Photographer Rena Effendi: 'Images of dislocation' | reviews, news & interviews

Photographer Rena Effendi: 'Images of dislocation'

Photographer Rena Effendi: 'Images of dislocation'

Azeri photographer brings the world to us with striking, intimate immediacy

Photographer Rena Effendi’s current exhibition, "Zones of Silence", at London's Mosaic Rooms includes work from four of her recent series, and it’s hard not to see a link between them – displacement. As the exhibition notes explain: these are lives lived in areas of the world that have become invisible.

The first room shows work from Azerbaijan-born Effendi’s long study (2006-2012) of life around her native Baku, “Liquid Land”, where refugees from the now distant Nagorno-Karabakh conflict still live improvised lives in the oilfields that surround the city. It arouses strange impressions: there is paradoxical beauty in this ravaged and polluted landscape, in which everyday life continues ("Laundry hanging on the oil field. Balakhani, Baku. Azerbaijan. 2010", pictured, below right). There’s an added texture to the series – it’s not irony, since that’s the last thing I think that Effendi goes in for – in her decision to include in it images of butterflies, taken from the photographic collection of her late father, a leading Soviet entomologist, their “pure” beauty set against the very “relative” beauty of the contemporary landscapes that she depicts.

The second room begins with images from the war in Georgia in 2008, following the Russian invasion of that country; here the destruction is more obvious ("Bombed buildings on Telman street in the outskirts of Tshinvali, South Ossetia. August 16, 2008", pictured, below left). It was a time, Effendi recalls, when the quantity of international press on the ground practically exceeded the number of combatants on both sides. Effendi largely avoided direct images of conflict, preferring scenes of life continuing despite the bombardments and upheavals of war.

The second room begins with images from the war in Georgia in 2008, following the Russian invasion of that country; here the destruction is more obvious ("Bombed buildings on Telman street in the outskirts of Tshinvali, South Ossetia. August 16, 2008", pictured, below left). It was a time, Effendi recalls, when the quantity of international press on the ground practically exceeded the number of combatants on both sides. Effendi largely avoided direct images of conflict, preferring scenes of life continuing despite the bombardments and upheavals of war.

A third series catches the world of the Chernobyl “returnees”, those former residents of the area surrounding the Ukrainian nuclear reactor who have decided, against all official instructions, to return to their previous homes, despite the high levels of radiation that have mutated everything that grows in the area. The title of the series is “Chernobyl: Still Life in the Zone”, and Effendi treats some of this local harvest as a subject in itself, in pictures of strange beauty which she admits she took as much for herself, as for the assignment that had sent her there. These "returnees" are predominantly old women, who have chosen the irradiated familiarity of their former homes to whatever offers of relocation had been made. There’s a strong sense of landscape throughout the photographer’s work, or rather a sense of how human beings exist in landscapes that have themselves changed: there must be few places in the world more redolent of such emotions than Pripyat, the dormitory town for Chernobyl workers which was evacuated completely in three days back in 1986, leaving the bewildering sense of a life simply abandoned, as well as, today, of how nature has taken over ("Birch tree growing on the second floor of a GYM in the abandoned city of Prypyat. Chernobyl, Ukraine. December 2010", pictured, below right).

Effendi’s most recent series, “Spirit Lake” ("Shauncina Lovejoy, age 12 hugging her aunt Jada Longie 39 y.o. near the Crow Hill Sun Dance grounds. "I can take you in, my girl..." - Jada says to Shauncina. Spirit Lake, North Dakota. April, 2013", pictured, below left), is the final part of her London show. Dating from this year, at first sight it would appear to be a long way away from the ex-USSR world of her background. It’s a study of Native Americans in a North Dakota reservation, and the dire range of social problems that they have to cope with; they live perhaps in a state that might almost be termed “inner emigration”. North Dakota was as challenging a project as any the photographer has taken on: in a war zone, she says, you can at least sometimes see people coping, whereas here the struggle is with long term depression, heightened by alcoholism and sexual abuse in the community.

Effendi’s most recent series, “Spirit Lake” ("Shauncina Lovejoy, age 12 hugging her aunt Jada Longie 39 y.o. near the Crow Hill Sun Dance grounds. "I can take you in, my girl..." - Jada says to Shauncina. Spirit Lake, North Dakota. April, 2013", pictured, below left), is the final part of her London show. Dating from this year, at first sight it would appear to be a long way away from the ex-USSR world of her background. It’s a study of Native Americans in a North Dakota reservation, and the dire range of social problems that they have to cope with; they live perhaps in a state that might almost be termed “inner emigration”. North Dakota was as challenging a project as any the photographer has taken on: in a war zone, she says, you can at least sometimes see people coping, whereas here the struggle is with long term depression, heightened by alcoholism and sexual abuse in the community.

I spoke to Effendi this week from Cairo, where she’s been living for the last four years. There’s always a risk in analysing such links too closely, in appropriating biography into creativity, but Effendi admits that the effect of her coming-of-age experiences in Baku in the last years of perestroika was influential: there was an influx of refugees from the war, rising Azeri nationalist sentiments that would virtually destroy, with great bloodshed, the age-old Armenian community of Baku, and conflict with the Soviet troops sent in to maintain order. “Seeing all that, the internally displaced, the war refugees,” she said, “it felt like the nation was in flux. Our identities themselves were in flux.” (Despite the strong sense of dislocation evident in her London exhibtion, other series, such as one on rural life in Romania, "Built on Grass", and an outstanding black and white study of young people in contemporary Iran, "Twenty-something in Tehran", have the opposite, a strong sense of place.) Effendi’s own identity also changed when she chose to pursue a career in photography (she had studied languages at university).

It set her out on a career that has combined international locations, often in shorter trips on specific assignments (when I spoke to her Effendi was just back from one for The Sunday Times, covering the settlements in Lebanon which have become home for refugees from the conflict in Syria), with longer-term, fully “embedded” studies of communities. “Ideally the two come together,” she said. “When a subject strikes a chord, I don’t stop. The more personal offers the chance to spend more time, a different build of narrative, which can become more epic.”

It set her out on a career that has combined international locations, often in shorter trips on specific assignments (when I spoke to her Effendi was just back from one for The Sunday Times, covering the settlements in Lebanon which have become home for refugees from the conflict in Syria), with longer-term, fully “embedded” studies of communities. “Ideally the two come together,” she said. “When a subject strikes a chord, I don’t stop. The more personal offers the chance to spend more time, a different build of narrative, which can become more epic.”

Her first major such long form project, “Pipe Dreams” was published as a book in 2009 (and exhibited in part at the BUTA festival of Azerbaijani culture in London in 2010: Effendi’s current London show is part of that festival’s second edition). Its stark black and white images record life along the route of the 1,700 km-long Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, one of the region’s most important energy arteries that opened in 2005. Originally Effendi was commissioned by BP, one of the foreign companies in the venture, for an assignment to document that company’s official projects to improve community life along the route. Her BP work was limited to Azerbaijan, but she saw the potential for something more profound: “As I was driving through the villages, I saw things I wanted to photograph, but didn’t have the time. So I thought, I have to go back, and extend the idea to the entire length of the pipeline, to Ceyhan [the Turkish port where the pipeline reaches the Meditteranean].”

Two sentences from the annotation to the published book illuminate Effendi’s achievement very well: “This book portrays life as it is lived, with no commercial or public relations agenda. It ‘un-smiles’ the calendar smiles of corporate propaganda and sheds fresh journalistic light on this geopolitically important region.” Such resolutely honest perspectives in the world of the former Soviet Union have often proved unpopular with authorities who are trying to create a “national myth” of progress for international consumption. (It was a phenomenon that reached an unusual extreme in Uzbekistan in 2010, when the photographer Umida Akhmedova was put on trial – she was convicted, but then pardoned – for "slandering" her country, and that was for a National Geographic assignment!).

Two sentences from the annotation to the published book illuminate Effendi’s achievement very well: “This book portrays life as it is lived, with no commercial or public relations agenda. It ‘un-smiles’ the calendar smiles of corporate propaganda and sheds fresh journalistic light on this geopolitically important region.” Such resolutely honest perspectives in the world of the former Soviet Union have often proved unpopular with authorities who are trying to create a “national myth” of progress for international consumption. (It was a phenomenon that reached an unusual extreme in Uzbekistan in 2010, when the photographer Umida Akhmedova was put on trial – she was convicted, but then pardoned – for "slandering" her country, and that was for a National Geographic assignment!).

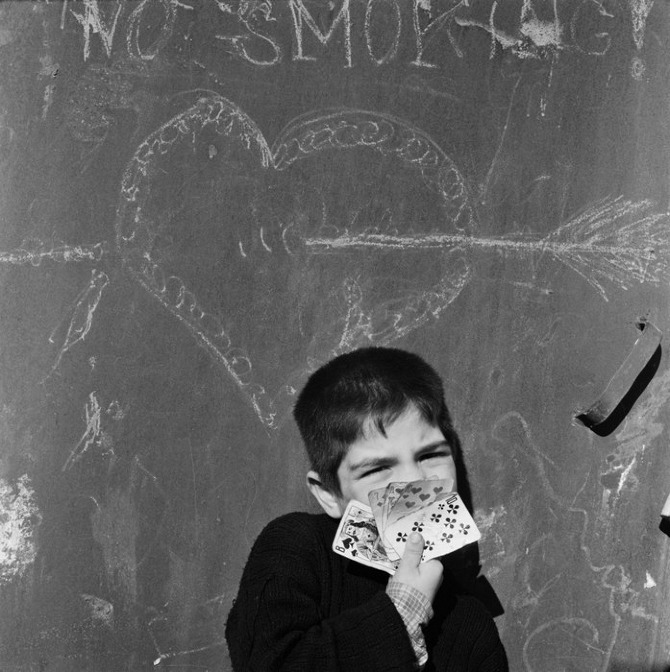

Effendi remembers Azeri reactions to Pipe Dreams very well. Some in the country’s diaspora were shocked: “They didn’t want to see such oblique pictures, showing such social disparity.” The reaction from the authorities was no less telling, with the 60 author copies sent to the photographer in Baku seized by customs, then apparently censored, before finally being burnt. “The positives were that Pipe Dreams gave a human voice to those who otherwise wouldn’t have had such a voice,” Effendi remembered, “And it showed the human consequences.” ("Boy with Cards", pictured, below right.)

It’s an empathy achieved not least by Effendi’s working methods. She prefers to shoot with a 60-year-old Rolleiflex 6x6 camera. It allows the photographer to look “down” into the lens, rather than subjects feeling that she is “behind” it, with all the attendant associations of power. “It allows you to tiptoe around the subject. And it looks so large and weird, almost like you’re carrying a musical instrument, so it’s an attraction in itself – you gets passers-by stopping to express interest in you. It’s not so aggressive, it’s like you’re working in a kneeling or praying position, far less threatening.” The drawbacks are that it’s fragile and high maintenance, and that the number of places in the world that process the distinct 12 exposures of each film decreases all the time (Cairo isn't one of them). Another advantage is that rather than shooting an unlimited quantity of digital images, each picture taken feels like it’s a conclusion of a “treasure hunt,” as she describes it. Effendi is indeed an artist who locates treasures in the most unlikely envirnonments, bringing the world to us with a very striking, intimate immediacy.

It’s an empathy achieved not least by Effendi’s working methods. She prefers to shoot with a 60-year-old Rolleiflex 6x6 camera. It allows the photographer to look “down” into the lens, rather than subjects feeling that she is “behind” it, with all the attendant associations of power. “It allows you to tiptoe around the subject. And it looks so large and weird, almost like you’re carrying a musical instrument, so it’s an attraction in itself – you gets passers-by stopping to express interest in you. It’s not so aggressive, it’s like you’re working in a kneeling or praying position, far less threatening.” The drawbacks are that it’s fragile and high maintenance, and that the number of places in the world that process the distinct 12 exposures of each film decreases all the time (Cairo isn't one of them). Another advantage is that rather than shooting an unlimited quantity of digital images, each picture taken feels like it’s a conclusion of a “treasure hunt,” as she describes it. Effendi is indeed an artist who locates treasures in the most unlikely envirnonments, bringing the world to us with a very striking, intimate immediacy.

- Rena Effendi’s "Zones of Silence" continues at London’s Mosaic Rooms until December 20. She will be present there for an exhibition talk on Thursday December 18 at 6.30 pm

- The BUTA Festival of Azerbaijani Arts continues in London until March 2015

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Album: Josh Ritter - I Believe in You, My Honeydew

The alt-country singer's latest isn't consistent but does hit highs

Album: Josh Ritter - I Believe in You, My Honeydew

The alt-country singer's latest isn't consistent but does hit highs

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Album: David Byrne - Who is the Sky?

Born to be weird

Album: David Byrne - Who is the Sky?

Born to be weird

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

Edinburgh Psych Fest 2025 review - eclectic and experimental

Underground gems and established acts in this multi-genre, multi-venue day long festival

Edinburgh Psych Fest 2025 review - eclectic and experimental

Underground gems and established acts in this multi-genre, multi-venue day long festival

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Album: Faithless - Champion Sound

Three decades into their career the perennial dance duo nail a lengthy but likeable set

Album: Faithless - Champion Sound

Three decades into their career the perennial dance duo nail a lengthy but likeable set

Add comment