theartsdesk Q&A: Director Emma Rice | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Emma Rice

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Emma Rice

Why Kneehigh may roam far and wide, it will always return to its Cornish roots

Based in a collection of barns on a cliff top near Mevagissey on the south Cornish coast, Kneehigh theatre company has always looked defiantly away from London and out towards the sea and the wider world. This streak of independence runs right through the heart of the company, which produces extraordinarily inventive, highly visual and sometimes surreal work that has been seen all over the world, from Australia to Colombia to Broadway and, yes, the West End.

Rice joined the company in 1994 as a performer and directed her first show, The Itch, for Kneehigh in 1999, although it wasn’t until The Red Shoes for which she won a Theatrical Management Association Award for Best Director that she became known as a director rather than an actor. Since then she hasn’t looked back and her shows, which in true Kneehigh tradition involve collaborations with musicians, poets and puppeteers, include The Wooden Frock (2004), The Bacchae (2005), Tristan and Yseult (2006), Rapunzel (2007) and Don John (2008). Her production of Brief Encounter, which cleverly switched between Noël Coward’s original stage play, Still Life, and sequences from David Lean’s film Brief Encounter, was a huge success in the West End and transferred to Broadway, and her last show, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, has just finished a run in the West End. She is also currently joint artistic director of Kneehigh, alongside Shepherd. (Pictured above: Patrycja Kujawska in the 2010 revival of The Red Shoes.)

That’s not to say that Rice’s career has been a completely smooth and starry upward trajectory. Some of her finest work, such as The Red Shoes, has been inspired by difficulties in her personal life and A Matter of Life and Death (2007), a co-production with the National Theatre, was given such a roasting by certain critics that Nicholas Hytner, the artistic director of the National, felt obliged to denounce them publicly as “dead white men” – although several of the reviews were, in fact, very favourable.

That’s not to say that Rice’s career has been a completely smooth and starry upward trajectory. Some of her finest work, such as The Red Shoes, has been inspired by difficulties in her personal life and A Matter of Life and Death (2007), a co-production with the National Theatre, was given such a roasting by certain critics that Nicholas Hytner, the artistic director of the National, felt obliged to denounce them publicly as “dead white men” – although several of the reviews were, in fact, very favourable.

She talks to theartsdesk about her career and her two new pieces of work for Kneehigh, Midnight’s Pumpkin and The Wild Bride.

HILARY WHITNEY: When did you first become interested in theatre?

EMMA RICE: I was brought up in Nottingham, although my parents were both from the South West originally, both from very working-class families and the first generation to have gone into higher education, and I think they had a very strong social conscience and cultural aspirations. They were fantastic parents - to some extent they were the first generation in their families to experience the arts and theatre, so they took us everywhere. I remember watching ballet at Nottingham Theatre Royal, literally in the £5 seats right at the top. At that time, which was the Seventies, Nottingham Playhouse was run by Richard Eyre and it was a fantastic place - Jonathan Pryce came through there, Imelda Staunton came through as a young actress and it was actually a place that young people went to. I have great recollections of how exciting going to the theatre was and getting all dressed up because it was such a big event, so I think it was really my parents’ and their friends’ love of it that rubbed off on me, that encouraged me to think that theatre was the most exciting thing, something magical. The Playhouse also did great children’s work with Sylvester McCoy.

And when did you start thinking this was something you might do yourself?

I went to a very ordinary – well, it wasn’t ordinary, it was extraordinary actually – all-girls comprehensive in Nottingham with a very large immigrant contingent - a lot of Eastern European girls, Polish girls, West Indian girls, and a large Asian community, which is why it was single sex. Academically it was appalling – all they really wanted to do was make sure we didn’t go on the streets because there’s a really famous red-light district in Nottingham, so we had more sex education than anything. Actually, I recall very little of it but the main thing was that I think I knew I wanted to be an actress when I was in my mid-teens, but I didn’t do any acting at school because I think I realised, on some very wise level, that it was far too embarrassing to do when I was at school.

Did you think people would take the mickey?

Yes, I just survived school. I just put my head down and waited for it to be over and one day, fantastically, it was. I don’t understand people who say your school days are the best years of your life - I just tried to get through them.

But did you do any drama outside school?

No. I did absolutely nothing. I just waited. But then I went to do A levels at an FE college, which was brilliant. I came out of it with two A levels and life-long friends. There was a little drama studio that’s long since been demolished and we just made theatre. We did this brilliant thing where we made a piece of theatre every week and there was a rota as to whether you did the lighting or you wrote it or you designed it or you acted, and we lived for it, all of us. And it’s funny, because I think after about 20, 25 years, I’ve recreated that – it was very much like being at Kneehigh.

So you were studying drama there?

