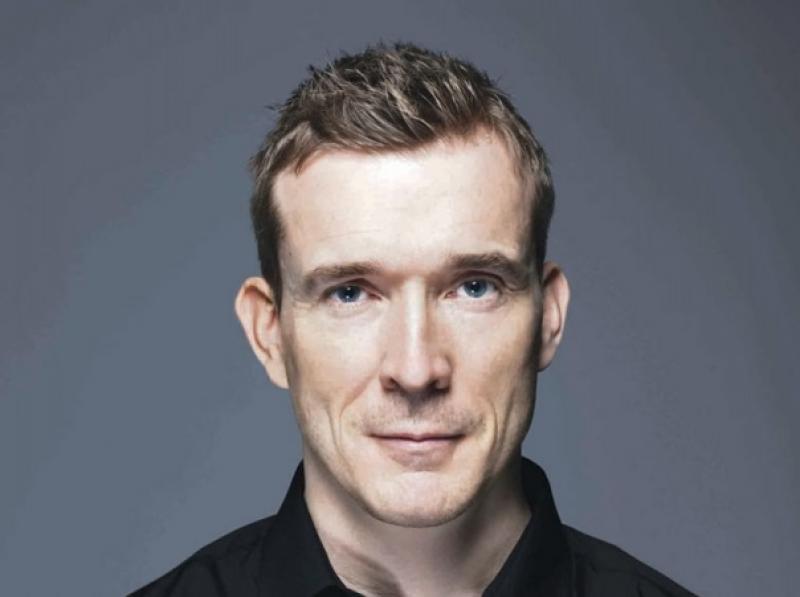

10 Questions for Writer David Mitchell | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Writer David Mitchell

10 Questions for Writer David Mitchell

The author of 'Cloud Atlas' has turned to modern opera

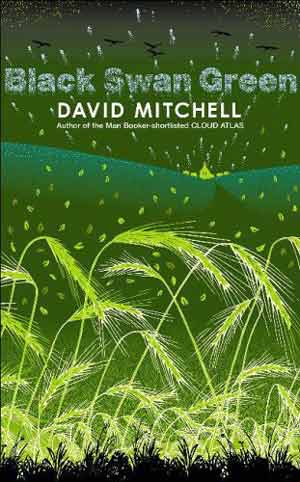

“If you show someone something you’ve written, you give them a sharpened stake, lie down in your coffin and say, ‘When you’re ready.’” The words belong to Jason Taylor, the stammering 13-year-old poet protagonist of David Mitchell's novel Black Swan Green. But they will do for any artist presenting fresh work. Mitchell is going through an extracurricular phase of presenting fresh work to a different kind of audience.

You never know what you’re going to get with Mitchell. Ghostwritten, his 1999 debut, commuted between genres and continents. He followed it up with the equally impressive but largely unrelated number9dream (2001), in which he dared to depict contemporary Japan through the eyes of a Japanese protagonist (his wife is Japanese, and he did live there before moving in 2004 to West Cork). Then came Cloud Atlas (2004), a compendious time-travelling globe-trotter of a novel which begins and ends in the Pacific of the early 19th century and between times leaps forwards via the present day towards a distant apocalyptic future. Black Swan Green (2007) is his barely disguised roman à clef set in the Worcestershire village in which the author grew up. His most recent novel, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (2011), returned to 18th century Japan.

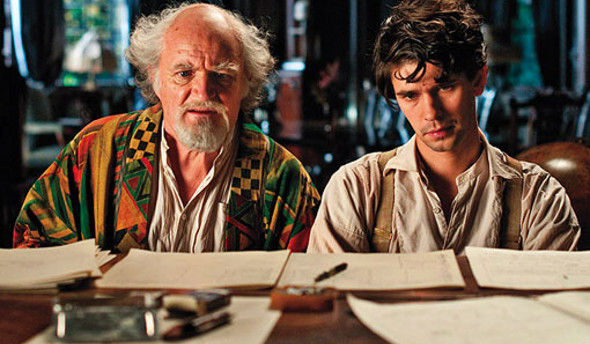

Anyone who has read or seen Cloud Atlas will know that the world of composition is not alien to Mitchell. One of the novel’s segments features the relationship between a crusty old English modernist composer called Vyvyan Ayrs and his pushy young amanuensis Robert Frobisher (these sections, set in Belgium in the book, were transposed to Scotland for the film). Mitchell was fond enough of their memory to lift Ayrs’s ravishing daughter Eva van Crommelynck out of Bruges and plant her half a century later in the Worcestershire of Black Swan Green, where she advises Mitchell’s young alter ego, the budding poet Jason Taylor, on telling the truth in art.

Anyone who has read or seen Cloud Atlas will know that the world of composition is not alien to Mitchell. One of the novel’s segments features the relationship between a crusty old English modernist composer called Vyvyan Ayrs and his pushy young amanuensis Robert Frobisher (these sections, set in Belgium in the book, were transposed to Scotland for the film). Mitchell was fond enough of their memory to lift Ayrs’s ravishing daughter Eva van Crommelynck out of Bruges and plant her half a century later in the Worcestershire of Black Swan Green, where she advises Mitchell’s young alter ego, the budding poet Jason Taylor, on telling the truth in art.

As he explains to theartsdesk, it was Ayrs and Frobisher who indirectly secured him his first operatic commission, Wake, written with the composer Klaas de Vries and premiered by the Dutch National Reisopera in 2010. Sunken Garden is another Dutch collaboration, this time with van der Aa, the product of a novel he had been working on, and may yet complete.

JASPER REES: How does a successful Booker-nominated novelist get involved in writing an opera?

DAVID MITCHELL: Just from one thing leading to another. Stage one was writing Cloud Atlas and having a composer character. A real-life composer Klaas de Vries, an elder statesman of Dutch music, read it and assumed I knew my musicological stuff and came to meet me after an event and over a couple of meetings talked me into writing the libretto for a very particular commission he had received, an opera to commemorate an explosion in a firework factory in 2007, which blew up a sizeable quarter of the town of Enschede. It was a major miracle that hundreds of people weren’t killed and only 10. I worked on that with Klaas and then when that was being staged Michel van der Aa saw that and a few weeks later sent an email saying, "If you fancy ever having a meet-up and a chat about a possible blank-slate collaboration where there are no preconditions from the beginning then let’s do that." Such a meeting took place and I guess we both figured that we’d like to work with each other and several years later here we are.

Robert Frobisher and Vyvyan Ayrs from Cloud Atlas are highly believable figures (pictured left, Jim Broadbent and Ben Whishaw in the film of Cloud Atlas), begging the question of whether you did indeed know your musicological stuff. And do you have a sense of what their music sounds like? Ayrs writes a late piece called Der Todtenvogel, while Frobisher's Cloud Atlas Sextet impresses your young protagonist Jason Taylor in Black Swan Green.

Robert Frobisher and Vyvyan Ayrs from Cloud Atlas are highly believable figures (pictured left, Jim Broadbent and Ben Whishaw in the film of Cloud Atlas), begging the question of whether you did indeed know your musicological stuff. And do you have a sense of what their music sounds like? Ayrs writes a late piece called Der Todtenvogel, while Frobisher's Cloud Atlas Sextet impresses your young protagonist Jason Taylor in Black Swan Green.

It was a conjuring trick. I cribbed most of the musicology from CD sleeve booklets and have no musical training at all. Links between Vyvyan Ayrs and Delius are quite apparent for anyone who knows a bit about Delius’s life. I was putting him in the late romantic Delius/more experimental Vaughan Williams and of course some flashes of Elgar tradition. Delius and Vaughan Williams impressionism melts into something rather more modern on occasion. And I would have put Robert Frobisher as messier. Debussy is a good crossover guy. He has one foot firmly in the 19th century - there are moments when it’s Chopin and Saint-Saëns - but there are other moments in the orchestral work or the preludes where it really sounds decidedly mid-20th century. So Messiaen and the more modernist Debussy. But he has a soft spot for Scarlatti as well. There seems to be this odd bridge between the mid-20th century and the mid-18th that vaults over everything in between.

How does this knowledge of music, described but not heard in your fiction, coupled with your regular job of writing unaccompanied words, go through some sort of funnel at the other end of which you have to write words to go with someone else's music?

A sentence is a kind of musical phrase anyway even when it isn’t being sung

My knowledge and appreciation is there but while it’s there, or what I do have is there, I kind of ignored it when I was working on the librettos. First I started with the story in much the same way as I would write a novella. I get frustrated sometimes with the way 19th century opera gives you so little to bond with in the characters. I feel that often when I watch a 19th century opera there’s little in the characters that allows me to form a real bond. It’s stylised. I feel that the audience has to perform the bond but it’s not actually there. When I write fiction, high up on the totem pole of priorities is the principle that unless you give a damn about the character then why should you spend time reading about what he or she is doing and worrying about it? The answer is you don't and that's when the pages drag by slowly. So when I approached the libretto I did approach it with the same principles in mind. It’s my responsibility to help, if I can, to make the audience care about the characters on stage in the same way that it's my responsibility, if I can, to make readers care about what happens to people on the page. So I approached the libretto from writerly principles first. And what I know and feel and respond to in music wasn’t nowhere but it was at the edge of my vision rather than at the centre of my eye.

That’s how I tried to build the stories and the characters that stories are made of. However, then of course you have to write the lines and dialogue or the arias and what the characters say. There is rhythm and a sentence is a kind of musical phrase anyway even when it isn’t being sung. I feel every sentence has its own musicality and it may be a mellifluous phrase and it may be much more staccato but it’s there. The eyeball can hear it when you read and I believe this is why when you’re making those thousand and one decisions about what this sentence will be, your own inner ear is informing these decisions. I always think "maybe" or "perhaps" mean exactly the same thing but you somehow know when to use one and not the other. How could you know that? The meaning is identical, the register is identical. They are both exactly the same, but you still know. I believe it’s your eyeballs are telling you the right one. So when I wrote the lines for the libretto of Sunken Garden I tried to use what I know about alliteration and rhythm and half-rhyme and the way we pitch and use intonation and stress and make sentences.

When you and Michel van der Aa sat down for your meeting, how did the narrative come about? (Pictured above, the vertical pond in the set design for Sunken Garden. Photograph © Joost Rietdijk)

When you and Michel van der Aa sat down for your meeting, how did the narrative come about? (Pictured above, the vertical pond in the set design for Sunken Garden. Photograph © Joost Rietdijk)

At the very first meeting we started talking about what we were working on at the time. Michel was working on a cello concerto and I was working on a cycle of five stories about a soul snatcher who can perform an alchemy that allows her to convert souls of the lost and the lonely into her own immortality. If her victims are not quite lost and lonely enough then she will give them a push in the right direction. This was a cycle of five stories set in different decades between the Thirties and the present day, all with the same unchanging protagonist. Michel saw the operatic potential in it and said, "How about it?" I said, “OK, let’s give it a go and see what happens." These five stories would need an HBO-type box set so we just chose one of the five and that was the story where the soul snatcher meets her match.

Lyricists in musical theatre don’t usually care to be asked the boilerplate question, “Which comes first – the words or the music?” But it seems appropriate to ask whether you were presented with music or whether you presented the composer with words.

Michel did me a great favour of making my life much easier. I presented the composer with the words. A handful of times he came back to me and said, "I’ve got a great piece of music but I can’t make this fit. Can you do something about it please?" I love that kind of Sudoku-type challenge so I was very happy to oblige but in 99 percent of the libretto the words were the first. It was particularly appropriate because Toby, one of the three main characters, is a wannabe filmmaker, he’s shot footage of interviews of the nearest and dearest of the missing persons, so chunks of the libretto aren’t actually sung, they are screen monologues spoken to an interviewer behind the camera, who is Toby singing onstage in the opera.

Part of me was thinking, I know this line, that’s mad! I wrote it 10 years ago in a back bedroom in Ledbury

Have the other four stories bitten the dust?

At the moment they’re in limbo but they’re fairly strong so at some point I’d like to bring them out of limbo. I start a new book with a chronically over-ambitious idea and part of the writing of the book is to scale it down to something I can actually do, that is physically possible within four years. Cloud Atlas was nine sections instead of six, three in the past, three in the present and three in the future. It would have been about a thousand-pager. It’s still not a very economically viable way to earn a living, but these five stories were embedded in something even larger. When I realised that with this even larger thing I simply couldn’t do it – I’d be writing in 20 years – a lot of those fell away but these five remained. There was a chance they might have morphed into the novel I’m trying to finish now but they didn’t. The novel I’m doing now is sort of set in the same world but it’s a different zone. So they are related but different entities, a bit like the Madame Crommelynck hyperlink between Black Swan Green and Cloud Atlas.

Did you think twice about lifting a character out of Cloud Atlas, advancing her for the best part of 50 years and parking her in the Worcestershire of your childhood?

No. When I can and when it doesn’t seem contrived I do. I like to think of everything I do as chapters in one bigger über-novel and the libretti are also chapters in the über-novel.

As Jason says in Black Swan Green, “Once a poem’s left home it doesn’t care about you.” Did you have qualms about allowing Cloud Atlas (pictured right) to be turned into a film, and letting the Belgian sections, for example, be moved to Scotland?

As Jason says in Black Swan Green, “Once a poem’s left home it doesn’t care about you.” Did you have qualms about allowing Cloud Atlas (pictured right) to be turned into a film, and letting the Belgian sections, for example, be moved to Scotland?

I just had faith in the directors [Tom Tykwer, Andy Wachowski and Lana Wachowski]. Perhaps even when their own faith wavered. And maybe it was an informed faith but isn’t faith always uninformed? Isn’t that the point of faith? You don’t have proof so you have faith. And I wasn’t sure how they could do it but that didn’t mean that I wasn’t going to believe that they could. If you’re going to be precious then don’t sell the rights to your books. No one makes you do it at gunpoint. It’s your choice. I wanted Cloud Atlas to be reinterpreted through the directors’ own creative prisms and I was more curious and sometimes tickled by the changes they did make to the book than I was feeling that my nose was put out of joint. Part of me was thinking, I know this line, I wrote that, that’s mad! I wrote it 10 years ago in a back bedroom in Ledbury. Another part of me was just swept along by the narrative and the relentless eyeball-grabbing scene after eyeball-grabbing scene, and this roller-coaster ride that I couldn’t get off until two hours and 40 minutes later and it only felt I’d been there for an hour.

Jason compares handing over new work to lying in a coffin and awaiting a stake through the heart. Is it like that too when presenting a new libretto to a live audience?

What is somewhat contradictory but still nonetheless true is that you have to develop a thicker skin than you start off with because you’d otherwise stop producing work. I try and take refuge in the truism that whatever you do is going to be Marmite. Some people will love it and some will hate it. What matters is that they hate it because of their own taste and not because there is something inherently wrong in what you’ve done. You make your hide thicker by trying to develop your craftsmanship to the point where you can have an imaginary conversation with a hostile critic and say, ”OK you hate it but I know this is a well-rounded character and a well-plotted story arc. Or at least it's the best I can do.” And that at least gives you some comfort when people are so acid in the face of your beautiful creation.

Does it give rise to confusion that there is another David Mitchell?

I think this is the same for the other David as well but I do occasionally get an invitation via my agent which is comically inappropriate and I think, OK, this one’s for the other guy and so I send it back to my agent and a slightly red-faced email comes back saying, “Oh yes it was.” But that’s about it. It’s hard to quantify how many people going to the opera will think it’s going to be like Peep Show or The Unbelievable Truth. In which case I can only apologise. I guess the internet is there to help people work it out in advance. If we both stick around then eventually more and more people will know there are two and they need to check who we are before they hand over their credit card details. But at least he’s good at what he does.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment