Halloween Special: Patrick McGrath on Sheridan Le Fanu's horror stories | reviews, news & interviews

Halloween Special: Patrick McGrath on Sheridan Le Fanu's horror stories

Halloween Special: Patrick McGrath on Sheridan Le Fanu's horror stories

The modern Gothic novelist pays tribute to an Irish 19th-century master of the scary tale

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, son of a Protestant clergyman and grand-nephew of the playwright Sheridan, was born in Dublin in 1814. He spent part of his boyhood in County Limerick, where from local storytellers he heard legends of fairies and demons. Later he became a journalist. For some years he was proprietor and editor of the Dublin University Magazine, a conservative publication that spoke for the Protestant ruling class in Ireland, also known as the Ascendancy.

Of the five stories collected here [in the Folio Society's new edition of In a Glass Darkly: Haunting Tales for Halloween], Green Tea is the least voluptuous. It is a dry and darkly comic tale about a vicar, the Rev Mr Jennings, a scholarly gentleman who lives alone in London, “where, in a dark street off Piccadilly, he inhabits a very narrow house”. A tall thin man, then, in a very narrow house, who, when he writes a note to our narrator, Dr Martin Hesselius, does so “with a very sharp and fine pencil”. Like Hesselius, and like Le Fanu himself, the vicar is a student of Emanuel Swedenborg, the philosopher and visionary who believed that there exists a world of spirits, good and evil, that interpenetrates our own world. Mr Jennings has sought the help of Hesselius, a doctor of “metaphysical medicine”, because his life has become intolerable to him. He is haunted by a small black monkey that has no objective existence.

Hesselius proves on closer inspection to be as grossly unreliable a doctor as he is a narrator

He encounters it first on a London bus on a dark night, where he sees its red eyes glittering in the shadows. Attempting to prod it with his umbrella, he discovers to his horror that the umbrella passes right through the creature. The monkey has only one peculiarity, aside from its immateriality: its “unfathomable malignity”. It haunts the vicar, interrupting his prayers with “dreadful blasphemies”. It finally drives him to suicide.

A simple story on the face of it, but complicated by the presence of Hesselius, who proves on closer inspection to be as grossly unreliable a doctor as he is a narrator. The story has a prologue written by his unnamed medical secretary, who has selected this case from the doctor’s copious correspondence with his friend, Professor Van Loo of Leyden. The unfortunate vicar, his story buried within these various documentary frames, is no less smothered by Hesselius’s pseudoscientific hocus pocus, particularly his pronouncements on the nervous fluid. But Hesselius cannot stand by his own diagnostic convictions. He hedges his bets, suggesting that the vicar’s complaint may simply be a case of “hereditary suicidal mania”, or even the result of drinking too much green tea. Hesselius is a charlatan, and the joke is in the spurious accounts he gives of what ails his patients. He is also clinically, even fatally, irresponsible. For having told the Rev Mr Jennings that, should the monkey reappear, he is to be sent for, he then goes to an inn to consider the case. Not wishing to be distracted, he tells nobody of his whereabouts. It’s while he’s thus sequestered that the vicar kills himself.

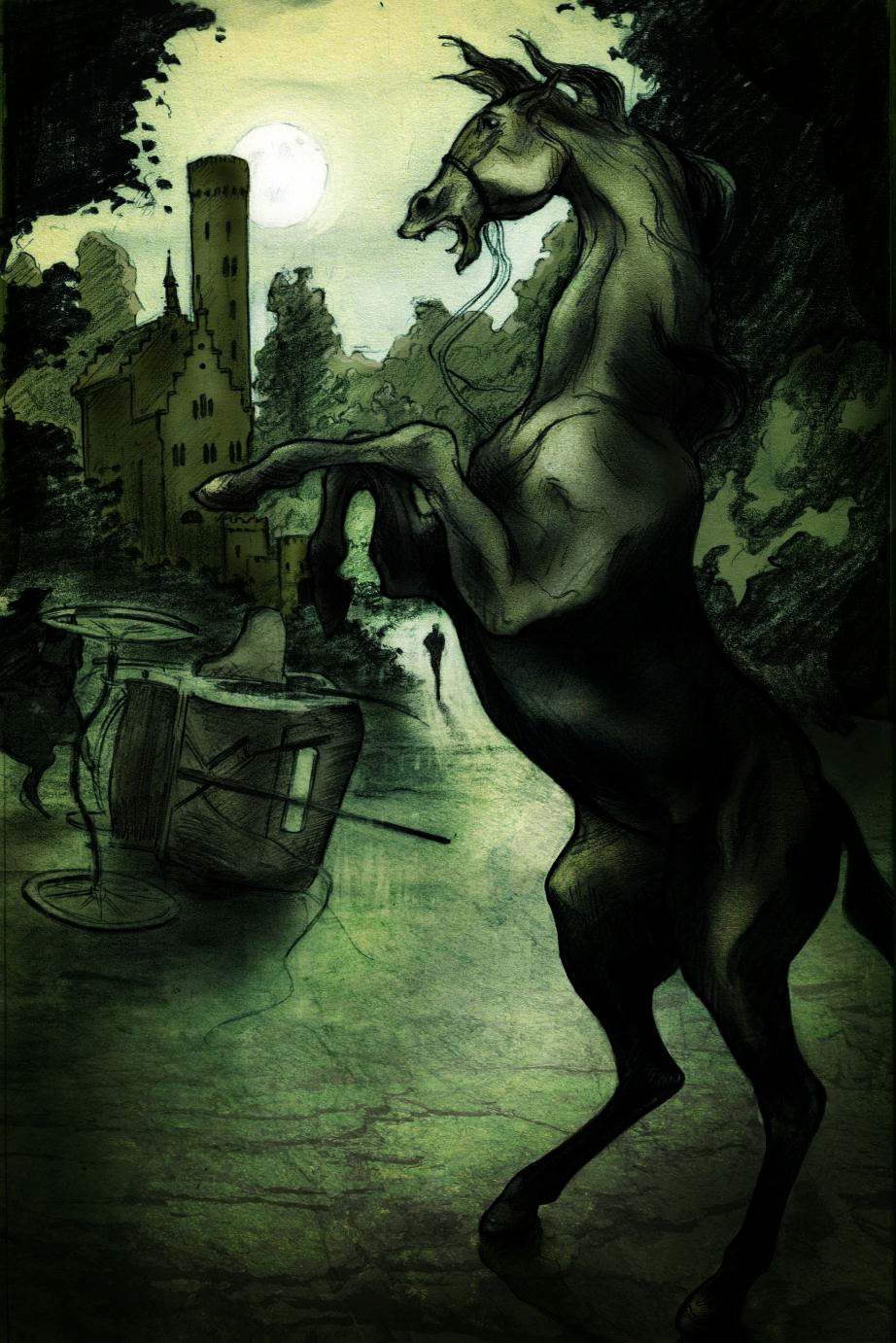

VS Pritchett found Le Fanu’s phantoms frightening because “they can be justified: blobs of the unconscious that have floated up to the surface of the mind... not perambulatory figments of family history, moaning and clanking about in fancy dress”. * Another blob from the unconscious manifests in The Familiar, which is also taken from Hesselius’s secretary’s archive of cases “more or less nearly akin to that I have entitled Green Tea”. It resembles that story in some respects. It involves a naval commander named Barton who one night hears footsteps dogging him. But when he turns there’s nobody there. Some days later a shrunken man, mad and evil in appearance, confronts the brave captain and terrifies him. From that point on he’s a haunted man, and a doomed man.

VS Pritchett found Le Fanu’s phantoms frightening because “they can be justified: blobs of the unconscious that have floated up to the surface of the mind... not perambulatory figments of family history, moaning and clanking about in fancy dress”. * Another blob from the unconscious manifests in The Familiar, which is also taken from Hesselius’s secretary’s archive of cases “more or less nearly akin to that I have entitled Green Tea”. It resembles that story in some respects. It involves a naval commander named Barton who one night hears footsteps dogging him. But when he turns there’s nobody there. Some days later a shrunken man, mad and evil in appearance, confronts the brave captain and terrifies him. From that point on he’s a haunted man, and a doomed man.

But unlike the events described in Green Tea, the story of Captain Barton is ultimately shown to have an explanation of sorts. The blob of the unconscious, in the form of the evil little man, arises from events that occurred early in the captain’s career. The guilt attaching to those repressed events has evidently returned with a vengeance to wreak havoc on the captain. Doctor Hesselius was not directly involved in the case of Captain Barton, but he has no doubt that, had he been consulted, “I should have without difficulty referred those phenomena to their proper disease. My diagnosis is now, necessarily, conjectural.”

They come to place me in the grave alive; save me

The medical secretary remarks: “Thus writes Doctor Hesselius; and adds a great deal which is of interest only to a scientific physician.” The doctor of metaphysical medicine is less in evidence in the remaining stories in the collection. In the prologue to Mr Justice Harbottle he is seen to be making a muddle with his papers, having apparently lost one of the two accounts of the judge’s story, and having then forgotten that the man to whom he had lent it had in fact returned it. All this the faithful secretary duly records.

Le Fanu here creates an even more elaborate frame for his story. He opens with one Mr Harman, author of the surviving account of the case, who has business with a familiar Le Fanuvian figure, “a dry, sad, quiet man, who had known better days... No better authority could be imagined for a ghost story”. Late one night the dry quiet man sees two figures emerging from his closet, dressed like characters just stepped out of a Hogarth print. One of them is carrying a coil of rope.

The dry quiet man tells Mr Harman what has happened. Mr Harman then writes to an old friend “living in a remote part of England”, who knows exactly who the ghosts are, and proceeds to tell the story. The reader, to reach this narrator, has in less than four pages been passed from the late Doctor Hesselius to his secretary, thence to Mr Harman, from him to the dry sad man, from the dry sad man back to Mr Harman, and from Mr Harman to the old man living in a remote part of England. And the chain of narrating personages doesn’t end there; for it’s the father of the old man from the remote part of England who, as a boy, actually saw Judge Harbottle on the bench, and knew his reputation as “about the wickedest man in England”.

Characters from the judge’s past, some of whom he sent to the gallows, or to jail, where they died, will now arise to torment this awful man and serve him a dose of his own forensic medicine.

What is Le Fanu up to here? Indulging, one guesses, his robust scepticism that any claim to truth that has passed through a world of men and women could possess even a shred of plausibility, for in its progress it will have come to resemble nothing so much as a ghost story. But a very good ghost story, in which, for example, a hangman is observed on top of a gigantic three-sided gallows, “reclining at his ease and listlessly shying bones, from a little heap at his elbow, at the skeletons that hung round, bringing down now a rib or two, now a hand, now half a leg”.

What is Le Fanu up to here? Indulging, one guesses, his robust scepticism that any claim to truth that has passed through a world of men and women could possess even a shred of plausibility, for in its progress it will have come to resemble nothing so much as a ghost story. But a very good ghost story, in which, for example, a hangman is observed on top of a gigantic three-sided gallows, “reclining at his ease and listlessly shying bones, from a little heap at his elbow, at the skeletons that hung round, bringing down now a rib or two, now a hand, now half a leg”.

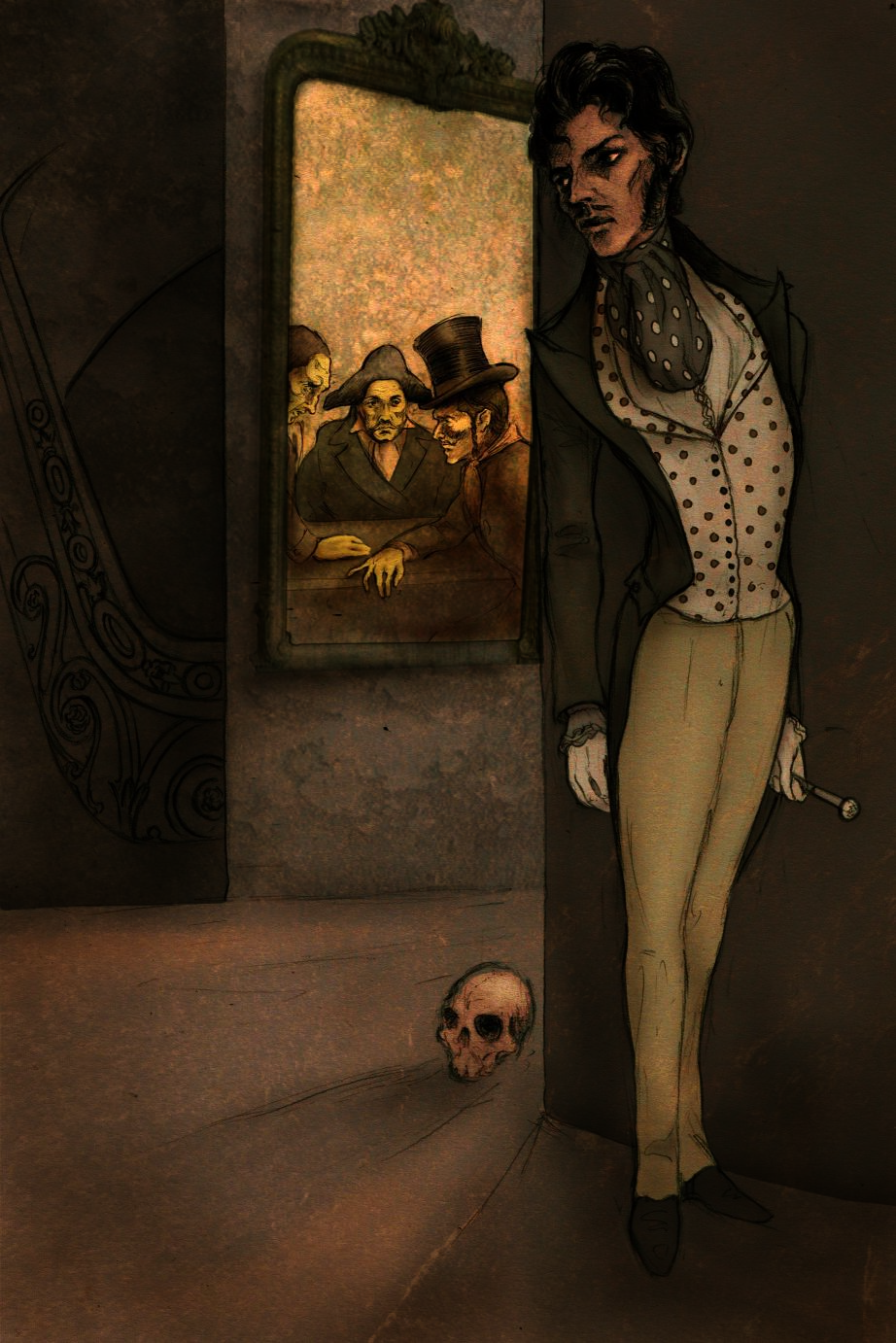

In terms of the voluptuousness Elizabeth Bowen found in Le Fanu, the collection grows warmer as it advances. A long story, The Room in the Dragon Volant, is driven by a dandyish young Englishman’s eager desire for a sexual adventure. Richard Beckett, age 23, is en route from Brussels to Paris in 1815, after Napoleon’s recent defeat at Waterloo. He has “an unfathomable purse”, having inherited a considerable fortune. Sexual adventure soon offers itself: a beautiful woman, in the company of an old man, is encountered in difficulty on the highway. Beckett comes to the rescue and is soon in love.

The plot thickens briskly as Beckett pursues the woman, distracted only briefly by a dream in which he sees her lying on a catafalque in a Gothic cathedral, apparently about to be interred, until she says, without stirring: “They come to place me in the grave alive; save me.” Thus does Le Fanu announce the great and terrible idea that so appalled and fascinated the 19th century: premature burial.

There follows a long build to a dramatic denouement involving a locked-room mystery, an elaborate ruse, a drug that induces cataleptic paralysis, and a coffin. There is nothing of the supernatural in this story. All that seems so is explained, including the various corpses impersonating the living, and all of the living who impersonate the dead. There is tremendous narrative momentum; a rich, colourful cast of characters, including the gasconading Colonel Gaillarde, who claims to have ichor and not blood in his veins; and a supremely well-organised plot, the secrets of which are not revealed until the very last pages.

Le Fanu leaves us in no doubt as to the erotic nature of the relationship

Carmilla is justly celebrated as one of the greatest vampire stories ever written, surpassed only by Dracula, which came out some 20 years later, the work of Bram Stoker, another Protestant Gothic novelist from Dublin. Apparently Doctor Hesselius once wrote an essay on the subject of vampirism - "with his usual learning and acumen, and with remarkable directness and condensation” - but his secretary won’t present it to us: “I shall forestall the intelligent lady, who relates [this account], in nothing,” he declares. The intelligent lady is Laura, a victim of the vampire Carmilla, who survived to relate her tale.

She lives with her father and various retainers in a small castle in a remote part of Austria. Nearby are to be found remnants of the ancient and extinct Karnstein family. The ruins of their castle are there, also a ruined village and a chapel with mouldering tombs in the aisle. The story begins with an accident involving a carriage, and the emergence from that carriage of a beautiful young woman. She is unconscious, and is carried into the castle to be cared for. Thus does the vampire cross the threshold and enter the home.

From the start Carmilla’s relationship with Laura is one of tender physical intimacy. “She used to place her pretty arms about my neck, draw me to her, and laying her cheek to mine, murmur with her lips near my ear...” There are many trembling embraces and soft kisses, and Le Fanu leaves us in no doubt as to the erotic nature of the relationship. He writes of “certain emotional scenes, those in which our passions have been most wildly and terribly roused”; of Carmilla’s “languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell... It was like the ardour of a lover... her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, 'You are mine, you shall be mine.'”

At other times Carmilla is languid and melancholy. She comes down very late in the morning. She tires easily. Meanwhile, young women in the neighbourhood are growing sick and dying. One night Laura sees a monstrous black animal in her room. It springs onto her bed. She feels a stinging pain, as though needles have been thrust into her breast, and awakens with a scream. A woman in black stands at the foot of her bed. Without appearing to move she changes position. She is close to the door. Then she is out of the room. Laura runs to the door: it’s still locked on the inside.

At other times Carmilla is languid and melancholy. She comes down very late in the morning. She tires easily. Meanwhile, young women in the neighbourhood are growing sick and dying. One night Laura sees a monstrous black animal in her room. It springs onto her bed. She feels a stinging pain, as though needles have been thrust into her breast, and awakens with a scream. A woman in black stands at the foot of her bed. Without appearing to move she changes position. She is close to the door. Then she is out of the room. Laura runs to the door: it’s still locked on the inside.

Laura feels a deep lassitude in the days that follow. She has dim thoughts of death. She dreams of her throat being kissed. She grows pale but won’t admit that she’s ill. She dreams of Carmilla in a white nightdress covered in blood. She wakes in panic and rushes to Carmilla’s room. It’s locked, and there’s no answer to her knocking. But when the door is forced the room is empty.

Suspicions are aroused; the truth about the sick and dying girls is guessed at. But it takes an antiquarian of peculiar talents to locate Carmilla’s tomb in the Karnstein chapel. She was buried 150 years earlier, but there she lies in seven inches of blood with a “faint but appreciable respiration”; “no cadaverous smell exhaled from the coffin". A sharp stake is driven through her heart and a piercing shriek is heard. The head is cut off and burned with the body, and the ashes are thrown in the river.

It was Le Fanu’s genius to embed these terrors in stories of haunted men and violated girls

In conclusion we are given this intriguing psychological insight: “The vampire is prone to be fascinated with an engrossing vehemence, resembling the passion of love, by particular persons... It will never desist until it has satiated its passion.” It will “husband and protract its murderous enjoyment with the refinement of an epicure, and heighten it by the gradual approaches of an artful courtship. In these cases it seems to yearn for something like sympathy and consent.”

As with much of Le Fanu’s fiction, “Carmilla” has been read as an expression of the profound unease of the old Anglo-Irish Ascendancy in the mid-1800s. It manifests the nightmare of a ruling class which dreads that those it has subjugated will rise and tear it down. These fears were not unfounded: in Le Fanu’s day the Catholic population of Ireland was already in the process of displacing its rulers, and the writing was very clearly on the wall. It was Le Fanu’s genius to embed these terrors in stories of haunted men and violated girls, and through their various transactions with phantoms and monsters shed light on tainted histories and guilty souls. Sheridan Le Fanu, reclusive, anxious and reactionary, confronted his fears of class annihilation and turned them into high Gothic art.

* Elizabeth Bowen, introduction to Uncle Silas (The Cresset Press, 1947)

* Quoted in Roy Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch (Penguin Books, 1995)

- In a Glass Darkly: Haunting Tales for Halloween by Sheridan Le Fanu with an introduction by Patrick McGrath and illustrations by Finn Campbell-Notman is is available from www.foliosociety.co.uk or by telephone on 0207 400 4200 or at The Folio Society Bookshop, 44 Eagle Street, London WC1R 4FS

Watch the dream sequence from Charles Frank's 1947 film version of Uncle Silas

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

Add comment