoboda is a professor – drop in to practise the organ when they feel like it, and lifted a grill in the vestry to take me down to see the Romanesque baptistery. I might be slightly dizzied by the heady airs of a deceptive early summer atmosphere, but this looks like a city which I could live in and love.

And for all this there’s a relaxed attitude to museum curating which means you never feel hassled, distracted by fellow spectators, merchandise or the tea shop (kept discreet further along the lovely garden), only benignly watched by the room attendants, one of whom for some reason gave me a pencil as I was writing in my notebook. It’s part of the Basel easy-going quality, its Gemütlichkeit, as distinct from ever so slightly prissier Zurich, which I noticed in the concert-hall attenders of all ages and in a very much loved and used church, the Leonhardskirche, where the stage was set in the chancel for a (wholly secular) play. A veteran parishioner told me how the students from the distinguished Hochschule für Musik – where Svoboda is a professor – drop in to practise the organ when they feel like it, and lifted a grill in the vestry to take me down to see the Romanesque baptistery. I might be slightly dizzied by the heady airs of a deceptive early summer atmosphere, but this looks like a city which I could live in and love.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment