Interview: Martin Crimp in the Republic of Satire | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Martin Crimp in the Republic of Satire

Interview: Martin Crimp in the Republic of Satire

The innovative playwright discusses his unseasonal new play for the Royal Court Theatre

Playwright Martin Crimp defies labels. He has been called obscure and oblique, too difficult and, worst of all, too Continental. But although he is feted on the European mainland — George Benjamin’s opera Written on Skin, with text by Crimp, comes to the Royal Opera House next spring but it began its much-lauded European tour in Aix-en-Provence — he is also a quintessentially British playwright: his style is colloquial, socially aware and politically acute.

When I meet him at the Royal Court, where his latest play opens this week, he seems almost part of the furniture. His work is the great tradition of experimental modernists such as Samuel Beckett, Caryl Churchilll and Sarah Kane. But, alas, that too is a label. And perhaps misleading — at first, his new play is mysterious. It is intriguingly titled In the Republic of Happiness and it’s running during the Royal Court’s Christmas slot, which typically features more light-hearted fare such as Get Santa!. Has the austere playwright become a writer of festive jollities?

The tall, grey-haired, bony-faced, 56-year-old Crimp (pictured below, © Grégoire Bernardi) chooses his words with great care, yet maintains a friendly air. He despises lazy journalism, but I have done my homework. In the Republic of Happiness is his first full-length play since The City, which was staged here in 2008. It reads like it’s his most experimental work since his 1997 masterpiece, Attempts on Her Life. But surely, isn’t it much too abrasive to be a Christmas show?

“The fact that the play is being staged at Christmas is a coincidence,” says Crimp. “Of course, in my mind it follows on from my play The City, of which the last scene is a Christmas scene. So in a way I am revisiting that, and carrying on from where I left off at the Christmas moment. And I suppose for years and years I’ve had this plan of somebody interrupting a meal with very long speeches. So now I finally did it.” So although the publicity says that “a family Christmas is interrupted by the arrival of Uncle Bob”, this, he reiterates, is not a Christmas play. It is not a festive play - although it is an entertainment, and naturally he hopes it will be entertaining.

“The fact that the play is being staged at Christmas is a coincidence,” says Crimp. “Of course, in my mind it follows on from my play The City, of which the last scene is a Christmas scene. So in a way I am revisiting that, and carrying on from where I left off at the Christmas moment. And I suppose for years and years I’ve had this plan of somebody interrupting a meal with very long speeches. So now I finally did it.” So although the publicity says that “a family Christmas is interrupted by the arrival of Uncle Bob”, this, he reiterates, is not a Christmas play. It is not a festive play - although it is an entertainment, and naturally he hopes it will be entertaining.

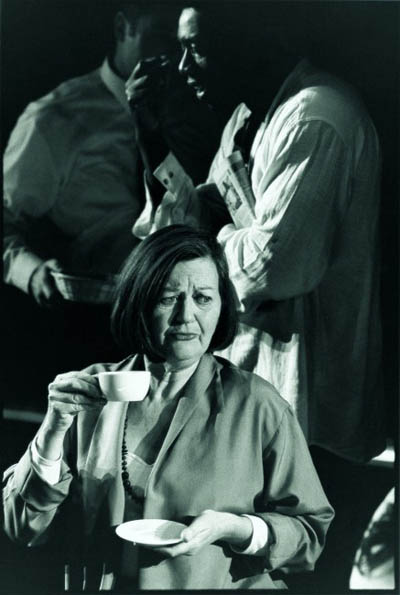

When I ask Crimp where it comes from, he casts an over-the-shoulder glance at his recent work. “As you know, I wrote The City in response to my The Country, which started me thinking of plays as pairs. So they were two psychological plays that formed a pair. And for years I have been trying to write a play that would go alongside Attempts on Her Life, which is the kind of play that sets out to create a sieve in which you could collect all the residue, all the psychic shit that flows through us all.” So Attempts on Her Life (pictured below, © Ivan Kyncl) is “one collection of psychic debris” and the central section of this new three-part play is another collection of psychic debris: it’s more about a contemporary mentality than about character and plot.

Looking at the opening scene, which is imbued with a feeling of dark hilarity, I ask the playwright to tell me something about this unfestive family. “I do have some clear ideas about them,” he says, “and they are present within the text, and when you analyse it — as we have to do in the rehearsal room — we can see there’s something quite specific there. We know that the father in the family processes planning applications so he has a reasonably middle-class profession. We know that his mother, the grandmother on stage, talks about her time as a GP. And grandad talks about the fact that he’s run a number of businesses, or enterprises, which have failed.”

Looking at the opening scene, which is imbued with a feeling of dark hilarity, I ask the playwright to tell me something about this unfestive family. “I do have some clear ideas about them,” he says, “and they are present within the text, and when you analyse it — as we have to do in the rehearsal room — we can see there’s something quite specific there. We know that the father in the family processes planning applications so he has a reasonably middle-class profession. We know that his mother, the grandmother on stage, talks about her time as a GP. And grandad talks about the fact that he’s run a number of businesses, or enterprises, which have failed.”

That’s a good thumbnail sketch, but what is the message? Crimp isn’t keen on explicating meaning, but he has a clear idea of this family. “I suppose that in my mind they are suffering from generational entropy, if you like. So the grandparents are the wealthy middle class, who both had good professional standing and a steady income, but their children have moved down the social scale, either because they have chosen to rebel against their parents, or simply because that’s how life has turned out. And we don’t really know how their children, the newest generation, will turn out. But the signs are not particularly good. One of the girls is already pregnant at a young age.”

Instinctively he’s tapping into a phenomenon that even sociologists haven’t quite grasped: reverse social mobility – that future generations will be poorer than we are. “Social entropy is a downward social mobility, and the opposite of the idea of upward social mobility, and the opposite of my own trajectory,” he says. “But I don’t want the audience to condescend towards my family so I think that the mother and father should be normal people, which the audience might recognise as themselves.” Crimp is in the middle of rehearsals and the production is being directed by Dominic Cooke, the outgoing artistic director of the Royal Court (pictured with cast above). During our talk, Crimp’s favourite phrase — as he himself points out — is “As I’ve got older”. He says that he has been thinking about the changes in society after the Second World War, and that his play, and in particular its savagely satirical central section, is partly a criticism of the myths of upward social mobility in postwar Britain, and in particular the myth of individualism which, in our culture, so quickly becomes narcissism.

Crimp is in the middle of rehearsals and the production is being directed by Dominic Cooke, the outgoing artistic director of the Royal Court (pictured with cast above). During our talk, Crimp’s favourite phrase — as he himself points out — is “As I’ve got older”. He says that he has been thinking about the changes in society after the Second World War, and that his play, and in particular its savagely satirical central section, is partly a criticism of the myths of upward social mobility in postwar Britain, and in particular the myth of individualism which, in our culture, so quickly becomes narcissism.

Typically, Crimp refers to other cultural forms: “Andy Warhol, who was so prescient, said that ‘In the future everybody will be free to think exactly what they like — and they will all think the same.’ This is exactly what the central part of the play is attempting to dramatise.” And then the playwright goes on to make a political point: “And of course individualism suits the world we are living in very well because we are constantly told that we are free to make choices and somehow the politicians and the leaders of large corporations — who make all the important choices — are allowed to step back and say, ‘Actually it’s nothing to do with us. It’s all choices by our customers.’ And it’s all a lie.” But at the same time, he emphasises that this is not purely a satire — the fact is that people do experience real psychological distress, eating disorders and obsession with their own personal traumas.

Crimp also mentions the coincidence of the Jimmy Savile scandal happening just as one of the things he is talking about in the play is how people’s most life-affirming events are their most private traumas. “Disadvantaged or vulnerable people are thrust into the limelight and their experiences of abuse are exploited in order to sell newspapers or boost television programmes. They have experienced things that should not be in the public domain.” It’s hard to disagree with that.

