Madam Butterfly, English National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Madam Butterfly, English National Opera

Madam Butterfly, English National Opera

The late Anthony Minghella's ice-cool staging of Puccini's ardent masterpiece returns to ENO

When the going gets tough, wheel out a crowd-pleaser. Even by its own volatile standards English National Opera has had a poor start to its autumn season, with productions of Fidelio and Die Fledermaus that seem destined to join the company’s ever-growing chamber of unrevivable horrors. ENO’s cash-strapped board must therefore be lighting another candle to the late Anthony Minghella, whose glacially delicate Madam Butterfly is always good for an outing.

It’s an award-winning favourite that was mounted with extraordinary sensitivity by a director better known for his film work. Cards on the table: it’s a staging I find infuriating, yet despite myself I relished the chance to wallow again in its gorgeousness. If you haven’t seen it before, don’t let me put you off. A feast for the eye is guaranteed.

The story of Cio-Cio San is a heartbreaking tale of devotion, rejection and despair

The visual language is a paean to the ritualised beauty of traditional Japanese art – a decision that would be ideal were it not for the contradictory mood of Puccini’s score, which drips with Italian fervour. The story of Cio-Cio San, a young geisha whose night of pleasure with US Naval Lieutenant Pinkerton means so much more to her than it does to him, is a heartbreaking tale of devotion, rejection and despair. Inevitably, though, in directing this latest revival Sarah Tipple has stayed faithful to Minghella’s blueprint – which means that scenes like the erotic Act One love duet still flounder. Although ravishing to behold with its sea of hand-held lanterns and scattered rose petals, the tenor of idealised love versus rampant sexuality is completely neutralised by a wash of ostentatious, Kabuki-scented prettiness.

The Italian conductor Gianluca Marcianò made a distinguished house début, shaping Puccini’s rich, cod-exotic orchestrations with exemplary balance and securing ensemble work from the ENO Chorus and Orchestra that was at once precise and relaxed. He was wholly attentive to the needs of his solo singers; it was certainly not his fault that Timothy Richards’s smallish voice failed to cut past the footlights and caused his Pinkerton to make such a disappointingly pale impression.

With far richer vocal colours and a heartbreaking engagement with her character, the Russian-American soprano Dina Kuznetsova was a revelation as Cio-Cio San. Her full-blooded timbre, darker of hue than we usually hear in this girlish role, lent a mournful flavour to her performance and made for an exceptional partnership with mezzo Pamela Helen Stephen’s wonderfully sung, fully-realised Suzuki. The silent collapse of Stephen’s face on learning the truth about Pinkerton was reactive acting of the highest order.

Cio-Cio San's wedding guests in Act One of ENO's Madam Butterfly

It is always a pleasure to see baritone George von Bergen’s name on a roster: he is a very fine operatic actor. His bumbling Sharpless, the bluff but baffled American Consul, was a characteristically well-delineated creation that more than made up for an atypically unfocused vocal performance. Only an off-night I hope. There were strong cameos from Alun Rhys-Jenkins as the marriage-broker Goro, Mark Richardson as the intimidating Bonze, Alexander Robin Baker as Prince Yamadori (Butterfly’s would-be suitor) and, especially, from a clear-voiced Catherine Young as poor Kate Pinkerton.

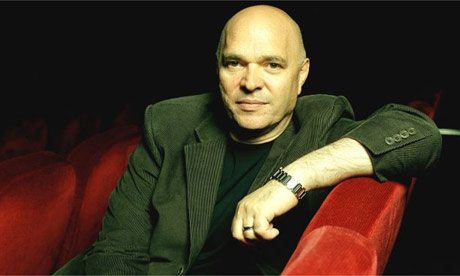

The fifth principal in Madam Butterfly is Sorrow, Cio-Cio San’s son – a challenging part for a young child to carry off successfully, albeit one that was managed with moving aplomb by a very small boy at Opera Holland Park earlier this year. In 2005, when this ENO production first appeared, Minghella (pictured below) famously rejected the human option in favour of the fabulous puppetry of Blind Summit – and four revivals in it still doesn’t work.

The problem is simple and should have been obvious to such a gifted director: however ingenious the manipulation by three skilled Bunraku puppeteers, it only serves to draw the audience away from an emotional connection with Pinkerton's innocent offspring and into a mood of detached admiration for the sheer cleverness of it all. The portrayal has a certain wooden charm but it is no substitute for a flesh-and-blood child whose vulnerability might awaken the spectator’s protective instincts. To watch human hands bring a telescope to a puppet’s eye is distracting, not affecting.

The problem is simple and should have been obvious to such a gifted director: however ingenious the manipulation by three skilled Bunraku puppeteers, it only serves to draw the audience away from an emotional connection with Pinkerton's innocent offspring and into a mood of detached admiration for the sheer cleverness of it all. The portrayal has a certain wooden charm but it is no substitute for a flesh-and-blood child whose vulnerability might awaken the spectator’s protective instincts. To watch human hands bring a telescope to a puppet’s eye is distracting, not affecting.

The real hero of Minghella’s Madam Butterfly is Peter Mumford, who is responsible for the ingenious lighting. It is impossible to overstate Mumford’s role in defining the production: his work breathes life into Michael Levine’s opulently spare designs and transforms an almost bare, almost flat rectangular stage into an epic world. The penumbral lighting of motionless singers in Act One (see top of page) turned them for one extraordinary moment into an array of icons, the variegated satin of their costumes made to resemble the painted models of Cio-Cio San’s ancestors. It was just one dazzling effect in a production that is bathed in beauty from first to last. If only it were more than skin-deep.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Comments

What set me in a rage the one

Yes David, it's still there -