Q&A Special: Memories of Lutosławski | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Memories of Lutosławski

Q&A Special: Memories of Lutosławski

In his centenary year Poland's greatest 20th-century composer is remembered by colleagues and family

While the history of 20th-century music is undoubtedly the history of the 20th century – from the decadent expressionism of fin-de-siècle Berlin to the imagined surrealist worlds of 1920s Paris – few composers lived or wrote the century quite as vividly as Witold Lutosławski. He is celebrating his centenary this year.

Fleeing Warsaw as Prussian forces approached in 1915 for the false haven of Moscow, the young Lutosławski would see his father and uncle arrested and executed by the Bolsheviks. Returning to Warsaw in time for the German invasion, the composer himself was captured, eventually escaping and walking the 250 miles home to Warsaw. Unable to make a living writing his own music, Lutosławski instead performed cabaret music in cafés with fellow compser Andrzej Panufnik. Although the two created hundreds of arrangements and compositions for these performances, only one now survives; the rest were all destroyed in the bloody massacre of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, just days after Lutosławski was forced to flee the city.

He was remarkable. I wanted to be like him, I wanted everyone to be like him

The years of Soviet rule saw Lutosławski’s First Symphony banned and the composer forced to bow to aesthetic pressure from the government. But refusing to defect like Panufnik and others, the composer held out in Poland, continuing to compose against all odds, carving out a role as the country’s most eminent musician and a staunch supporter of individual freedoms and self-expression. He died in 1994 – surviving long enough to see Poland freed from Communist rule, but not quite long enough to complete the violin concerto he had so tantalisingly begun to work on.

His legacy, both musical and personal, was immense, as any conversation with the musicians he worked with, the family he lived with, and the many young musicians who benefitted from his discrete philanthropy, attest. They tell the story best of all, so here, in the words of conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen, cellist Andrzej Bauer and Lutosławski’s stepson Marcin Bogusławski, is the story of Witold Lutosławski.

Page 2: Esa-Pekka Salonen. Page 3: Lutosławski’s stepson Marcin Bogusławski. Page 4: cellist Andrzej Bauer.

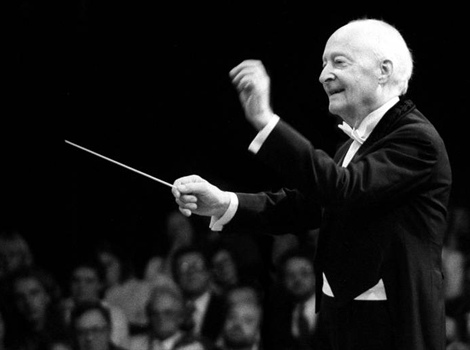

Esa-Pekka Salonen (pictured right) is the principal conductor of the Philharmonia Orchestra, who this month launch a season of concerts devoted to Lutosławski’s music – Woven Words.

Esa-Pekka Salonen (pictured right) is the principal conductor of the Philharmonia Orchestra, who this month launch a season of concerts devoted to Lutosławski’s music – Woven Words.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: I believe you had quite a close relationship with Lutosławski?

ESA-PEKKA SALONEN: I miss him. I think of him often and there are moments when I find it very hard to accept that he is no longer with us. He was remarkable. Sometimes as a young musician you admire someone tremendously and then you get to know them and get disappointed because you realise that either ethically or personally this artist isn’t what you were expecting him to be, or you see weaknesses, or worse. But in this case I only admired him. I wanted to be like him, wanted everyone to be like him.

What was your first encounter with Lutoslawski’s music?

I was a student at the Sibelius Academy and he came on an official visit. I went to his lecture and heard the concert he conducted – I think it was his Livre pour orchestra and the Second Symphony – and was very taken by his music. I felt that it was very powerful and well crafted but yet very direct and immediate – something I could understand, which was not always the case with new music of the 1970s.I was too shy to go and talk to him afterwards; I was dying to, but was sweating too much, so I think I just said “hello”, Finnish-style, and that was it.

It was a few years later that I finally met him. That was in the mid-1980s, and I was asked to share conducting duties with him for the Lutoslawski festival at the Southbank with the Philharmonia, so I went to see him in Bern in Switzerland to discuss the programmes. He was terribly nice to me and I think he was quite touched to see my enthusiasm and admiration for his work. Of course I had millions of questions and was trying to blurt them out all at once. If I had to identify one two-hour period in my life where I learned the most it would be that lunch I think, at least in musical terms. It was a very concentrated learning experience. From that moment on we stayed in touch until the very end. Of course I was very eager to impress, so I was stupid enough to run my analysis of his Second Symphony by him. I’ll never forget the reaction. He told me an anecdote about Hindemith and Hermann Sherchen, when Sherchen was assisting Hindemith at the premiere of Mathis der Maler and had found similar “mistakes” – the composer deviating from his own harmonic system. So he pointed this out to Hindemith who, according to Lutoslawski, said: “My dear Hermann, if you don’t make it as a conductor you will make a fantastic proof-reader.” I felt like a puppy that had peed on the carpet – gently but firmly moved outside. But even that was a learning experience of value.

In subsequent conversations did he offer any further thoughts on his music, or correct any misconceptions?

What he was always keen to emphasise was not the aleatoric element of his music, which on the surface was the most striking and the most easily identifiable aspect of his music. He never thought that this was a particular important part of his music. For him it was just a practical solution to creating complex textures without having to resort to the hopeless maze of septuplets and crazy timesignatures which were quite frequently used by composers at the time. He was proud of his formal inventions though, and the control over form that he exercised in almost everything he wrote since the First Symphony. The way he built his structures was trying to draw the listener into the psychological process of form – creating some expectations then leading the listener astray or teasing them, then finally showing the right way.

Lutosławski always rejected any kind of programmatic interpretation or attempt to give "meaning" to his works. Do you think this really the case – is it pure abstraction?

I can only speak from my intuition because he never would have acknowledged a programme to me or to anyone else, but there certainly is a very powerful narrative quality to his music. And I think that the most easily identifiable emotional narrative is the post-catastrophe moment of reflection. The image I always have is of an old couple walking hand-in-hand through ruins which are still smoking, and not even trying to find their possessions or their family members. They are just silently walking through the devastating landscape. There are several pieces where this narrative is very powerful, but in many cases it gets too personal, and he decides that he doesn’t want to lead his listeners to this place so he writes a jolly, optimistic coda with bells and whistles, quite literally: short, powerful endings that sometimes really doesn’t sound true. I think it’s almost like a sense of musical duty, of the responsibility. You can’t leave your audience in a desperate place, you have to give them a tool to dig themselves out of the grave. He was that kind of a guy. It’s all about responsibility.

I can only speak from my intuition because he never would have acknowledged a programme to me or to anyone else, but there certainly is a very powerful narrative quality to his music. And I think that the most easily identifiable emotional narrative is the post-catastrophe moment of reflection. The image I always have is of an old couple walking hand-in-hand through ruins which are still smoking, and not even trying to find their possessions or their family members. They are just silently walking through the devastating landscape. There are several pieces where this narrative is very powerful, but in many cases it gets too personal, and he decides that he doesn’t want to lead his listeners to this place so he writes a jolly, optimistic coda with bells and whistles, quite literally: short, powerful endings that sometimes really doesn’t sound true. I think it’s almost like a sense of musical duty, of the responsibility. You can’t leave your audience in a desperate place, you have to give them a tool to dig themselves out of the grave. He was that kind of a guy. It’s all about responsibility.

Why do you think Lutosławski has been comparatively so neglected in the UK?

I was at a dinner with him a few years before he died. He had this habit of cracking unexpected jokes and he said, “You know, Esa-Pekka, dying is a very bad career move”. I will never forget that. And of course the pattern is quite often exactly that – once a major composer dies then they slump in exposure and performances. Often the curve does start to tilt up again, and I think Lutosławski is coming to that point. Now I think the true value of his music is being rediscovered and reassessed.

Do we get things from his music that we don’t get elsewhere in 20th-century repertoire?

Yes. I absolutely think so. I would say it’s the experience of form, the experience of a narrative which is very unique. I cannot think of any other composer since Beethoven with this dynamic approach to form.

Page 1: Introduction. Page 3: Lutosławski's stepson Marcin Bogusławski. Page 4: cellist Andrzej Bauer.

