Jonathan Burrows & Matteo Fargion, Cow Piece/ Akram Khan, Vertical Road, Sadler's Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Jonathan Burrows & Matteo Fargion, Cow Piece/ Akram Khan, Vertical Road, Sadler's Wells

Jonathan Burrows & Matteo Fargion, Cow Piece/ Akram Khan, Vertical Road, Sadler's Wells

Opposite ends of theatre - spectacular melodrama, sidesplitting comedy

The annual Dance Umbrella festival is mostly for the dance industry to talk to itself, I’ve come to feel, with a timetable so closely packed that only Londoners, and specifically those in the tight roaring circle of the know, will get to sample much of it. Then you get two such stand-out evenings as Akram Khan’s and Jonathan Burrows’ in town within a week of each other, two of the major talents in the world, who come running at the idea of theatre from opposite ends - the one spectacular and melodramatic, the other offbeat, mischievous stand-up dance-comedy.

Given that there is a large border of pretentiousness along Khan’s Vertical Road - he does like to let one know that dance is a holy art and he is its priest - I would plump for the frying my brain got last night from Burrows and his partner Matteo Fargion as the night I’m most delighted to have come across.

It’s hard to believe that Burrows was once a major Royal Ballet artist, on the character side, because his choreography so rapidly abandoned the conventions of ballet (actually I don’t remember his works having much about ballet except a whiff of its fluidity in certain windblown whirls and lifts). It travelled for a while towards the William Forsythe school of almost scientifically fascinating movement, broken up and examined in masterpieces like Our and The Stop Quartet, before stopping - and we were left Burrows-less for a long, worrying while. Then it returned 10 years ago, wholly unpredictably, in an odd duet with a Dutchman in which Burrows started talking. After that, there was no stopping him.

He found a new co-worker, the composer Matteo Fargion, and they made three startling and hilarious duets, examining rhythm from all sorts of angles, applying speech like an abstract percussive instrument to stumbling little dances, patting, whistling, yelping, seriously eccentric amusements. And they are back this week for three precious days, with an hour’s entertainment that continues the trilogy’s ideas in the funniest, richest, most life-enhancing evening I’ve had at anything associated with the “dance” label this year (probably since their last one).

He found a new co-worker, the composer Matteo Fargion, and they made three startling and hilarious duets, examining rhythm from all sorts of angles, applying speech like an abstract percussive instrument to stumbling little dances, patting, whistling, yelping, seriously eccentric amusements. And they are back this week for three precious days, with an hour’s entertainment that continues the trilogy’s ideas in the funniest, richest, most life-enhancing evening I’ve had at anything associated with the “dance” label this year (probably since their last one).

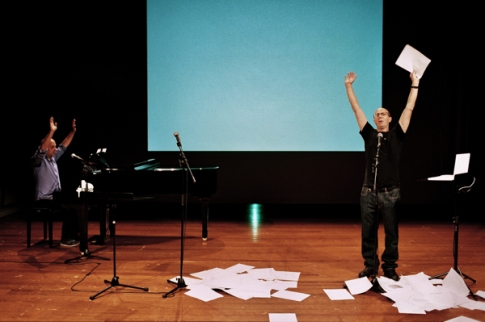

Part one, Cheap Lecture (pictured right, by Herman Sorgeloos), is a cheeky tribute to John Cage and the happenings that bust open ideas about dance in American theatre in the early 1950s. It is a delightfully crazed dual lecture, playing off one character against the other (lugubrious clown Fargion, perky professorial Burrows), just as surely as it plays the natural rhythms that give sentences meaning off against insistently different and sometimes warring rhythms. This is not, as they admit, a new idea. One of their lines is: “We don’t know what we’re doing, but we’re doing it - [shrug] - everything is stolen anyway.”

They make their thefts clear in their script, no less funny for that. The lines jibe at the con-trick that performers play against their audience by feeding the audience’s willingness to believe in them (no matter how vacant the performers are feeling). Yet when the lines are fractured by “wrong” rhythms (rather like Shakespeare’s Mechanicals in "Pyramus and Thisbe" in A Midsummer Night’s Dream), words become mad lost creatures looking to join up with others and acquire a meaning in the gap. This sounds too serious. but it’s the serene intellectual curiosity underlying even the cheapest gags that makes this so enjoyable a Cageian homage.

One has known about the imminent cows all along, as there are 12 little plastic Friesians lined cutely up on the tables behind the pair in the first part; but the uproarious use of them in Cow Piece is an explosively funny surprise. Like competing costermongers, Burrows and Fargion demonstrate their toy cows, creating tight little suspense dramas about their fates - some of them gruesome - snatching up musical instruments, a ukulele, a harmonica, a modest little squeezebox, an accordion, a piano, and dragging poor Schubert in there somehow.

Fargion lards it lavishly with Italian capriciousness, strumming Neapolitan ditties, blowing a football ref's whistle and pointing accusingly between two guilty plastic cows, “Wasn’t me”, “Wasn’t me”, or crying “Muoio! Muoio!” ("I'm dying") like Scarpia in Tosca while Burrows cuts a caper. Burrows, who’s a brilliant music-hall stooge, counters with a mock-Victorian song about a baby that meets an unfortunate end. How do they notate such complex interlockings of gesture, sound, word, props and movement, allying logic ad absurdam with subconscious association-games? How long does it take them to create this diabolical puzzle? Never mind - just please go and see this tonight or tomorrow. It could be years before they’re back.

We see a lot of Akram Khan, on the other hand, and I confess I have felt a little stifled by the pretentiousness in a couple of his recent pieces, when he puts telling us about his spiritual journey ahead of the magnificently individual dance language he is copiously able to deliver. But his new creation, Vertical Road, struck me for half its length as refreshingly angry and direct, the work of a man who instead of telling us all the answers, is confident enough to start asking them again.

The exceptional opening section tells of the fearfulness of birth, with a man isolated from others by a transparent membrane, while on the other side a group of dancers in white pound out a frightening martial routine of jabbed elbows and swift evasive feints in a storm of talcum powder. The force of the motion is unusually vivid, each knotted or scything arm having a bunch of finely delineated kathak fingers at the end, like handfuls of blades. The seven appear like people possessed, dancing in a lacerating ritual directed inwards at themselves. It is magnetic dancing-as-metaphor, the powder like a dust of time thrown off by people long buried, wondering why they allow themselves to be dead.

The exceptional opening section tells of the fearfulness of birth, with a man isolated from others by a transparent membrane, while on the other side a group of dancers in white pound out a frightening martial routine of jabbed elbows and swift evasive feints in a storm of talcum powder. The force of the motion is unusually vivid, each knotted or scything arm having a bunch of finely delineated kathak fingers at the end, like handfuls of blades. The seven appear like people possessed, dancing in a lacerating ritual directed inwards at themselves. It is magnetic dancing-as-metaphor, the powder like a dust of time thrown off by people long buried, wondering why they allow themselves to be dead.

The lone man sets off some sort of universal tick-tocking clock, arranging a henge of seven small black tablets in a row, like tombstones. An elegantly theatrical symbol, and giving the bare stage a strong little focus at the front around which Jesper Kongshaug’s wizard, arctic lighting makes dramas of diagonal beams, night and day.

Nitin Sawhney is Akram’s regular music collaborator, but as too often before with their pieces together the score’s inflated seeking after effect puts a big bland blanket over choreography that contrarily asks your eyes to home in on small, distilled details. The din of electronic beats was shattering on Thursday night. Why does Sadler’s Wells do this to our hearing? I resent having my ears belaboured for no good reason. Elsewhere the music has more sense of presence, more openness to choreographic suggestion, when it feels more Asian, and the instrumentation adopts free Indian vocal rhythms rather than rigid electronic pulses.

The Akram-Sawhney partnership moves predictably through stages of self-discovery, from birth to irresolute uncertainty, to an earthier, rootsier mode, before an apotheosis of explosions, lightning and enlightenment for the lone man walking off into essential loneliness - cue sad music. Spectacular it often is, direct and exciting too, but Akram loves to lecture his public about his personal journey, and finally it doesn’t, for me, escape a deflating whiff of bathos.

- Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion are at Sadler's Wells' Lilian Baylis Studio, London till tomorrow

- Burrows performs with Chrysa Parkinson in Dogheart (a work with animated drawings) at The Place, London, 25 & 26 Oct

- Dance Umbrella runs in various London venues until 30 October - more information about all events on its website

- Akram Khan's website has Vertical Road's touring itinerary, including (after a week in Melbourne, Australia) Brighton's Dome, 28 Oct; Koln's Schauspielhaus 11 & 12 Nov; Swansea's Taliesin Arts Centre, 15 & 16 Nov; Snape Maltings Concert Hall, 19 & 20 Nov; Bolzano's Fondazione Teatro Comunale, 24 Nov; Antwerp's DeSingel, 2-4 Dec

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Comments

...