I was studying English and stage décor and design and because it was a vocational course there was lots of drama training going on – which wouldn’t be possible now. But just out of interest, that year was a stellar year – Jonathan Church, who runs Chichester Festival Theatre, was there, as was Sam Beckinsale, who had a very successful acting career, and Samantha Starbuck, who’s a television producer, and quite a few others and we all still know each other, it’s really phenomenal. It was a much more successful group than at my drama school – something magical happened in the old shack in Nottingham.

I was studying English and stage décor and design and because it was a vocational course there was lots of drama training going on – which wouldn’t be possible now. But just out of interest, that year was a stellar year – Jonathan Church, who runs Chichester Festival Theatre, was there, as was Sam Beckinsale, who had a very successful acting career, and Samantha Starbuck, who’s a television producer, and quite a few others and we all still know each other, it’s really phenomenal. It was a much more successful group than at my drama school – something magical happened in the old shack in Nottingham.

Then I got a place at Guildhall [drama school] and did the professional acting course. I had a great time but then I was 18 and I’d just left home, so that’s not surprising. With hindsight I don’t have a great approval of the training I had because it was really to make people become the best performers they could possibly be in order for them to become as successful as they could possibly be. The one conversation that never, ever happened at Guildhall was, “What work would you like to do? Why would you like to do it? What can you bring to it?” There was not even a whisper of ownership of the work. But, having said that, it armed me with a great tool bag of voice and movement and gave me three years to grow up a little bit.

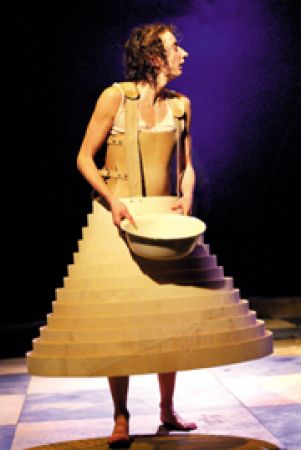

After Guildhall I had a fairly – well, it wasn’t terrible, I was just a struggling not-that-special actress. I got a rehearsed reading at Leicester, I did a funny little show about lanterns, that sort of thing. (Pictured above: Amanda Lawrence in The Wooden Frock.)

Lanterns?

Magic lanterns. In Warminster or somewhere. I was pretty much unemployed and I was never going to make it as an actress really, but there was a period where I had three auditions at once and things started to look up. One was with the RSC to be part of the ensemble and I had three recalls for that. I also auditioned to be Michael Elphick’s sidekick, his sort of secretary, in the TV series Boon, which meant I would have been in every episode and I had three recalls for that as well, and then there was an open call for a company called Theatre Alibi based in Exeter. Of course, I didn’t get either of the first two jobs, which I really wanted - I got the tin-pot company in Devon. I was rather crestfallen when I got on the train to Exeter to do community work and children’s shows, but it completely changed my life. It was a key moment because Theatre Alibi comprised of people who graduated from Exeter University, which is quite a challenging drama degree course, and they were very much on the performance arts side of things. Suddenly I was in this room of people talking about Grotowski and Robert Wilson, names I’d never heard before. We did warm-ups and we talked very seriously about the work.

Did you enjoy it right away or were you intimidated?

I loved it from the minute I got there – and again, made life-long friends and the reason I say that is because I didn’t really make life-long friends at drama school. I had a fine old time but in many ways it was something of a solo experience, I guess. No, I loved Theatre Alibi immediately. I loved being involved – again, it was like going back to those days at Harrington, my FE college, where everybody did everything. I used to love doing a show and then, because you were touring in a van, you’d discuss it on the way home. As soon as you go higher up the pecking order in theatre, you hardly see anybody. You turn up at the half, you sit in a dressing room and then you go home, but the bits I treasure most about working in theatre are talking about the work and the audience – the shared experience of it. So I loved Theatre Alibi and had no intention of doing anything else as long as there was work there.

What sort of shows were you doing there?

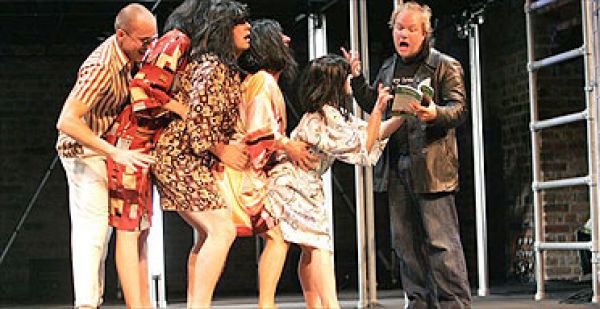

The first show I did was a village hall tour of a Thomas Hardy story and then I did... I’m afraid I can’t remember. I was with them for about eight years so I did many shows, but I also did some children’s work with them which is very storytelling based and I found that very hard to crack as an actor because drama-school training is all about “imagine you’re somebody else, imagine you’re in another room and pretend to be them”, which is all fine but it’s actually quite protected. You can cover up a lot of your own anxieties in that world but in storytelling you have to say, “This is me and I’m in this room with you and I’m going to use my own voice and look you in the eye and start telling you a story.” That story may move or transform or transport but ultimately, you’re never pretending that you’re not yourself and that was a vital discovery for me. Once I’d discovered how to do that, it was very hard to go back because there is a basic truth about that work. So children’s work taught me a lot of skills and beliefs that I’m absolutely bound to even to this day. (Pictured above: The Bacchae)

The first show I did was a village hall tour of a Thomas Hardy story and then I did... I’m afraid I can’t remember. I was with them for about eight years so I did many shows, but I also did some children’s work with them which is very storytelling based and I found that very hard to crack as an actor because drama-school training is all about “imagine you’re somebody else, imagine you’re in another room and pretend to be them”, which is all fine but it’s actually quite protected. You can cover up a lot of your own anxieties in that world but in storytelling you have to say, “This is me and I’m in this room with you and I’m going to use my own voice and look you in the eye and start telling you a story.” That story may move or transform or transport but ultimately, you’re never pretending that you’re not yourself and that was a vital discovery for me. Once I’d discovered how to do that, it was very hard to go back because there is a basic truth about that work. So children’s work taught me a lot of skills and beliefs that I’m absolutely bound to even to this day. (Pictured above: The Bacchae)

I loved touring round Devon schools - getting into a van at 5 o’clock in the morning, performing at 9 o’clock and done by 3 in the afternoon. It was genuinely one of the happiest times because you learn all about audiences, you learn how to keep their interest, and how to make them look in the right direction - because of course you are in school halls with no lighting so you have to be very clear about where people should be looking and I’m still very aware of all of those things, even when I’m working in the West End.

When people are young and they want to be actors, they are often drawn to the glamour – the West End dressing room and your name in lights. Did you ever think when you were driving down some muddy lane in Devon, this isn’t how I thought it would be?

The reality is that I felt at home right away. Now, that doesn’t mean I’m not ambitious because I am incredibly ambitious, but I think from around that time I had ambition for the sort of work I was doing, not just random success for the sake of it. I can’t tell you when those ambitions emerged. I suppose I did like the idea of working with [Theatre de] Complicité, for example, but I also wanted the work I was doing to go to the Edinburgh Festival to get seen and recognised. But did I think, oh, I should be in the West End? No, never.

Did you enjoy living in Devon and being part of a smaller community?

Yeah, but while I was working in Devon I continued living in London for a stupidly long time – because we weren’t working full-time, we were always on contract so I had feet in various parts of the country for ages.

But you also trained with the Gardzienice Theatre Association in Poland.

I’d been with Alibi for about a year when Ali Hodge and Tim Spicer, who ran the company, got a grant for us all to go out as a company to train with Gardzienice, which we did, so I first went out there for about a month and it was tough. Everything about it disarms you. You don’t have enough sleep, you don’t speak the language – although no one talks because it is considered white noise - everything is confusing. Rehearsals start at dusk, which is very funny because the Brit in me just wants to say, “What time is that?” We would always begin with a night run through the forest in the dark and then we’d work by candlelight in this chapel in the middle of what felt like Medieval times. There was one phone we could borrow and the number was three. It was so rural – people were cutting the fields with scythes and old ladies were hand-milking cows. It was like going back to Bruegel. (Pictured above: Tristan Sturrock and Eva Magyar in Tristan and Yseult.)

I’d been with Alibi for about a year when Ali Hodge and Tim Spicer, who ran the company, got a grant for us all to go out as a company to train with Gardzienice, which we did, so I first went out there for about a month and it was tough. Everything about it disarms you. You don’t have enough sleep, you don’t speak the language – although no one talks because it is considered white noise - everything is confusing. Rehearsals start at dusk, which is very funny because the Brit in me just wants to say, “What time is that?” We would always begin with a night run through the forest in the dark and then we’d work by candlelight in this chapel in the middle of what felt like Medieval times. There was one phone we could borrow and the number was three. It was so rural – people were cutting the fields with scythes and old ladies were hand-milking cows. It was like going back to Bruegel. (Pictured above: Tristan Sturrock and Eva Magyar in Tristan and Yseult.)

It’s quite hard to remember it clearly after all these years – I remember the feel of it but I don’t remember the specifics very well. It’s a very physical, European, autocratic system. Włodzimierz Staniewsk, the leader of the troupe, is amazing but he does shout at you and some things you can never get right. This phenomenal art was made but I never truly understood the process and what was happening because I didn’t understand the language and neither did they want me to - it was working on a much more animal level, although that was less so when we trained - because we trained with the company, and then they asked me to go back and join them as a performer.

That must have been very flattering.

[Warily] Yes, well, I went back out with one other girl from Alibi at a later stage for a further couple of months. It was winter and it was really desolate. I literally crossed the days off the calendar. I had no contract and nobody to talk to. I just sort of went out there and I basically ran away at the end. I mean, I went home and never came back.

But were you performed in productions?

Well, I did perform but it wasn’t really as structured as that. You worked through the night until somebody said you could go to bed and you might work 10 days in a row and then they’d say don’t come back for two days, or even longer - 15 days - and then they’d say have a day off, but there was no structure to anything. It was terrifying.

It sounds it. You did get paid, didn’t you?

I think so, but I can’t really remember. I must have done. Anyway, I was with Alibi for about eight years although during that time I was still doing other work. I was working with Katie Mitchell a lot around that time because Katie had been working with Gardzienice as well and at that time, anybody who’d been out there was drawn to each other. We all had an unspoken bond – it wasn’t necessarily even a friendly one, but we’d all had this very extreme experience. It was like a survivors’ group. Katie was very, very influenced by Gardzienice and was looking for people to help her bring that into her work so, whilst working with Alibi, I was also beginning my relationship with Katie. I did many productions with her, first as a performer – A Woman Killed With Kindness, Women of Troy and The House of Bernarda Alba and then I did some choreography for her.

Then you moved to Kneehigh.

Yes, but there was one other key event I must tell you about. It’s funny, because you asked me if I ever wanted to go to the West End and I said no but I was still ambitious, as I say, and I think that there was a bit of me that still wanted to be recognised by the people that my mum and dad rated. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I think I began to get recognised as somebody that was slightly unusual and I got a job at the National in Tony Harrison’s play Square Rounds. I was really thrilled – even though I was doing all this children’s work and had been to Poland - to actually get a job at the National. I don’t know how to tell this story really, whether I tell it from my point of view or their point of view, but from their point of view, I think that having gone to Poland, I was probably pretty much unemployable as an actor because I think I’d learnt a set of rules that didn’t apply to Western work and yet were very ingrained in me because it was such a strong experience. (Pictured above: Rice during rehearsals for The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.)

Yes, but there was one other key event I must tell you about. It’s funny, because you asked me if I ever wanted to go to the West End and I said no but I was still ambitious, as I say, and I think that there was a bit of me that still wanted to be recognised by the people that my mum and dad rated. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I think I began to get recognised as somebody that was slightly unusual and I got a job at the National in Tony Harrison’s play Square Rounds. I was really thrilled – even though I was doing all this children’s work and had been to Poland - to actually get a job at the National. I don’t know how to tell this story really, whether I tell it from my point of view or their point of view, but from their point of view, I think that having gone to Poland, I was probably pretty much unemployable as an actor because I think I’d learnt a set of rules that didn’t apply to Western work and yet were very ingrained in me because it was such a strong experience. (Pictured above: Rice during rehearsals for The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.)

So I think I was probably unemployable but I found myself in a room at the National with the creative team, who were all men, working with a room of all women, just telling us what to do. I didn’t speak for the whole two days I was there - we didn’t even say what our names were, they sort of told us where to move. I couldn’t believe it - they just showed us a model of the set and explained where we were all going to move. I was deeply unhappy and thinking, I don’t know if I can do this, when one of the other actresses left the process. So the creative team called a meeting and I thought, well, this is good – at least we’re all going to get a chance to speak and it will all get sorted out, but we just were told, “If you don’t want to sing and you don’t want to dance, then you shouldn’t be here, you know, get out,” so I did. I left and that was really a key moment for me to walk out because I felt like I’d walked out of the profession and everybody said it would be very hard for me to work again and that it was a really bad career move but at the time I just thought, well, I don’t want this career if this is what it is. It’s not what I’m going to do.

That led to a fairly bleak couple of years, to be honest. I found it very hard to keep working but good did come out of it eventually because that was when I finally moved out of London to Exeter, and made the first piece of work that I felt truly involved with, which was a piece with Dan Jamieson from Alibi called Birthday. Dan wrote it but we created together and it was Time Out Critics’ Choice – it was a beautiful show and that’s when I began to actually start making my own work.

What was it about?

It was a two-hander about Marc and Bella Chagall. It was beautiful and it brought in all the Eastern European influences that I’d been obsessed with and it was also very magical and romantic and lyrical because of all the Chagall images. So leaving the National was a key moment and I never did look back really because that was when I started making my own work. It was also around that time that I met Kneehigh and meeting Kneehigh was really like – I can still be romantic about it because I’m still here – coming home. It was a bit like being in Poland because it was rural and people ate together, but it was happy. Instead of creating pain to make something beautiful there was laughter creating something beautiful. There were people making music, making each other laugh - it’s like a huge family.

So you joined them as a performer, initially?

Yes, I auditioned for them. I was working for Alibi but it wasn’t full-time work and somebody said, “Oh, you should work for Kneehigh,” and I wrote them a letter and got an audition, as simple as that.

I’m very intrigued by Kneehigh because obviously every theatre company is unique but Kneehigh seems to me to be particularly unusual. There is a quote from Mike Shepherd, the founder and co-artistic director of Kneehigh, on Kneehigh's website which says, “The need to cook and keep warm provides a natural focus for our flights of imagination.” I mean, what is that like on a day-to-day basis?

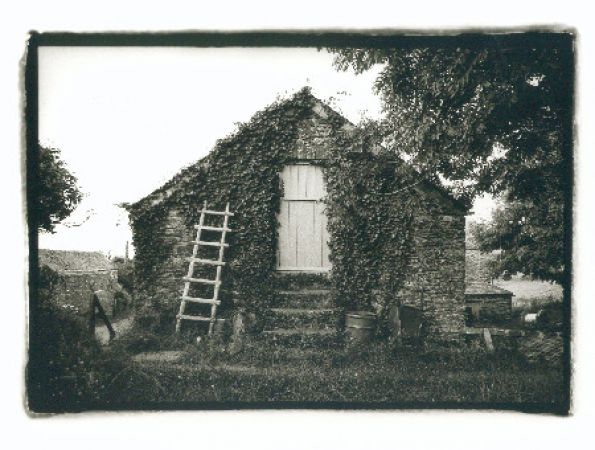

It’s exactly how it sounds. We eat together, we work outside when we can, we light fires. We eat together at every meal because there’s nowhere else to go – you can’t pop out for a cappuccino. It’s like a big camping trip. I often say it’s like a youth club because there are always people playing music, learning dance steps, eating. We only do this for a few months of the year – it’s not a commune, we all have other lives – but when we’re making work, this is where we are and because there’s no rigid sense of where work ends and life begins, what we can do in two weeks, three weeks, five weeks, is extraordinary because we’re working all the time, whether we know it or not. I love it. Sometimes you want to get away from people, sometimes it drives you mad but the truth of the matter is that it’s the best thing in the world and we look at each other sometimes and go, “Look at us! This is fabulous!” (Pictured above: one of Kneehigh's barns.)

It’s exactly how it sounds. We eat together, we work outside when we can, we light fires. We eat together at every meal because there’s nowhere else to go – you can’t pop out for a cappuccino. It’s like a big camping trip. I often say it’s like a youth club because there are always people playing music, learning dance steps, eating. We only do this for a few months of the year – it’s not a commune, we all have other lives – but when we’re making work, this is where we are and because there’s no rigid sense of where work ends and life begins, what we can do in two weeks, three weeks, five weeks, is extraordinary because we’re working all the time, whether we know it or not. I love it. Sometimes you want to get away from people, sometimes it drives you mad but the truth of the matter is that it’s the best thing in the world and we look at each other sometimes and go, “Look at us! This is fabulous!” (Pictured above: one of Kneehigh's barns.)

What’s it like joining a company that is so well established and has such a particular ethos? It sounds extremely welcoming.

Well, that’s probably a whole other article because the interesting thing about any company that chooses to stay together is that you have to regenerate. The only thing that you can’t do is keep things as they are – it simply can’t happen. Most jobs [in performance] are just a collection of freelance people who have come together on that one occasion. Companies are very different because they have to think, what is the next step? And you take some things with you and you change some others but you’re always looking for something new so it’s not welcoming in a sort of hippy, loving way. It’s absolutely welcoming in that if there’s someone new to come in and understand and change the direction of the work, then the arms are open. Certainly, after my own tenure at Kneehigh, I’m always looking at the next catalyst to surprise us and change us and knock us off balance.

When I first joined Kneehigh lunchtimes felt incredibly long because I didn’t know anybody but I can remember thinking, but I will get to know them. It wasn’t uncomfortable, but I can remember being aware that I wasn’t quite one of the gang - but it was OK because I kind of knew I was going to be.

You joined Kneehigh in 1994 but you didn’t direct your first show until The Itch in 1999.

Correct, although I had been devising work. What had happened was that as a deviser, I’d been getting more and more involved in the work and as a performer I was quite dominant in the creation of ideas and, because I’d been choreographing for pretty much everybody, also the staging of ideas. When I was working with Kneehigh I’d run rehearsals while we were on tour – and if anyone did that to me I’d kill them, but I was happily re-rehearsing shows as we went – and in fact it was Bill [Mitchell] and Mike [Shepherd] who were running Kneehigh at the time who said, “Why don’t you just direct Emma?” and I can remember very clearly saying at the time, “Oh, I don’t need to direct! I’m just throwing in my ideas!” So Bill said, “Well, you are a director Emma, so why don’t you give it a go?” so I did and that’s how The Itch happened, although I was very nervous about giving up performing because I felt that that was my passion.

The Red Shoes is considered by the company to be the seminal point when you moved from performer to director.

Yes, that’s true. It was an explosion of all the creative energy that I’d built up over the years. I’d never really considered myself to be an original thinker, I always thought that I was more responsive than anything, so it was really interesting when Bill and Mike asked me what I wanted to do next. I hadn’t thought of anything and then I opened my mouth and I said, “The Red Shoes,” and they said, “Brilliant, let’s do it.” I honestly didn’t know the story, at least I don’t remember being told the story, and I hadn’t seen the film – it literally popped out of my mouth.

Watch a video of The Red Shoes 2010 revival

First of all, because I didn’t realise it was a Hans Christian Andersen story, I went to see the Powell Pressburger film and I thought, this is a disaster! What have I agreed to do? It’s so strange and it’s all about ballet! So I was in a little bit of a flat spin and then I went to the library and found the Hans Christian Andersen story and it was like being hit by a sledgehammer. I just remember sitting in the library in tears because I was at the beginning of my divorce – divorce is the wrong word, it was a separation between the man that I had married and thought I was going to settle down and have children with and live happily ever after - and the story felt as if it was absolutely about what I was wrestling with, which was how could I possibly make somebody else happy and do what I was supposed to do whilst also listening to the demands of my own psyche and my own soul and my own creative needs?

And the metaphor of having one’s feet chopped off is so extraordinary because that’s what it felt like. It felt like a terrible choice – I was chopping something off no matter which way I looked. I was either chopping off this chance of simple happiness or I was casting off the possibility of expression and ambition and being an artist, because the work had become very, very personal at that point. Having said that, I’m making it [the production of The Red Shoes] sound like a soap opera and it was nothing of the sort. It was a very stark, bold, brazen piece.

It was a very, very difficult time personally. I wasn’t in an unhappy relationship. He [Rice's husband] was fantastic, which made it even more difficult, and I remember my mother saying – we didn’t talk much about it, but she did say this – that there’s very little in literature or culture that talks about or explores that situation. Everybody talks about unhappy marriages all the time, we get that, don’t we? But what we don’t get is why somebody would leave a pretty happy marriage. And that’s why something like The Red Shoes is a very profound and complex narrative path to tread because actually it’s about how one functions as an individual. There is no romance or happy ending, it is about one’s own bargains with yourself, which is certainly what it felt like at that time in my life.

So how do you start putting a production together?

I always start with the theme. I don’t know whether I’m lazy or whether I’m inspired – let’s stick with inspired! – but I do very little research. I’m a great believer in circling the idea in a story because I think that if you try to nail things down too much, you’re not going to get very far - those choices that you make at the beginning, that’s all you’re going to discover, whereas what I try to do is constantly circle and see what surprises there are lurking in the subconscious pockets on the edge of the story. I constantly retell the story and I try and retell it quite inaccurately because I think the memory is a great guide, because the memory is also the psyche so you should also listen to what you remember inaccurately. I’m a great believer in error because that’s where you’ll discover what your retelling is about rather than honouring whatever is on the page which is ultimately why I don’t do plays. I find it almost impossible to stick to honouring what somebody else has written. I just constantly want to reinvent and retell.

But you did direct Cymbeline [a co-production with the RSC] even though you’ve said you don’t like or understand Shakespeare – which is quite a brave thing for a theatre director to say. I thought I did a genius job with Cymbeline (pictured right) - even though it was not well received critically, the audiences loved it. I just kept trying to retell that story, which is a mess – it’s a narrative bodge-job. So by retelling it and finding the sense and the links – we kept all of the heart of Cymbeline but we got rid of some of the confusion – we made some real sense out of a story which is really quite incomprehensible.

I thought I did a genius job with Cymbeline (pictured right) - even though it was not well received critically, the audiences loved it. I just kept trying to retell that story, which is a mess – it’s a narrative bodge-job. So by retelling it and finding the sense and the links – we kept all of the heart of Cymbeline but we got rid of some of the confusion – we made some real sense out of a story which is really quite incomprehensible.

It’s funny because I really thought we were going to be hailed as the company that had actually made sense of Cymbeline and of course we became known as the company that had destroyed this masterpiece! But I tell you what, we had young people understanding, enjoying, whistling through that show and I’d like to see a straight production of that play get that response.

When you first agreed to do it, were you at all daunted?

I’m never daunted by anything. I’m trying to teach myself to be a bit more savvy but it was the RSC who suggested it and that was good enough for me. It was pure, quite fairytaley. I always go into everything with a sort of terrible arrogance. I always think, I’m going to make this better. So no, I wasn’t daunted at all.