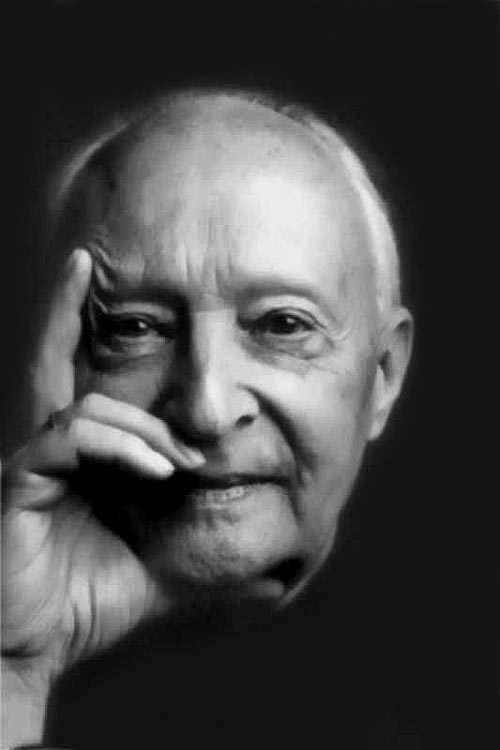

Marcin Bogusławski is Lutosławski’s stepson, and lived with the composer since his early childhood. Today he still lives in the modest Warsaw house that was formerly shared by the composer and Bogusławski’s mother.

Marcin Bogusławski is Lutosławski’s stepson, and lived with the composer since his early childhood. Today he still lives in the modest Warsaw house that was formerly shared by the composer and Bogusławski’s mother.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: Do you have memories of Lutosławski composing at home?

MARCIN BOGUSLAWSKI: He spent the whole day in his study, which still has two doors to this day. He was a perfectionist –every day he was here behind the two doors from 9am-12 pm, at which point he and my mother would drink coffee on the terrace. And then again, after the coffee, he would continue to work, and even my mother was not allowed to disturb him. He was a very private man, so even she didn’t know at the end of a day if he spent it writing letters, polishing his nails or having the most creative day of his life. He very seldom spoke about his work; it had to be something extra-special for him to mention it.

What was Lutosławski like socially?

What was special about my stepfather is that he was a listener not a talker. Everyone likes to talk and likes to present their own knowledge, but he very seldom spoke. He wanted to listen and learn more from those around him. His friends were those with an advanced level of knowledge – philosophers, writers – so that he himself could gain new knowledge about new ideas. It is seldom that someone would rather listen than talk himself.

I read that he often became quite emotional when listening to his music performed. Did you ever see that?

Yes, he had very deep feelings about music and art. I remember when we went on holidays his relaxation was only ever half-relaxed. I remember that it was very difficult on summer holidays to explain to people that we needed a big table for him to lay out all his scores and materials. He would be studying his own music and putting on all his own markings which would change from one concert to another. He never tried to compete with anybody; he had his own way which he followed all his life, and it was no problem for him if other composers in Poland or abroad achieved great things. Artists are often very competitive but he never had this problem. He also believed that talent was no excuse for bad humour, for being explosive or behaving badly. He saw it as his duty to take care of his talent.

Page 1: Introduction. Page 2: Esa-Pekka Salonen. Page 4: cellist Andrzej Bauer.

Andrzej Bauer is a professional Polish cellist, whose early encounter with Lutosławski had a profound impact on his career.

Andrzej Bauer is a professional Polish cellist, whose early encounter with Lutosławski had a profound impact on his career.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: How did you first meet Lutosławski?

ANDRZEJ BAUER: At the beginning of the 1980s I played a recital that was broadcast simultaneously on television and radio, and Lutosławski happened to watch it. My father is a composer and they met in Warsaw; Lutosławski asked about me, saying that it was his wish to help me with the start of my career and to meet me. And so I was sent to study in London for two wonderful years. The fact that he gave me that scholarship was like a fairytale. In gloomy, 1980s Poland it was a miracle. I wouldn’t have been able to afford that kind of study of experience without his help and generosity. He helped a lot of young musicians, and he also financed surgical operations for children. He did all this unofficially; he never wanted to speak about it. Even today we don’t know exactly who he helped.

Why do you think he did this?

He was a person with very high moral values and he did it probably because he felt responsible for the younger generation. He always said that he had too much, that he couldn’t spend all the money he earned, so he just wanted to help people.

What was he like in person – did this same kindness also extend to his professional interactions?

The most important thing about him apart from the music was that he was very good listener – that’s quite unique. He was truly polite and controlled, even to people asking him stupid questions or asking him for a favour. He was a wonderful person to talk with because he listened and was a creative listener – it was always a joy to converse with him and to be with him.

Did you discuss his own music with him?

He mentioned many times in relation to his Cello Concerto and also his Third Symphony that there were tendencies to put some political meaning to the piece, but he rejected that completely. That was Rostropovich’s idea – he created an awful lot of myths.

Page 1: Introduction. Page 2: Esa-Pekka Salonen. Page 3: Lutosławski’s stepson Marcin Bogusławski.

- The Philharmonia Orchestra begin their Woven Words season dedicated to the music of Witold Lutosławski on 30 January

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

Add comment