Wayne McGregor wasn't anyone's idea of a ballet man when he was appointed choreographer in residence at the Royal Ballet in 2007. Before then, and since, his work has been abstract, spiky, verging on dysmorphic. His interest lay not in human stories but in the snap of synapses and the speed with which the brain can relay messages to a hyper-flexible body. Then, two years ago, perhaps sighting the end of that particular road, he made a surprising swerve into narrative with Raven Girl, which last night received its first revival at the Opera House.

Raven Girl is a fairytale which pays elaborate homage to its avian precedents in dance - specifically Swan Lake, The Firebird and Merce Cunningham's Beach Birds. This immediately sets the piece up as a potential repertory standard, but there were snags on its first run: it felt too long and it needed greater clarity. A fairy story that leaves its audience befuddled is a traitor to the genre.

Now, on its second outing, it’s certainly shorter and tighter. "Once there was a Postman who fell in love with a Raven" (don’t ask how or why) is still spelt out in Gothic type on the opening scrim, but later captions seem to have been dropped (unless I just couldn’t see them: sightlines from the sides of the auditorium are shocking). Edward Watson – hotfooting it from the Palace where he was made an MBE yesterday afternoon – still makes a sharply melancholic Postman, forever walking or cycling in circles. Delivering a letter to a far-flung address, he finds a nestling fallen from a raven's nest, takes it home, cares for it and lo, the synopsis informs us: "Some time passes and they have an egg."

The book on which the ballet is based is by Audrey Niffenegger, better known for The Time Traveller's Wife, but also a writer of short graphic novels. Her sombre drawings are incorporated into both Vicki Mortimer's picture-book set designs and Ravi Deepres's ravishing film overlays. One moment these are filling the sky with drifting pearly clouds, the next with sooty whorls of birds.

Sarah Lamb is the half-breed hatchling: human in appearance, but longing to fly. At university (naturally) she studies evolutionary biology and persuades the Doctor (a manic Thiago Soares) to perform an operation that will remove her arms and give her wings. In the earlier version, glimmering X-ray images thrillingly showed the likeness between the structure of a human arm and hand, and the intricate pin-bones of a wing. That these have been cut is a shame.

Sarah Lamb is the half-breed hatchling: human in appearance, but longing to fly. At university (naturally) she studies evolutionary biology and persuades the Doctor (a manic Thiago Soares) to perform an operation that will remove her arms and give her wings. In the earlier version, glimmering X-ray images thrillingly showed the likeness between the structure of a human arm and hand, and the intricate pin-bones of a wing. That these have been cut is a shame.

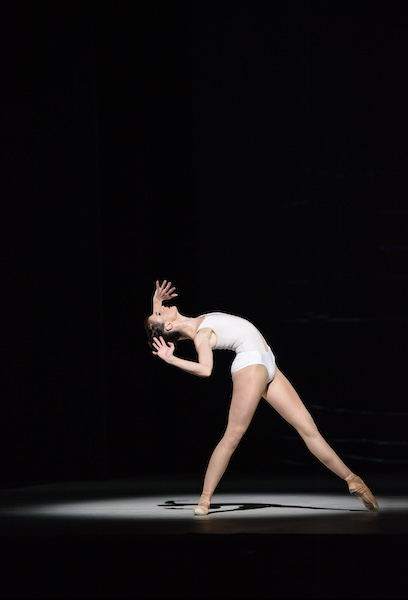

Even more of a pity is that the ending remains unclear. The moment Raven Girl gets her wings (pictured above right), prompting a heady balletic impression of swooping flight, is the point at which McGregor's tale starts to unravel. Interventions from a jealous boyfriend and horrified parents still prompt awkward questions, and Eric Underwood's Raven Prince remains ill defined. Is he a man-raven, or a raven-raven? We need to know. Yes, the handsome prince does sometimes appear out of nowhere in classic fairytales, but these days we demand credentials, or it just doesn’t wash.

The lasting impression of Raven Girl however is of a visual and aural feast, daring in its simplicity, beautifully achieved in its mix of digital and physical effects. Gabriel Yared’s score (blending live orchestra and electronics) has the surging Hermannesque sweep of his film work (The English Patient, The Lives of Others) dotted with lovely narrative details: the chug of a postal sorting office and the rhythmic flap of wings. Nevertheless, the chances of this ballet sustaining an evolutionary curve of its own are small. With its gymnastic demands it’s hard to imagine anyone but Sarah Lamb in the title role – a scene in which she executes extreme balances on a pile of chairs is a career tour de force.

The evening’s filler – sorry, choreographer Alastair Marriott, that’s how it is – was already on a hiding to nothing by coming second, but was doubly skewered by having a title no one knew how to pronounce. Connect-to-me or Connec-tome? It may seem a quibble but if you can’t say it you can’t talk about it afterwards – half the pleasure of going to the ballet. Connectome (“connec-tome”) is the scientific term for a map of the wiring in the brain, and Marriott’s half-hour ballet is purportedly an inquiry into how, in the course of our lives, each of us becomes who we are as these connections become increasingly dense and complex. It sounds like a theme of Wayne McGregor’s, but the result is not at all McGregor-like, with the predominance of smooth academic lines and group unisons, and portentous-sounding chunks of Arvo Pärt, cut from four different works for string orchestra.

The evening’s filler – sorry, choreographer Alastair Marriott, that’s how it is – was already on a hiding to nothing by coming second, but was doubly skewered by having a title no one knew how to pronounce. Connect-to-me or Connec-tome? It may seem a quibble but if you can’t say it you can’t talk about it afterwards – half the pleasure of going to the ballet. Connectome (“connec-tome”) is the scientific term for a map of the wiring in the brain, and Marriott’s half-hour ballet is purportedly an inquiry into how, in the course of our lives, each of us becomes who we are as these connections become increasingly dense and complex. It sounds like a theme of Wayne McGregor’s, but the result is not at all McGregor-like, with the predominance of smooth academic lines and group unisons, and portentous-sounding chunks of Arvo Pärt, cut from four different works for string orchestra.

As with many such abstract pieces, title and theme are really only jumping-off points for the creative team: this could have been called Connectomybankaccount for all the difference it makes. A trio of principals - Lauren Cuthbertson (pictured above left, in the part created by Natalia Osipova, who isn't performing in this run), Steven McRae and, yet again, Ed Watson (give the boy a night off!) - are set in counterpoint against a corps of four more boys, and one can occasionally divine, between all the busy leaping and turning, the vague outlines of emotional interaction. There are some extraordinary moments – a terrific solo for McRae ends in his disappearing into a scrum of boys like a folded leaflet posted through a letterbox – but these moments are rare.

More memorable by far is the combined effect of Es Devlin’s stage design and Luke Halls’video. What begins as a glittering monochrome curtain dissolves into a forest of silver pillars, which in turn morphs into a jumble of rods, a tangle of wires, a dense nest, gaining colour as it goes. Whether this is enough in itself to alter any audience member’s personal connectome is a moot point.

- Raven Girl/Connectome are on in repertory at the Royal Opera House until 24 October

Add comment