One of my greatest memories of Cymbeline was, having done what I think was a really clever job of making it accessible and beautiful and really believing in this piece of work and getting quite an extreme reaction – because there were audience members who walked out, people who were very insulted that it wasn’t true to the text, so we were getting strong reactions from individual members of the audience as well as the press – I remember walking to our van, which has Kneehigh written on the side of it, and seeing a big white thing on the windscreen and thinking, great, I’ve got a parking ticket, when it was actually a note from somebody saying, “Cymbeline is the most refreshing, the most brilliant, the most fantastic night out – fuck the critics,” and that carried on throughout the whole run. The van became like a notice board, people left notes for us on the van against the windscreen wipers and that was a beautiful thing to have happened.

How easy is it for Kneehigh to collaborate with other companies?

Each co-production is different, some are more successful than others. The RSC, I have to say, are brilliant in that they are very supportive but they don’t meddle.

A Matter of Life and Death caused a huge slanging match between Nicholas Hytner and certain critics. How did you feel about that?

Thank goodness for time, really. It was the most bruising, soul-destroying blow and slightly unfathomable. I’ve kind of made up a story I tell myself that helps but actually it was like being kicked when you’re down. I think that now, with some hindsight, I can identify some flaws in the adaptation and I think there are certain things that I wouldn’t repeat, but I knew then, as I know now, that there was some of the most beautiful, electric, inventive work in that show and yet it caused such an outrage with the critics – not the audience, we did over 90 per cent business over that run, maybe even 96 – and the level of anger they had… And again, if I replay it in my mind or, indeed, the very rare footage that we’ve got of it, it’s beautiful.

I was in a little bit of a hole at that point. Nick Hytner coming out and defending me was such an act of gallantry for which I’ll thank him forever, but the reality was that it gave the critics another chance to say, “No, we’re not dead white men, we just hate Emma Rice.” I only do this because I’m passionate and I want to entertain people and communicate with people and however much we say how exciting it is to be cutting edge, it’s not – it’s horrible. I don’t want hassle, I just want everybody to love the work and, more importantly, to get it, but they [the critics] seemed blind with rage, looking at that show – which was such a passionate, personal piece of work – and that is something I never will understand and I don’t wish to understand. (Pictured above: Douglas Hodge, Lindsey Marshal and Tristan Sturrock in A Matter of Life and Death.)

I was in a little bit of a hole at that point. Nick Hytner coming out and defending me was such an act of gallantry for which I’ll thank him forever, but the reality was that it gave the critics another chance to say, “No, we’re not dead white men, we just hate Emma Rice.” I only do this because I’m passionate and I want to entertain people and communicate with people and however much we say how exciting it is to be cutting edge, it’s not – it’s horrible. I don’t want hassle, I just want everybody to love the work and, more importantly, to get it, but they [the critics] seemed blind with rage, looking at that show – which was such a passionate, personal piece of work – and that is something I never will understand and I don’t wish to understand. (Pictured above: Douglas Hodge, Lindsey Marshal and Tristan Sturrock in A Matter of Life and Death.)

It’s entirely usual for plays to be adapted for the screen but that was the second film title you’ve staged and you’ve since adapted a third, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Have you always been interested in film or do you think that films translate well as pieces of theatre?

I think it just suits me – I’m not a film buff at all. The reality is, I was never very academic, I’ve only got two A levels, I certainly never read the classics but I did watch films at weekends. I think my psyche has more films in it than literature so the stories of my childhood come more from films than books. Now, had I read classics at Oxbridge, my psyche would be coming up with lots of other, more acceptable things. But I don’t really think it’s a choice, I’m just a storyteller and I have stories in my psyche which I’ve got from film which need to be told.

Brief Encounter took Kneehigh to a completely different level – to Broadway to be exact. Were you surprised by its success?

The hilarious thing about Brief Encounter is that it’s been the hardest slog ever and people say, “Isn’t it amazing, how it happened,” but it actually feels to me as if it’s been carved out of blood, sweat and tears, so I’m really pleased it did work because I’ve never worked so hard and so long in all my life. You never feel that you’re on a sky rocket - I always felt that I was pedalling hard up hill.

It was strange really, it was a bit like The Red Shoes. It was around the time of A Matter of Life and Death and I was demoralised. I felt very lost and didn’t know how to go forward because if your instinct is so heavily criticised, I don’t know what else to fall back on. But I had a meeting with David Pugh, the producer, and he asked if I was interested in doing Peter Pan and we had a long discussion about Peter Pan and at the end of it I said, “Thank you very much, I’m interested but not enough and I’m very busy and demoralised and it’s not the right time." I gave him a hug to say goodbye and over his shoulder I saw a shelf with DVDs on it and I saw, in the middle of them all, one title which was Brief Encounter. I don’t know why but I said as a passing shot, “If this meeting had been about Brief Encounter it would have gone very differently,” and he said, “Do you want to do it?” and I said, “Yes, I do,” and that’s what I did. Unbelievable – it came out of a really long, really detailed meeting about Peter Pan. It was another really instinctive moment, just like The Red Shoes. History has shown that it was a great marriage of my interest in film and a great text but there was also a lot of space around it for music and reimagining.

Did you know the film?

Yes, but only as a child. Until then I hadn’t watched it as an adult with intelligent eyes and it’s such a brilliant film. It lodges in your psyche somewhere and of course, what happens is – this is what I mean about the library of the psyche – I’ll have watched that one rainy Sunday afternoon and not understood it on a deeper level and years later you wake up with the knowledge that one has been unfaithful and one has a failed marriage and you go, “Oh God, yes - there’s some rich material that I understand."

Watch the trailer for Kneehigh's Brief Encounter

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg – now that’s billed as a Kneehigh production but Joanna Riding isn’t exactly a stalwart Kneehigh performer, is she?

No, none of that company were Kneehigh people because of the level of musicianship needed to deliver that score so it was an almost entirely new company.

So what made it a Kneehigh production?

Now there’s a question! Well, there are several things that come into it. There’s spirituality and the way in which I was allowed to create something on our own terms. I cast our shows and if anyone tries to interfere, there’s a problem, so I got to choose the cast I wanted. There’s the fact that I was there and that so much of my experience comes from Kneehigh, the creative team was nearly all Kneehigh but then there’s also the business side of things. To be completely frank, it wasn’t going to be a Kneehigh show but the producers asked us if it could be because our name was going to help sell tickets and we're no fools. But we thought long and hard about it and it wasn’t an easy decision to make – it was borderline, we would all say that. (Pictured below: Matt Wilman, Joanna Riding, Gareth Charlton and Aki Omoshaybi in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.)

So did you work in your usual way?

No, absolutely not. The score is completely fixed – it’s even more fixed than a play because you can’t even put a pause in. But life is long, there isn’t a Kneehigh way as such. We say at Kneehigh that we’re in it for the long haul which means we have to change and we have to try things out. I probably would do another musical again if it was the right one but I’ve come full circle because I’m back working in the barns devising work from scratch.

No, absolutely not. The score is completely fixed – it’s even more fixed than a play because you can’t even put a pause in. But life is long, there isn’t a Kneehigh way as such. We say at Kneehigh that we’re in it for the long haul which means we have to change and we have to try things out. I probably would do another musical again if it was the right one but I’ve come full circle because I’m back working in the barns devising work from scratch.

Did you find it easier, having that structure in place that you couldn’t stray from?

Yes, it made me think, oh, that’s why people direct musicals! I’ll probably get in trouble for saying this and obviously it didn’t always go smoothly, but on a good day you think, this is just staging, this is just the final bit of the work I normally do. I mean, it is very skilled but I did think, wow! This is the way forward!

So tell me about The Midnight Pumpkin and The Wild Bride.

Yeah, I think we just wanted to do something really enjoyable, it’s as simple as that. With all the different demands on us – and I have got aspirations to high art – but my basic aspiration is to have a good time so we wanted to create a show specifically for our Asylum tent [Kneehigh's portable theatre space] in which the audience participates, so The Midnight Pumpkin is a very light-on-its-feet idea. We’re not treating it like it’s Hamlet because it isn’t, but actually it’s fantastic, we’re having a ball. We’re crying with laughter all the time in rehearsals so fingers crossed we’re onto a winner.

The Wild Bride is very different. It’s storytelling and dance and blues music – I’ve never seen anything like it, although it does feel like going back to my roots a little bit. Actually The Wild Bride is all about a lifetime, it’s about endurance, it’s about how, even if you don’t think you’re going to survive something, you tend to wake up in the morning and you do. And it’s also about the bad bargains you make and I think it’s really good for me, I’m really enjoying exploring that, especially having been in the West End and having been on Broadway. It’s all about doing deals with the devil and I think, while I’m not saying that’s what it is, it’s great to come back home and just have a gentle toe in the water.

Would you say that Kneehigh is still a local theatre company?

Well, yes. We’re based here, we perform here. This is where we create work. At the moment our company members come from Cornwall, Hungary, Poland, Canada – it’s a very mixed bag, so are we all from here? No. But does the company have its roots in Cornwall? Yes.

- The Midnight Pumpkin, from 23 July to 7 August, 27 and 28 August, and The Wild Bride, from 11 to 26 August, at The Asylum, Tynarnhale Farm near Blackwater, Cornwall

- Visit Kneehigh's website

Watch a trailer for The Wild Bride

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Add comment