Chroma/ The Human Seasons/ The Rite of Spring, The Royal Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Chroma/ The Human Seasons/ The Rite of Spring, The Royal Ballet

Chroma/ The Human Seasons/ The Rite of Spring, The Royal Ballet

A modern classic and two relative newcomers

This triple bill is of works commissioned for the Royal Ballet: Kenneth MacMillan’s The Rite of Spring was first performed in 1962, Wayne McGregor’s Chroma had its debut in 2006 while this is the world premiere of David Dawson’s first ballet for Covent Garden, The Human Seasons.

McGregor’s Chroma (pictured below right) is an oddly pallid affair, given that its name refers to the saturation of pure colour, free from admixtures of white or black. The set by minimalist architect John Pawson is characteristically sparse. Dancers step onto the stage through a rectangular opening; clever lighting transforms the space framed behind into a solid, a void or a liminal zone where dancers can linger in the twilight. Once over the threshold, they are bathed in bright light that emphasises their pale skin tones and, dressed only in pastel vests and knickers, makes them seem disconcertingly vulnerable .

The piece is structured like a record album, with tracks by Joby Talbot and Jack White III of American rock duo, The White Stripes. The opening music which could be the soundtrack of a James Bond film, is strangely at odds with the sterile convulsions it accompanies. The straight, linear articulations of McGregor’s choreography make the dancers appear awkwardly angular – all sharp joints and spidery limbs. I began to imagine them as a group of wooden lay figures left alone in the studio by an artist; like Petrushka, they have come to life but fail to attain full-blooded vitality. For despite their tremendous agility, these superb dancers appear like sexless cyphers drained of all passion.

The piece is structured like a record album, with tracks by Joby Talbot and Jack White III of American rock duo, The White Stripes. The opening music which could be the soundtrack of a James Bond film, is strangely at odds with the sterile convulsions it accompanies. The straight, linear articulations of McGregor’s choreography make the dancers appear awkwardly angular – all sharp joints and spidery limbs. I began to imagine them as a group of wooden lay figures left alone in the studio by an artist; like Petrushka, they have come to life but fail to attain full-blooded vitality. For despite their tremendous agility, these superb dancers appear like sexless cyphers drained of all passion.

Inspired by John Keats’ eponymous poem, David Dawson’s The Human Seasons is far more lyrical. Keats likens the aging of a human life to the seasons of the year, yet Dawson’s ballet contains no readily discernible changes in temperature, mood or tempo. The dancers move as fast and as fluently in old age as they do in youth; the piece ends as it begins, in fact, with a triumphal tableau of four men valiantly holding aloft four reclining women.

A man pushes his partner forwards like a lawn mower, her open legs as stiff as scissor blades

With its resemblance to cardboard packaging, Eno Henze’s set looks distinctly unpromising. But at judicious moments, lines of bright light zip across the black, grey and brown rectangles creating vertical or diagonal accents that transform the dull box into a dynamic abstraction reminiscent of a Barnett Newman painting enhanced by Dan Flavin’s light sculptures.

Against this ever-changing composition the dancers continuously weave fluid arabesques. Beautifully offset by Yumiko Takeshima’s costumes which resemble neat swimwear, the sinuous undulations of the women reminded me of Cranach’s painting of the scantily clad Three Graces with their sensuous curves. There’s rather too much wafting and tippy-toeing around, but this is interrupted by some highly original sliding and shoving; a man swings his partner sideways or pushes her forwards like a lawn mower, her open legs as stiff as scissor blades, her feet sliding over the floor.

The most interesting section is like a genteel gang rape; six men pass a woman from one to another before collaborating in dragging her about, hoisting her up and tossing her from group to group; throughout this manhandling she remains calm, collected and perfectly poised.

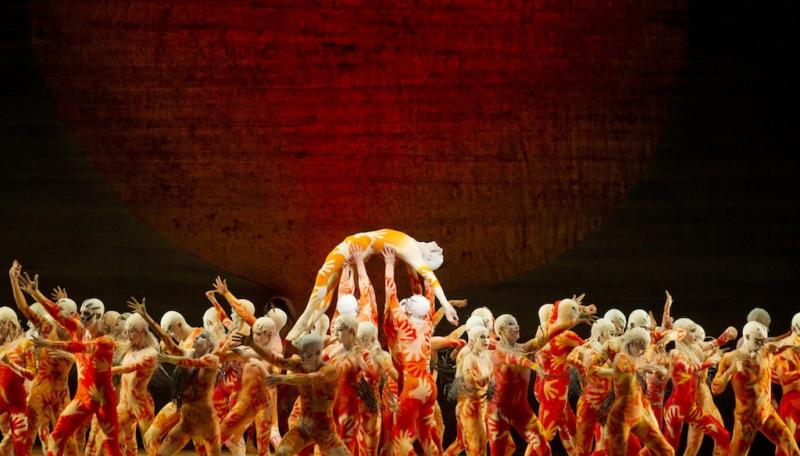

It's just over 50 years since Kenneth MacMillan’s The Rite of Spring (pictured above) was first performed at the Royal Opera House and 100 years since Nijinsky’s choreography caused a riot when the ballet was first performed in Paris, in May 1913. On that famous occasion, the uproar drowned out Stravinsky’s music, but this time round you can hear every note – from the eerie opening bassoon solo to the chugging rhythms churning in the strings and the declamatory outbursts of the brass. Then there’s the swish-swish of the dancers feet as they shuffle about in unison adding a sinister, whispering undertow to the murderous proceedings.

It's just over 50 years since Kenneth MacMillan’s The Rite of Spring (pictured above) was first performed at the Royal Opera House and 100 years since Nijinsky’s choreography caused a riot when the ballet was first performed in Paris, in May 1913. On that famous occasion, the uproar drowned out Stravinsky’s music, but this time round you can hear every note – from the eerie opening bassoon solo to the chugging rhythms churning in the strings and the declamatory outbursts of the brass. Then there’s the swish-swish of the dancers feet as they shuffle about in unison adding a sinister, whispering undertow to the murderous proceedings.

For this is a story of sacrifice – of a young girl, chosen by the elders to dance herself to death for the renewal of the tribe. Designed by Australian painter Sidney Nolan, the handprints often left by aboriginal peoples to mark their presence have migrated from the rock face to the unitards worn by the 43 dancers. With their faces uniformly painted white, these primal beings move in packs reminiscent of football crowds or onlookers at a wrestling match. Whether jumping or hopping like frogs, stomping on splayed legs, huddling in clumps with arms raised in salute or slithering on their bellies like synchronised swimmers, they swarm with one mind as though driven by a common will – the embodiment of the collective unconscious.

The most chilling moment of the ritual comes when the sacrificial victim is handed back over the heads of the crowd before being encircled and raised aloft like a totem pole. Last night, Zenaida Yanowsky danced the role of the Chosen One with a lightness and balletic grace that sets her apart from her fellow tribespeople who stand in a gaggle behind her egging her on. Her death therefore seems less like the result of pounding exhaustion than of ecstatic submission to Fate. This makes her dance beautiful to watch, but her end somewhat anti-climactic; a more brutal martyrdom would have felt more appropriate.

- The Royal Ballet performs Chroma, The Human Seasons and The Rite of Spring at the Royal Opera House until 23 November

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Comments

Looks like Ric Cervera in the

Chroma is 'oddly pallid'.