Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, British Museum

Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, British Museum

A procession of extraordinary images, often ribald, occasionally hilarious, and staggering beautiful

Sex please, we are Japanese. This astonishing collection of about 170 paintings, prints and illustrated books from 300 years of Japanese art, known as “shunga” or spring pictures, come in part from the culture of the “floating world” (ukiyo-e) mostly located in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), from the mid 17th- to mid-19th centuries.

But shunga go beyond the world of paid-for pleasure, of courtesans and actors, of that world of pleasure that was allowed, as so many other worlds weren’t in the strict and hierarchical society of Japan. (Ordinary people were not allowed to participate for example in politics, and free speech was literally unheard-of.) These images were also talismans for samurai, the great warrior caste, and could be used as instruction books for respectable brides-to-be, and for ordinary couples of the mercantile classes.

Although the artists were all men, women are almost invariably not only portrayed sympathetically, but as though they are definitely enjoying themselves; they are neither passive nor victims, and the facial expressions are languorous, even ecstatic.

The British Museum was gifted a substantial collection in 1865 which was then secreted away for decades in a category called "Secretum". A handful have been included in exhibitions of Japanese art held at the BM in the past several decades, including all shunga by the master artist Utamaro, the artist of the Poem of the Pillow (see main picture). This, though, is the first exhibition to concentrate exclusively on shunga, and it calls on public and private collections to amplify the substantial holdings in the BM, one of the best outside Japan.

The British Museum was gifted a substantial collection in 1865 which was then secreted away for decades in a category called "Secretum". A handful have been included in exhibitions of Japanese art held at the BM in the past several decades, including all shunga by the master artist Utamaro, the artist of the Poem of the Pillow (see main picture). This, though, is the first exhibition to concentrate exclusively on shunga, and it calls on public and private collections to amplify the substantial holdings in the BM, one of the best outside Japan.

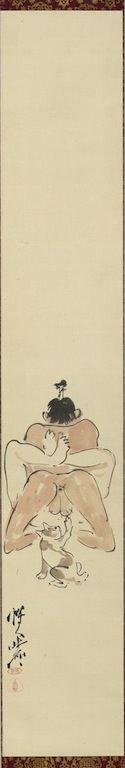

And the genre has survived. It was officially forbidden from 1722 but remained intact, indeed expanded into glorious and relatively inexpensive woodblock prints, with the authorities turning a blind eye to the activities of private printing presses for private consumption. It was an industry. Thousands upon thousands of prints were published, and several outstanding masters – Hokusai, Utamaro, Moronobu among them – included outstanding shunga prints among their oeuvre. Oddly, the time shunga was totally and effectively forbidden was the 20th century, from the Russo-Japanese war to 1989: Japan did not want the West to get ideas about Japan’s sexual permissiveness. (Pictured right: Kawanabe Kyosai, One of Three comic shunga paintings (detail), c.1871-89; © Israel Goldman Collection)

The images from the beautiful and expensive (lots of gold) early paintings to the woodblock prints, which often have illuminating and ribald commentary, and annotated illustrated books, are an eye-popping amalgam of how to do it, though attempting a few of the examples for the less limber would surely lead to a visit to accident and emergency.

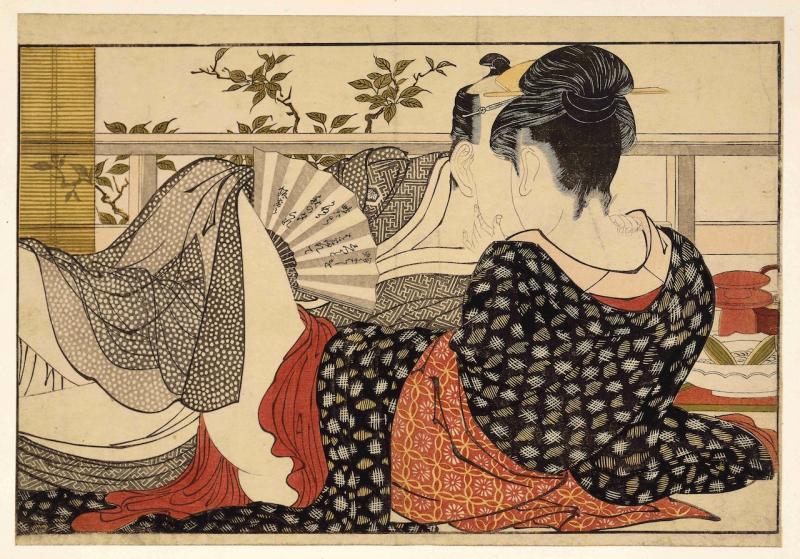

Many of the prints are a curious combination of differing and contrasting representations, often within the same image, both beguiling and appealing. There are exceptionally detailed, brilliantly colourful and marvellously expressive flowing textiles in glorious patterns, partly covering the bodies of men and women (and occasionally men with men, randy monks among the specialities). These textiles are sometimes even textured with a kind of hand stencil. The semi-clothed bodies are subtly rendered, their expressive movements hinted at by the flow of their robes. And they seem as numerous as the wholly naked.

The bodies themselves and the faces are the exact colour of the ivory-tinted paper of the prints. They are outlined in black, in sinuous lines in an uncanny pre-echo to Western eyes of the best of Matisse. There is no modulated colour in the portrayal of human bodies; even nipples are simply circles of ivory white outlined in black. The outlines are completely convincing, but there are also heavily exaggerated details: riots of curly pubic hair for both sexes, though there is not a hair out of place in the elaborate hairdos of both men and women (in spite of all that energetic activity).

The only overall hairy bodies belong to men imposing intercourse, so obviously the hairy body was thought to denote unpleasantness. Even more exaggerated are the genitalia of both men and women, and there is a riotous sequence from the 17th century of a penis-measuring event in which the members being measured must be several feet long. The female is also paid lavish attention: one 19th-century artist’s signature is even in the shape of a vulva.

In the couplings, and groups, every orifice available for lovemaking except perhaps the ears, which never seem involved in the general carry-on, is given careful detailed attention. Men literally handle the female genitalia with scrupulous attentiveness, and female secretions were much prized. One surprise is Hokusai’s ecstatic lady diver being serviced by two octopi under water; she was undoubtedly breathless for several reasons.

The detailed captions are an invaluable help in figuring out what is going on

Not only are there various permutations of group sex, there are various layers of social attachment too: geishas, courtesans, prostitutes are depicted gracefully plying their trade, as well as married couples, lovers and adulterers (although adultery was officially censured) - and many a coupling has a number of observers clustered round.

There is a tiny section showing the explicit influence of shunga on artists such as Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec and Aubrey Beardsley, who were all collectors themselves. John Singer Sargent, about whose sexual and emotional attachments nothing has been convincingly documented, was another, and some of his collection is at the British Museum.

Here every picture does indeed have a story, and the detailed captions are an invaluable help in figuring out what is going on, which is not always as clear as the sex manual connotations of some shunga might suggest. The whole exhibition acts as a crash course in certain aspects of Japanese culture and history, still mysterious to the West, and as an explicit study of sexual mores in Japan which was different and more overt than any other Asian country. It is a procession of extraordinary images, often ribald, occasionally intentionally hilarious, and at times staggeringly beautiful. Take your time; you will need it.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment