LSO, Davis, Uchida, Barbican Hall | reviews, news & interviews

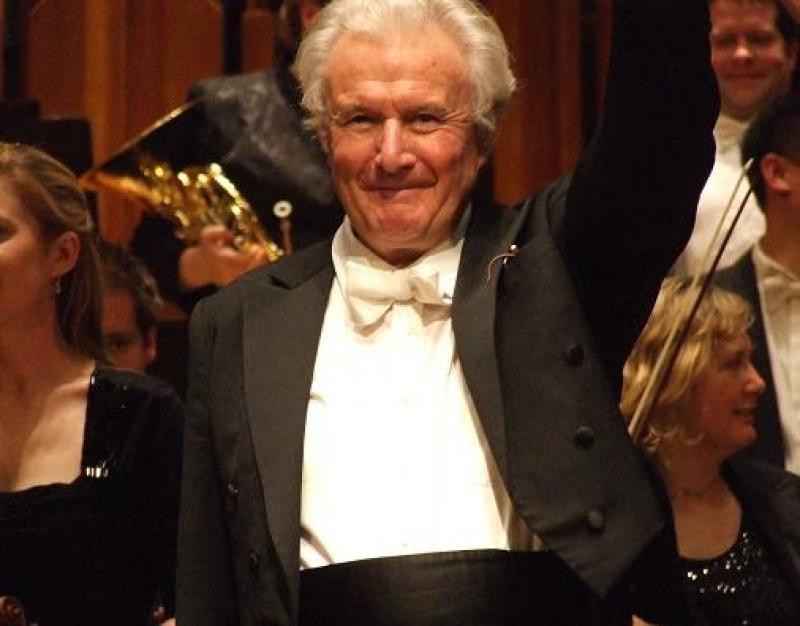

LSO, Davis, Uchida, Barbican Hall

LSO, Davis, Uchida, Barbican Hall

Chaos reigns in a performance of Nielsen's Fourth Symphony

Communists had taken over the Acropolis, Britain faced a hung parliament and in the 20 minutes it took me to get down to the Barbican by bus the US stock market had fallen more sharply than at any time since 1987. In the face of global and political madness, it was nice to have a concert awaiting that seemed to offer a sense of cosy familiarity and unfashionability and monarchical approval.

Respectability, however, was where we began. It says a lot about the orchestral climate today that a respectable performance of a work by Haydn, who exemplified respectable 18th-century society better than anyone else, should shock. But shock it did to hear the three-four first movement of Haydn's Symphony in C, No 97, performed with so much orchestral weight and focus on beauty of sound. To an extent I was reminded of Beecham, but Beecham would surely have made more of the sinking chromaticism that bedevils the apparently firm Classical ground.

The first jolts to the system occurred in Uchida's Mozart, the G major piano concerto K453. At first, her dry, staccato, pedal-less, left-hand ostinato brought a smile to my face. It was so Uchida, a reinvention from the off. But as the dryness continued, her sound starting to resemble the coy advances of a small mechanical bird, the effect was increasingly lost on me. Why couldn't she have coloured the opening with the same agogic suppleness and softness that came through in the Andante? Not sure. There is certainly a schizophrenia in this vital work but I didn't understand Uchida's two faces. The result was unsettling.

But then came the real volcanic explosion: Nielsen's Fourth Symphony, The Inextinguishable, which has an opening of unrivalled spontaneity. Encountering its first bars is like stumbling upon a revolution - or hung parliament. Davis and the LSO plunged us into it impressively, brass crashing down violently on the low strings, the orchestra forced into an aimless, exuberant, suffocated writhing (ring a bell?), throwing timpani and strings high up into the air like a volcanic ash cloud. It is an extraordinary act of ingenuity to have this unlikely duo - timpani and strings - hanging over the orchestra, precipitating its black, carpeting, fortissimos intermittently. It is not the only extraordinary act, though.

A concert that had begun with such home-spun gentility was beginning to resemble the lawless world outisde. Nielsen's symphony may be an affirmation of the inextinguishable power of musical thought - hence its subtitle - but its jittery exploration of every tonal and orchestral nook and cranny is almost viral or fractal in feel. Everything is in flux, everything new and odd.

There are what sound like tone rows from the violins, overlapping keys and modes and chromatic meanderings that move in such an increasingly tangled way as to almost swallow themselves, a folksy woodwind divertissement that is quickly made grotesque. Davis allowed these diseased themes to work themselves up into a mangled frenzy, the energy climaxing in a Varèse-like drum-off, a section that leaps into the air as if set alight, in the last movement. In the face of this unending wildness, the world outside seemed positively dull.

- Book tickets for the 9 May repeat of this London Symphony Orchestra programme with Sir Colin Davis and Dame Mitzuko Uchida

- Check out the rest of the Barbican season

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Add comment