London Sinfonietta, Atherton, Queen Elizabeth Hall | reviews, news & interviews

London Sinfonietta, Atherton, Queen Elizabeth Hall

London Sinfonietta, Atherton, Queen Elizabeth Hall

Dutch master Louis Andriessen takes on Anais Nin and Plato

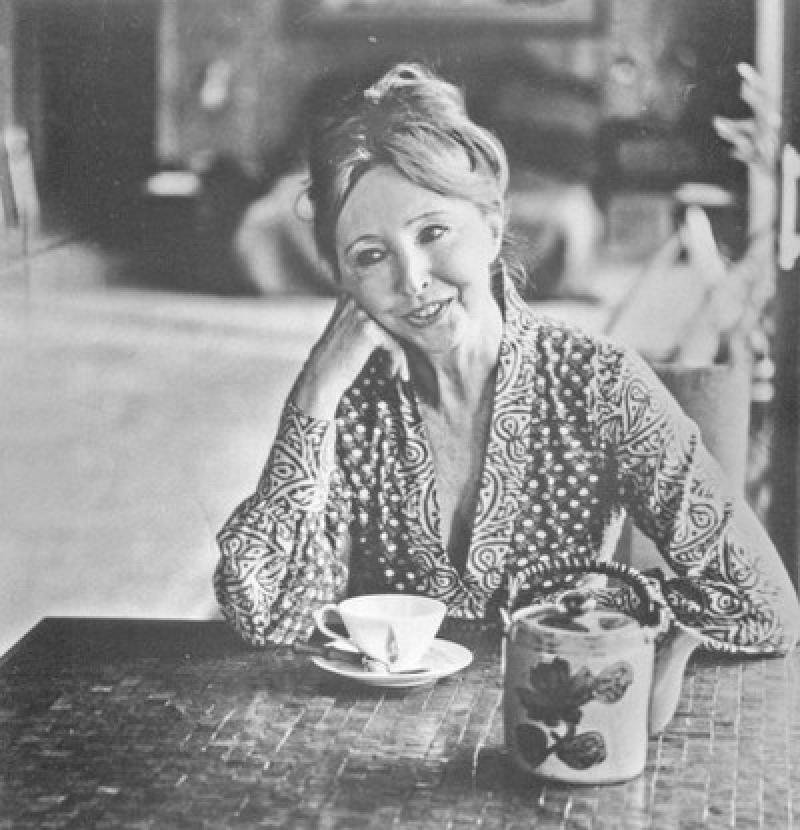

The most interesting thing about Louis Andriessen's musical snapshot of the famous eroticist Anaïs Nin - being given its UK premiere at the Queen Elizabeth Hall last night - was that the scene on the chaise longue in which Nin (Cristina Zavalloni) simulates riding her father was nowhere near the most unsettling episode.

The orchestral palette alone was something to behold: three electric guitars and two fat brass bands at its core, uncushioned but for a beefy portion of violas by strings. Classic Andriessen. Even our first hello was from an extraordinarily disputatious gaggle of squawking oboes and cor anglais. Anaïs Nin couldn't quite compete with that, though we could delight in its four saxes. And we did start with the sound of a kettle on the boil. A curious bit of domesticity in a musical monodrama about a woman whose biscuit of choice was screwing her father.

Sexual transgression was actually kept to a surprisingly suggestive minimum. Instead we got a rather subtle depiction of mental fucked-upness, in which a chamber orchestra, carefully made tranches of film (both controlled by Zavalloni's Nin) and chunks of texts from her and her four lovers (including one from a breathless Henry Miller) are brought into and out of focus in a seamless bit of Gesamtkunstwerk. The fact that neither film, theatre, music or singing tried to dominate one another - that each strand was allowed to drift in and out of consciousness - was in one way very clever. A better depiction of an interior world on stage I have rarely seen. But with each art form holding back slightly, there was also a feeling of being shortchanged.

The music had many fragrant snatches: pungent Eislerisms at the start, a recorded Poulencian salon song at the end, and soulful solo lines in between that were intermittently flung onto Bergian pyres of hysteria. But these small orgasms of forward development were padded out by long stretches of frustrated beginnings. And though you couldn't have asked for more from the freestyling Zavalloni - who is at once conductor, singer, actor, film-maker, kettle-boiler, mad cow, singing of whips and ecstasy and fucking her father, a real messy Gesamtkunstwerk on her own - I'm not sure one learnt a great deal from this glimpse into the interior life of "the sickest of all the Surrealists", as Nin described herself.

Learning came in the second half, with Andriessen's furious political disquisition, De Staat, which turns orchestra into a public forum. Using 27 amplified instruments, the language of Stravinsky and bebop, Andriessen examines several ways of social organisation through orchestral means, from melodic oligarchies to polyphonic democracies. Four female singers (the ever excellent Synergy Vocals) offer up Plato's thoughts on music and morality from The Republic. The result is a raucous canonical discussion from opposing brass bands, who finally come together in a fire-breathing slapdown of Platonic authoritarianism that is in itself suggestive of a new oppressiveness. The virtuosic London Sinfonietta, under the cool mastery of conductor David Atherton, played the work hard and fast, and delivered a Paxman-esque final showdown.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Add comment