But what about the title of the play? This — along with the headings of each of its three sections — seem to refer to mighty moments in political history from the late 1960s: “The Destruction of the Family”, “The Five Essential Freedoms of the Individual” and “In the Republic of Happiness” seem all very Generation 68ish. He nods: “They did come from a thought that I wanted to write a political play that was very far removed from ‘a political play’ and so that means writing a political play which is about disengagement from politics.” He argues that today power lies not with politicians but with the vast amounts of money made by enormous corporations, which governments have become increasingly frightened of meddling with. “So I suppose the titles of my play are a reference to this fact. It’s an attempt, if you like, at writing a political play. So ‘The Destruction of the Family’ sounds like a piece of radical psychology or echoes the title of a piece by Louise Bourgeois entitled The Destruction of the Father.”

Maybe this is just about getting older, but I feel that the past is being undervalued

Nowadays, whenever you think up a title you have the whole internet as a library to make sure that no one has used it already. When Crimp googled “The Republic of Happiness” he found that the “only reference to this idea is a pop festival in Uzbekistan”. A good omen, surely. And there’s more. “My titles are a slightly tongue-in-cheek reference to the discourse of the late 1960s and 1970s, but equally when you look at some of the theatrical and artistic artefacts of that time, there’s a certain countercultural impulse there, a questioning and destructive impulse which has largely vanished from the arts. The second part of the play is very much influenced by a piece by [German playwright] Peter Handke called Offending the Audience.”

When I mention the anti-naturalism of the language of the play, he smiles with recognition. “I always struggle with the genre of naturalistic drama. And as soon as I start writing one I want it to fall apart. I want someone to come in and hit it with a sledge-hammer. In this play, I wanted the naturalistic world to fall apart as we watch it. Clearly, without giving too much away, when Uncle Bob arrives, he is signalling both the end of this family and the end of this play being a conventional naturalistic play...”

Another obvious theme is dementia, which is mentioned more than once. “Clearly,” Crimps says, “that did come from personal experience seeing one of my parents suffering from dementia. It’s a very present part of the world now as people are living longer. Of course, it’s also in the culture – have you seen that beautiful film by Michael Haneke [Amour]? But also there’s something going on in the play about a lack of memory: the past is retreating at speed and people wanting to live in a perpetual present. And, maybe this is just about getting older, but I feel that the past is being undervalued. I realise how close my date of birth [1956] is to the end of the war. And I know that there is a generation of people who have no idea about that history.”

In the Republic of Happiness (pictured left) is a surprisingly angry play: it pulses with hot emotions. “You are,” I venture, “more angry now than when you started out.” Another half-smile: “I think there’s a reason for that,” he says. Because of his wife, who worked as a senior figure in the NHS, he has been close to what has happened to the Health Service. “A huge public institution is being dismantled in the name of individualism, choice and the market, and I have seen the corrosive effects of that at first hand. So I do feel an intense anger about that, and I’ve tried to encapsulate this feeling in the play. That’s one of the angry seeds within the play.”

In the Republic of Happiness (pictured left) is a surprisingly angry play: it pulses with hot emotions. “You are,” I venture, “more angry now than when you started out.” Another half-smile: “I think there’s a reason for that,” he says. Because of his wife, who worked as a senior figure in the NHS, he has been close to what has happened to the Health Service. “A huge public institution is being dismantled in the name of individualism, choice and the market, and I have seen the corrosive effects of that at first hand. So I do feel an intense anger about that, and I’ve tried to encapsulate this feeling in the play. That’s one of the angry seeds within the play.”

The domination of our lives by capitalism also makes Crimp angry, but he is typically self-reflexive about the emotion. “I know it makes me sound like an adolescent or a teenager,” he says, “but I am very angry about consumer goods – each new generation of gadgets comes out and people have to spend more money to buy them. But why? Are they so much better than the previous ones? Does it make people feel better? No, no, no. Self-reported happiness in ‘advanced western democracies’ is less as your income goes up.”

As ever, there’s a wider point to be made. “Everybody once believed that we would advance so much technologically that we’d have limitless free time, but the opposite has happened. People take their work home. Nowadays, in any high-powered firm you are given a Blackberry, which you’re expected to keep on all the time.” As we drain our austere glasses of mineral water, we decide to call it a day, and go for a drink in the Royal Court bar. But we leave our mobile phones turned off. Work can wait.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Add comment