Over 30 years after he made his debut as a solo artist, woodwind multi-instrumentalist Courtney Pine is still Britain’s most prominent and influential jazz musician. He had a crucial role in reviving interest in jazz in the 1980s and 1990s, and has been an important role model for black British musicians. His own performances have always been informed by an awareness of both his Caribbean – his parents were Jamaican – and British musical identity, and as well as jazz, he has made albums exploring reggae, ska, drum'n'bass, hip hop and more, as well as, more recently, funk and soul.

Pine talks about the wider jazz community with feeling, and his commitment to the music, as a culture and community, comes through strongly. His big band Jazz Warriors has been a nursery for much of today’s young talent. Pine has been engaged in political music-making for a long time, and was musical director of the Windrush Gala Concert in 1998.

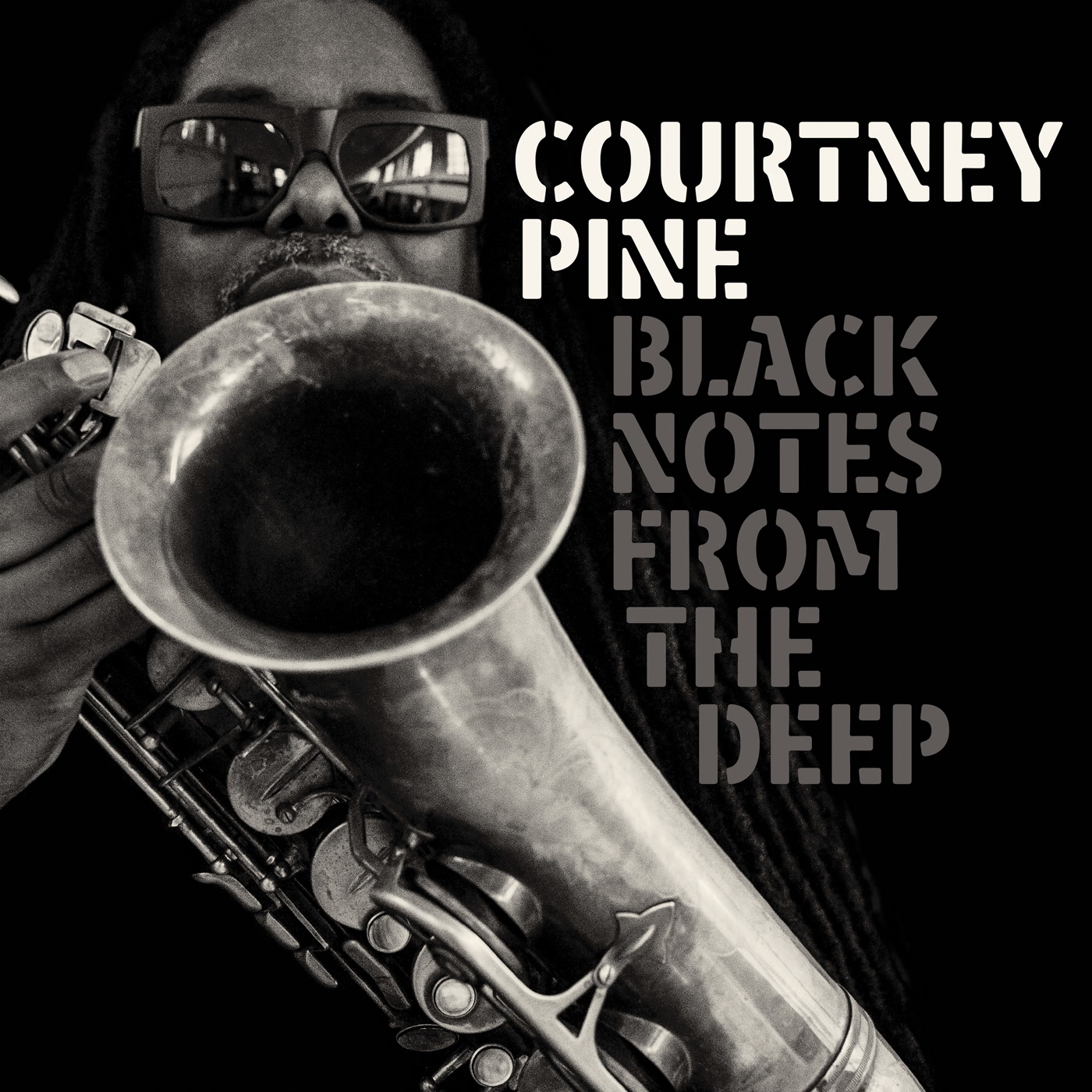

His most recent album, Black Notes from the Deep, addresses questions of identity and injustice, although in a surprisingly calm and reflective way. It contains a mellow song entitled “Rivers of Blood”, and naturally, in the light of the controversy about the deportation of the Windrush community it’s the first thing we mention.

MATTHEW WRIGHT: You have written songs about Stephen Lawrence and Nelson Mandela, among others. Do you ever despair of the political situation?

COURTNEY PINE: That album – it’s weird – I did it last November, but I could have been talking about the Windrush generation right now! I was raised in the UK in the Sixties, and jazz fans will know that jazz is about love, even in the Sixties when it was motivated by free jazz and liberation. Jazz, as love and liberation, speaks to everybody. There is rage, but how do you express rage? In the midst of battle, or in the energy of a car crash, everything slows down. That’s the energy I was trying to use on Black Notes from the Deep. You take someone like Doreen Lawrence. She was so calm, when you’d expect her to be screaming. For me, that’s the most powerful sentiment. We have the choice of art, to create in a way that is beyond the first visceral feeling.

That’s what I love about jazz. It was written such a long time ago, but it’s still relevant to what we’re doing now. Why did Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, play that way? Jazz comes from the community, it’s an expression of the community, then it breaks out. I’m talking about north west London, the Notting Hill Carnival. That’s what’s fascinating to people outside. What is it like there? What are you guys talking about? That’s what Black Notes from the Deep is really about: it’s an expression of who we are and what we’ve been through.

Some people will hear "Rivers of Blood", and think, that’s a bit too close. Other will know exactly what I’m dealing with.

When I was about 15, and I wanted to know what jazz was, I got the books. Beneath The Underdog, the Mingus autobiography, a Charlie Parker biography and Sidney Bechet’s autobiography Treat It Gentle, and I started to find out about their lives. It was unbelievable. I speak to the American saxophonist Branford Marsalis quite often, and he says, at least we’re living in this time, because it used to be a lot worse. We have to understand the pain of Coleman Hawkins, Billie Holliday and so on, and and try to represent who we are. It doesn’t mean we have to sound like them, but we have to show an understanding.

Black Notes from the Deep is a powerful title. What is the deep? Are black notes still hidden away?

Black Notes from the Deep is a powerful title. What is the deep? Are black notes still hidden away?

All my albums are about my culture. I’m not just talking about Caribbean culture, I mean British culture. That’s my culture. I’m getting better at talking about myself. That’s what jazz can do. As an instrumentalist, I always start with a long title and edit it down. It was going to be Black Notes, but Black Notes from the Deep explains why there are so many ballads, the whole process behind the record.

Looking at your back catalogue, and how it represents your culture, it’s clear that each project, going all the back to your 1990 reggae album Closer To Home, represents a different musical departure. Presumably this is your deliberate policy?

I don’t have to stay in one corner of the room. I can explore the whole room. Outside the room, on top, below, aside. Within the room there’s another dimension as well. It’s for me to research, open my mind, get to the point where I can do, say, a big band album. I recently got a call from Chi-Chi Nwanoku, founder of the all-black orchestra Chineke!, and she’s invited me to take part. So I could record an orchestral work. The limits of jazz are the limits of your imagination. All these possibilities are there. I could play in a trio for 50 years, but I want to explore all the corners and crevices of my culture. Being a jazz musician allows me to do that.

There are classical musicians, too, like Nigel Kennedy who understand that music is not just a porcelain sculpture. It’s an expression of our humanity.

Wynton Marsalis was the fuse for wanting me to be a jazz musician, when I was starting out, playing reggae gigs. Whenever I’ve met him, he’s been inspiring. Jazz musicians like flautist Hubert Laws, have stood in both camps before, but Wynton is the leading example today. He’s a great lighthouse for the music.

How did you meet Omar Lye-Fook? How did you start working together?

I used to go to summer school near the Harrow Road, Kensal Rise, Ladbroke Road. I met Omar at summer school. I was nine, he was six. He was very popular. People always wanted him in their sports teams. He could sing, play percussion. Even at that age, he had a kind of magnetism. A bit later when we were both musicians, a Japanese record company asked me to produce a tribute to Bob Marley. He came in to sing Natural Mystic, and he was great. I began following his career more closely, and discovered through the grapevine that he’s a closet jazz musician. He wants to get down in the trenches like us. He wants to explore sound. He’s not there to lip-sync, then take a bow and have some champagne, he really wants to find the next chord. I asked him to come and do a gig at Love Supreme. He liked the sound, and gradually he came round to the idea of doing jazz.

After performing with Herbie Hancock for International Jazz Day a few years ago, I had this dream that I was playing Butterfly, by Herbie Hancock, and Omar was singing it. A lot of my music is based on dreams. I sent him the tune, he was happy to do it. He brought an individuality to the project. Nobody sounds like him. He’s come out of so many influences, so many giants, and he’s created his own sound. There’s a musical openness.

I took the Butterfly lyric from a version by Norman Connors. When I asked Herbie who to credit, it turned out Herbie’s sister wrote those lyrics.

On your latest album you’ve come back to tenor saxophone after more than 10 years. What brought you back?

It’s a challenge to play woodwind instruments. I did some broadcasts with Sonny Rollins some years ago. I made the mistake of asking Sonny, if Coltrane plays all these instruments, how come you only play one. I could see the smoke coming out of his ears, but he realised he was talking to a young English boy who doesn’t understand. He said, “Courtney, it’s more of a challenge when you play one instrument.” One day, it hit me, that he does all that stuff, flute, soprano saxophone, all on a tenor saxophone. It hit me, if you can capture the same range on one instrument, that is deep! I decided to concentrate on one instrument at a time. It was soprano saxophone for House of Legends, because I wanted to inhabit the female voice of the Caribbean, where it’s the women who are the scientists, doctors or, like Claudia Jones, who founded the Notting Hill Carnival, as a brilliant way of defusing violence and tension.

This particular project is so deep for me, it had to be tenor saxophone. That’s the instrument I’ve played the longest. Coltrane is a big influence in lots of ways. People don’t always realise that he was proud of his culture, but check his titles, and who he was writing for. “Liberia”, “Song of the Underground”, “Alabama”. He was really proud of his culture. These are pieces of music that are so embracing of his humanity. That’s what music should be about.

A lot of the guys out there now on front covers, winning awards, they played in my band

Do you still practise eight hours a day?

I’m wiser. Even when you’re not with an instrument you can practise, build up the chops, work on your embouchure, and intensify your vision. Instead of just playing scales and exercises, you have to know what you’re practising for. It’s still eight hours. I have a record company, so I spend time going to jam sessions looking for talent. There are other aspects to the industry for me.

You were hailed as the saviour of British jazz in the 90s, with invigorating albums like Modern Day Jazz Stories that were rooted in jazz but infused with other genres of music. Are there echoes of your work in musicians like Shabaka Hutchings, another saxophonist rejuvenating jazz with flavours of related music?

When I got started in jazz, I used to go the clubs and ask for advice. All the elders just told me not to bother playing jazz. I was very fortunate to encounter some great South African musicians. Brian Abrahams gave me a gig. John Stevens invited me to play in his band. Harry Beckett, the Barbadian trumpeter, too, let me express my young, wild self. Since I’ve had the opportunity to be a solo artist, I’ve always welcomed youngsters into bands. A lot of the guys out there now on front covers, winning awards, they played in my band. They came and sat in my front room. We’ve shared the bread.

In jazz, you’re part of a chain. It’s not like pop. Pop is about them. This is about us. If you show the industry that you are connected to a tradition, and you’re talking about your community, you’ll be taken more seriously. So many musicians have come out of a band I formed called the Jazz Warriors. When I talked to the pop press, and said, I want to be the best saxophonist I can be, they thought I was just talking about myself. They couldn’t understand there was anything bigger than that.

The freedom you can have in the music itself is scary. Some people want to know what the dark matter is. Jazz is leading them there.

The media seems to have an ambivalent, melodramatic relationship with jazz, where it’s either dying or being saved by someone. Where do you think it’s at?

Jazz was always the rebellious music. If you talk to elders like Humphrey Lyttelton, he will tell you that. It doesn’t matter what tempo or vibe you’re playing, it’s just about breaking the social constructs. Whether it’s Jamie Cullum, Georgie Fame, or, look at Queen Latifah doing jazz now, you’ll always find people breaking through to be positive human beings. I’ve been doing it since 1987 as a solo artist. I’m still doing it. So all those naysayers who said jazz is dead, or who told me not to play jazz, they're wrong! It’s the most human form of music we have. You’d be surprised at the number of popular musicians that want a piece of jazz. Bryan Ferry, Paul Weller, the late, great David Bowie, all of them wanted to play jazz. Jazz is still alive, and functioning, and giving birth

- Courtney Pine is playing from Black Notes from the Deep at the Cheltenham Jazz Festival, with Omar Lye-Fook, on Friday May 4

Add comment