127 Hours | reviews, news & interviews

127 Hours

127 Hours

Danny Boyle's latest is visceral film-making which leaves no lasting impression

Made with the same furious energy which has characterised so much of Danny Boyle’s output, 127 Hours goes from the macro to the micro. It opens with a pounding split-screen assault of imagery depicting the frenetic, dehumanising nature of modern life, before closing in on one man’s five-day ordeal in a crack in the earth.

Aron Ralston (James Franco) is a young, cavalier adventurer, full of pluck and derring-do. As the film begins he is hurriedly packing for his latest one-man adventure – canyoning near Moab, Utah - blissfully ignorant of how his slapdash preparations will cost him dear. Portentously neglecting to tell anyone where he’s going, his safety is further compromised when he fails to find his sharp penknife. The folly of this seemingly innocuous omission is brought to our attention by a slyly positioned camera - situated almost tauntingly at the back of a cupboard as he gropes blindly – showing us that the much-needed object is sitting just out of reach. It’s an ominous image, the disproportionate ramifications of which will be revealed later in the film. At this point, given the focus on head-smacking errors and a sense of impending catastrophe, it’s hard not to draw comparisons with the BBC's Casualty, although this is perhaps a little unfair.

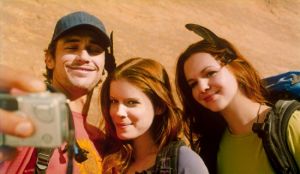

As he bounds exuberantly and arrogantly about the wilderness, Ralston is shown as a man so at ease with his environment that he is missing a sense of caution, or of his own vulnerability. He positively, even irritatingly, boils over with bravado, managing some outrageous flirting alongside feats of daring when he runs into two inexperienced but game female backpackers. As Kristi and Megan (Kate Mara and Amber Tamblyn, pictured below right with Franco) head off on their own adventure, things are left on a promising note as they invite him to a party, with a future hook-up seemingly inevitable.

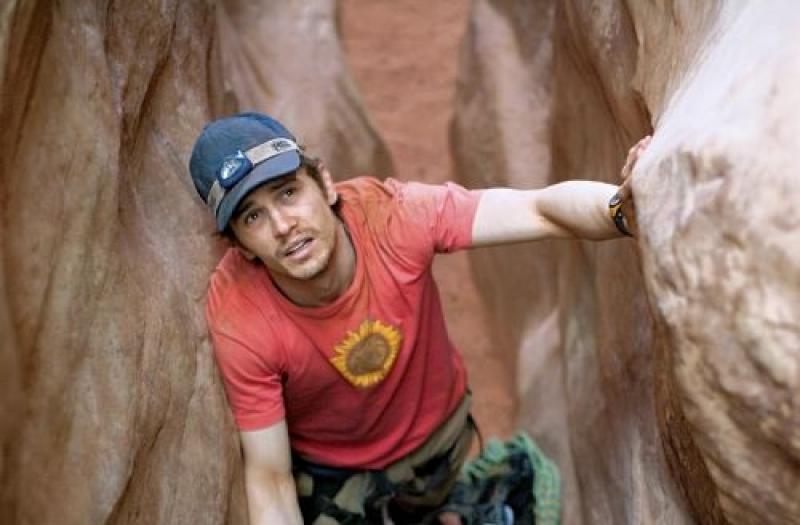

Shortly after the girls depart (but long enough so that they are undoubtedly out of earshot) disaster strikes and Ralston finds himself pinned by an immovable rock in an isolated canyon. And so the titular 127 hours begin. To illustrate the predicament, it is at this moment that the film’s title wittily (and almost too irreverently) appears, slap-bang on the very rock that pins him fast. If this is man versus nature, nature has played its hand very well indeed.

Shortly after the girls depart (but long enough so that they are undoubtedly out of earshot) disaster strikes and Ralston finds himself pinned by an immovable rock in an isolated canyon. And so the titular 127 hours begin. To illustrate the predicament, it is at this moment that the film’s title wittily (and almost too irreverently) appears, slap-bang on the very rock that pins him fast. If this is man versus nature, nature has played its hand very well indeed.

The ever-restless camera, which at first captured the boundless energy of this extreme sports junkie, now channels the hallucinogenic hysteria and utter desperation of Ralston’s terrible predicament. The pace and scale of the opening is seamlessly substituted for a magnified, against-the-clock urgency, as Ralston fights for his freedom and struggles to maintain a grip on his sanity. His immobility is ingeniously overcome by the film’s forays into fantasy, back-story and psychological illumination. Boyle (for whom this was something of a vanity project) achieves wonders with an - on paper at least - unpromising story, working from a bulging bag of stylistic tricks. Considering its limited location and predominantly single-character focus, it is testament to his formidable talent as a film-maker that he maintains interest throughout. Franco gives a compelling turn, particularly impressive bearing in mind that Ralston, as depicted here, is something of a "Marmite" character – both heroic outdoorsman and gratingly self-absorbed hedonist.

The film's denouement - in which Ralston amputates his arm with a blunt penknife - is of course common knowledge. The squeamish may struggle with the sequence which, although hardly boundary-pushing in its ghastliness, is rendered all the more excruciating by Franco’s remarkably believable anguish.

Transcending the limitations of the source material, Danny Boyle’s much-anticipated follow-up to awards-magnet Slumdog Millionaire is an irrepressible interpretation of a torturous true-life tale. Although it fails to reach the dizzyingly enjoyable heights of his earliest work (Shallow Grave, Trainspotting) – largely due to its lack of scope, plot and charismatic characters – it is accomplished, ingenious film-making nevertheless. A credible realisation of an unfortunate predicament, 127 Hours is cinema as a visceral experience, forcing its audience to endure the confines and anguish of Ralston’s ordeal. It’s a film that commands a lot of respect, though it seems unlikely - once it releases you back into the light - that it will linger in the memory of many.

Watch the trailer for 127 Hours

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment