Leiferkus, LPO, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Leiferkus, LPO, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall

Leiferkus, LPO, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall

A voyage around Musorgsky: from the raw original to more recent composers' homages

How odd that Musorgsky, a composer sanctified beyond his very individual deserts for making social statements in his art, should be feted by an orchestra, or rather an orchestral management, which says music and politics don't mix.

At any rate, total engagement of a non-political nature was what held Vladimir Jurowski's latest "only connect" programme together as it ranged from that most unorthodox of Russians to two contemporary figures inspired by him - one orchestrating to serve the master, the other much more for himself, both also heard as their thorny, embattled selves.

We do need to get beyond the circumstances first, and it's sad that in practical terms there's no sign of that happening as I write. It struck me as unhelpful to meet blacklisting for a boycott with another boycott, but the question I'd already asked the management still needs answering. It was right of the LPO to caution with maximum publicity the four players who put their signatures to a newspaper letter protesting the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra's visit to the Proms - if indeed they added the orchestra's name to their own (who actually did this remains unclear). It was emphatically wrong to suspend them first for nine months and then for six (some concession). Until clemency is extended and the ban rescinded, the LPO's reputation will suffer as much as the exiled players.

All process and atmosphere, Zimmermann's shorter mood pieces shouldn't work so well, but like Ligeti's, they're mesmerising

Yet of this there was not so much as a murmur last night. Which was a relief as far as the extreme concentration of the music-making went. Musorgsky in his wild, undisciplined early maturity came first with a thrash through the original Night on a Bare Mountain (strictly we ought to call it by that initial name, St John's Night on the Bare Mountain). Rimsky-Korsakov, for once, was right in shoehorning the cloven hooves of a later version into his much more organic showpiece. Though Jurowski made the orchestra burn with focused fire from the very first, lurid notes, even he couldn't persuade us that Musorgsky's stop-start technique is all intuitive genius.

Still, it's fascinating to hear echoes of the dainty flickers around Wagner's dallying minstrel Tannhäuser in Venusberg - an influence missing from the familiar arrangement - and the rampaging of the supernatural whole-tone scale just when our maverick composer seems to have given up on finding a place to stop.

Mental drift would be hard for even the most determined listener to stave off both here and in the most obvious of the evening's homages, the world premiere of Alexander Raskatov's A White Night's Dream. We needed to hear what Raskatov is capable of beyond the demands of edgy music-theatre (and I seem to have been one of the few who came to admire his score for the Bulgakov opera A Dog's Heart at English National Opera last season). Stripped of any perceptible illustrative quality, what we get is the same collage of extreme-frequency sounds, with some extra-terrestrial writing for trombones, frozen as a snapshot of portentous, toppling carnival floats.

Raskatov's hothouse eclecticism is the opposite of the hypnotic concentration in Bernd Alois Zimmermann's Stille und Umkehr (Silence and Return). A side-drum sporadically taps out a rhythm - Schubert? Blues? - against shifting colours on a single note. All process and atmosphere, Zimmermann's shorter mood pieces shouldn't work so well, but like Ligeti's, they're mesmerising, especially when the rhythms and the colours meet as perfectly as they did in Jurowski's supremely well-controlled performance.

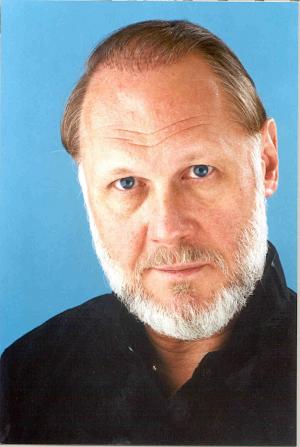

The rest was unique programme-building, but much less of the essence. In short, Zimmermann effaces every aspect of his own personality except for the fastidious textures in his arrangements of two evocative but small-beer Musorgsky piano pieces, while Raskatov says "here I am" at length when he dares to follow Shostakovich in orchestrating the Songs and Dances of Death. It's endemic of his approach that you stop watching and listening to even as charismatic a baritone - I'm always tempted to say "bass baritone" - as Sergei Leiferkus (pictured right) and fixate instead on the gluey but often outlandish instrumental linings.

The rest was unique programme-building, but much less of the essence. In short, Zimmermann effaces every aspect of his own personality except for the fastidious textures in his arrangements of two evocative but small-beer Musorgsky piano pieces, while Raskatov says "here I am" at length when he dares to follow Shostakovich in orchestrating the Songs and Dances of Death. It's endemic of his approach that you stop watching and listening to even as charismatic a baritone - I'm always tempted to say "bass baritone" - as Sergei Leiferkus (pictured right) and fixate instead on the gluey but often outlandish instrumental linings.

Perverse as Raskatov may be to give Musorgsky's opening meanderings to celesta and harpsichord, it was hard not to admire the originality of brass glissandi following the voice as Death lullabies the sick child to eternal rest in the first song, or the electric guitars that join the serenade of the macabre oily lover, another of Raskatov's favourite homages to early Schnittke.

But even stalwart veteran Leiferkus - on good form now after an apparent decline - couldn't be heard as Death the Field Marshal, smothered by oddly co-ordinated orchestral cohorts. Did the arranger think of giving his soloist a microphone? And those endless interludes of pure Raskatov with one arch homage to the coronation bells of Boris Godunov: now what was all that about? Shostakovich wanted his death-dirge Fifteenth Quartet played "so that flies drop dead in mid-air, and the audience start leaving the hall from sheer boredom" - but he meant that in a good way, as Raskatov with his rambling interventions seemingly does not.

So thanks, Jurowski, for another inimitable programme that few other conductors could get away with, but next, please.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Add comment