Storyville: Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Storyville: Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones, BBC Four

Storyville: Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones, BBC Four

The tale of a maverick Welsh journalist, who saw Soviet and Nazi realities before his 1935 murder

The Storyville documentary strand must rank as one of the special glories of British television. As its opening titles unfold in different languages, we can only celebrate programmes that still give time to international stories, told in their own time, and allowing an eclectic, sometimes oblique view on their subjects. Hitler, Stalin and Mr Jones, a film by George Carey (pictured below), serves as a rallying cry to endorse exactly that.

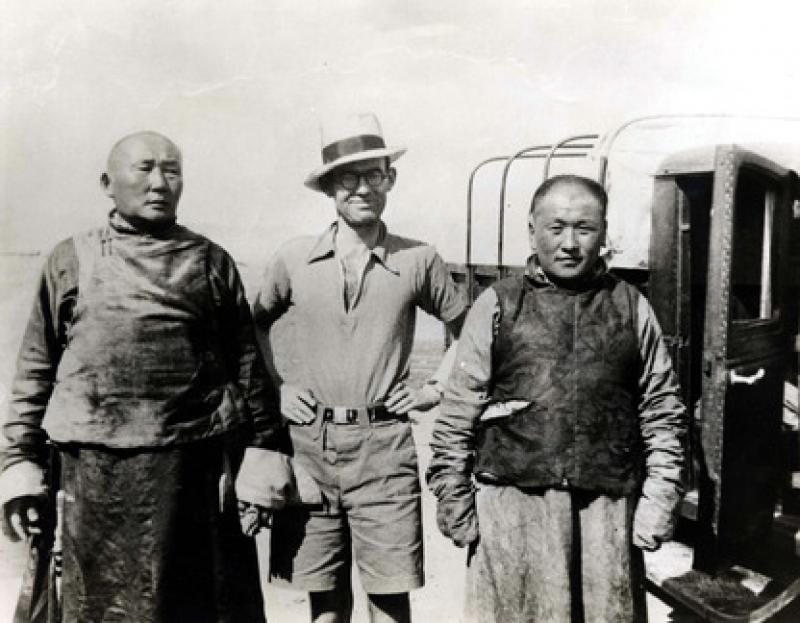

The “Mr Jones” of the title was a Welsh journalist, Gareth Jones, whose career in the 1930s and before took him to both Hitlerite Germany and Soviet Russia, to observe, at very close quarters, the realities of those countries. Supported by the patronage of another eminent Welshman, David Lloyd George, his access to the inner circles of both countries was privileged: he flew once on Hitler’s private plane, describing that leader later as looking like a “middle-class grocer”. Goebbels, in turn, received the resemblence moniker of a South Wales miner.

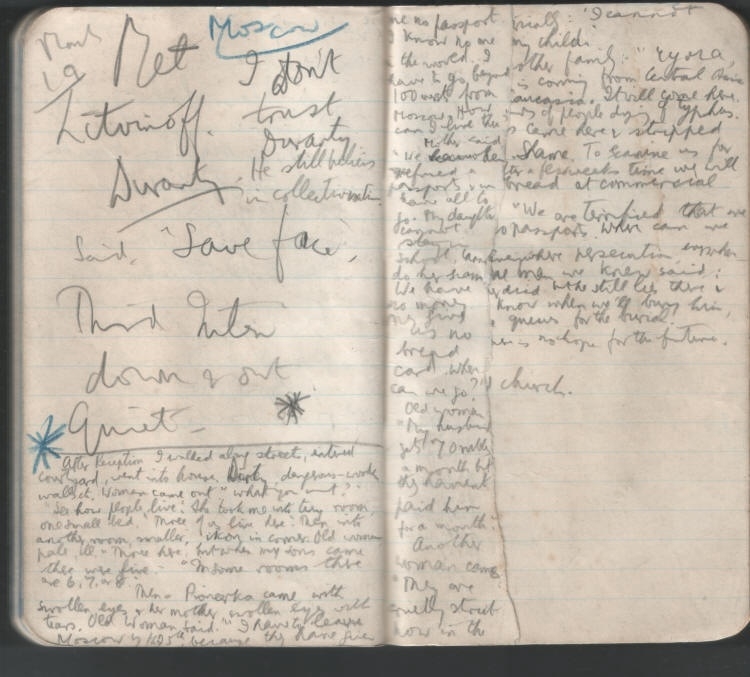

Reporting that crisis by the Western press accredited in Russia – with all its difficulties and limitations, then as now - was sporadic indeed: the New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty (notes from the diary of Jones on meeting Duranty, below left - "I don't trust Duranty - he still believes in collectivizaiton" fell for the official line, and his Pulitzer prize was very nearly withdrawn recently for those mistakes. His disputes with Jones leave little to Duranty's credit. Malcolm Muggeridge, writing for the Manchester Guardian, got more of it right, not least on the back of his correspondence and meetings with Jones, who was writing for The Times, though Muggeridge's support for the Welshman when needed, was not exactly forthcoming.

If Carey’s film leaves one issue open, it’s the personal side of Jones’s life (though we see plentiful, and moving interviews from his surviving relatives, as well as full and impressive documents, including his notebooks and diaries. Other Joneses, relatives not by blood, but through archives, are also in evidence). The director’s narration is distinctly low-key, unlike some more evocative approaches by some of his BBC Four colleagues. If we follow the espionage line, perhaps Jones was indeed something of a “cipher”, whose identity finally escapes definition.

Carey was the founding editor of Newsnight, and a balance of news and documentary has been crucial in his career – including the gap between the “big” projects, like Jonathan Dimbleby’s five-parter on his journey through Russia, that Carey produced, and smaller films. As a director, he’s made three recent documentary films that caught Russian society today from “below the surface”. It’s a hand-held, minimal-crew style, that brings the rewards of authenticity, in the best Storyville tradition. Mr. Jones trumps even those earlier works, and surely has BAFTA written all over it.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Bookish, U&Alibi review - sleuthing and skulduggery in a bomb-battered London

Mark Gatiss's crime drama mixes period atmosphere with crafty clues

Bookish, U&Alibi review - sleuthing and skulduggery in a bomb-battered London

Mark Gatiss's crime drama mixes period atmosphere with crafty clues

Too Much, Netflix - a romcom that's oversexed, and over here

Lena Dunham's new series presents an England it's often hard to recognise

Too Much, Netflix - a romcom that's oversexed, and over here

Lena Dunham's new series presents an England it's often hard to recognise

Comments

Jones reported on the 1932