theartsdesk Q&A: Director Sir Jonathan Miller | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Sir Jonathan Miller

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Sir Jonathan Miller

The legendary director lets rip

Doctor, writer, sculptor, curator, comedian, presenter and director, Sir Jonathan Miller (1934-2019) was one of the mighty cultural and intellectual omnivores of our age.

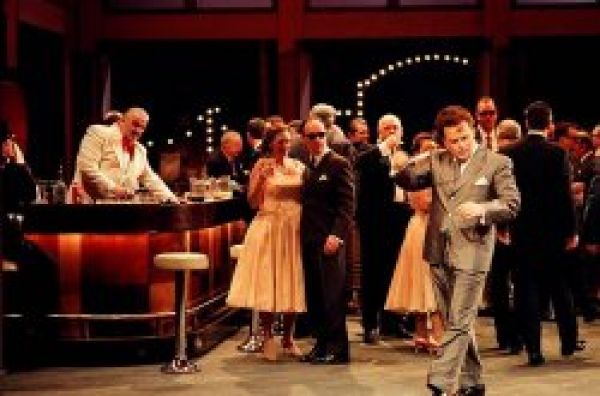

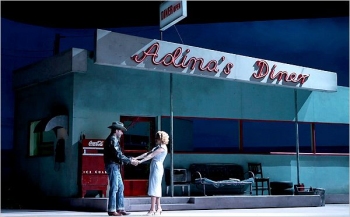

In 2012, as he returned to the ENO with a new production of Donizetti's The Elixir of Love set in a service station and diner in the American Midwest, he talked to theartsdesk of the stress of getting American accents past the ENO musical staff, the genius of Jack Benny, Seinfeld and Tolstoy, the vulgarity of Wagner, the horrors of Zeffirelli, the "problematics" of the neo-conceptualists, the pesky "infant dinosaurs" Alagna and Gheorghiu and his love of reality TV.

IGOR TORONYI-LALIC: I enjoyed your Rigoletto here [revived at the ENO last year] and your current revival of Così fan tutte at the Royal Opera House. What do you think of revivals of your work? You have such a hands on detailed approach to opera directing is it not scary leaving it up to others to recreate that?

SIR JONATHAN MILLER: I have been very fortunate in my relationships here and indeed at the Royal Opera House in the two opera productions I've done there in that I have always had assistants who are minutely acquainted with what I was trying to do. They are not trying to, as it were, pull a fast one. Generally, they do it very well indeed, with great fidelity and conscientiousness. Nevertheless, there is something that you add when you come back yourself. Partly because you have had new ideas - not fundamental changes but new ideas - but also because you have to make allowances for the fact that the cast has changed. You can't impose on people with whom you created jointly that particular pattern of behaviour to all identify with everything that their predecessors did.

SIR JONATHAN MILLER: I have been very fortunate in my relationships here and indeed at the Royal Opera House in the two opera productions I've done there in that I have always had assistants who are minutely acquainted with what I was trying to do. They are not trying to, as it were, pull a fast one. Generally, they do it very well indeed, with great fidelity and conscientiousness. Nevertheless, there is something that you add when you come back yourself. Partly because you have had new ideas - not fundamental changes but new ideas - but also because you have to make allowances for the fact that the cast has changed. You can't impose on people with whom you created jointly that particular pattern of behaviour to all identify with everything that their predecessors did.

I imagine you enjoyed doing the technological updatings in the recent Covent Garden Così?

Well, yes, as time has gone on mobile phones have come in and I just thought, well, hang on, these girls, who in the traditional 18th century are extolling the appearance of their lovers on these cameo brooches, they'd be summoning them up on their mobiles in 2010.

You have a great mantra for your directorial style that I often nick and use for other things: "Anything that is considerable can be found in the negligible". Where do you find these negligible details? Do you try to hunt down them down or is it just acquired through simple observation?

You are doing it yourself now. Here you are talking, "Where do you find..." [he mimics my hand gestures]. I could understand everything you were saying if I were listening to you on the telephone. It does not enhance the intelligibility of what you are trying to say but nevertheless I notice that when you are talking you are moving your hands. And I am absolutely preoccupied with the relationship of gestures to the spoken language. So all these details which I talk about are all there right in your face. You haven't got to dig for them. Nor are they these brainless concepts which now have become so fashionable. It's just natural history. It's the sort of thing that Darwin based his theories on. He spent hours and hours and days and weeks and years watching the negligible details of how different the individual members of a litter were from which he said that these variations might be the basic material out of which things can evolve. It is just a question of never underestimating the negligible. It may turn out to be that that's where the prize is to be found.

It's why people were so shocked perhaps by your style at the beginning of your directorial career. Your approach seemed too economical for a form that is so often about exaggeration and over-acting.

Well, theatre, and opera in particular, has been characterised by sentimental vulgarity, by exorbitance and the belief that, in order for it to be entertaining, in order for it to be diverting, for the audience to be taken out of itself, it must do something that is in fact different from what they see in real life. I think that the most exciting thing is to have your attentions drawn to something that you overlooked in real life. Most of the things which make people laugh, the really comic things, are never bits of comic business; they are bits of observed reality which you had previously not noticed and the comedian or the comic artist has drawn your attention to what you overlooked and [he claps his hands together dramatically] you start laughing because you think, "Oh yes, of course!"

Well, theatre, and opera in particular, has been characterised by sentimental vulgarity, by exorbitance and the belief that, in order for it to be entertaining, in order for it to be diverting, for the audience to be taken out of itself, it must do something that is in fact different from what they see in real life. I think that the most exciting thing is to have your attentions drawn to something that you overlooked in real life. Most of the things which make people laugh, the really comic things, are never bits of comic business; they are bits of observed reality which you had previously not noticed and the comedian or the comic artist has drawn your attention to what you overlooked and [he claps his hands together dramatically] you start laughing because you think, "Oh yes, of course!"

There are often little routines which are comic but they draw your attention to little details about language. A wonderful one for example is Jack Benny's [left] famous radio thing with the feet in the darkness and the [threatening, low] voice saying, "Your money or your life!" "I said, your money or your life!" [A weaselly reply:] "I know, I'm thinking." [Laughter.]

Now, why do we laugh. We laugh of course because it draws attention to the idea that this is something which requires thought, the idea that it requires thought to give up your money or to give up your life. Therefore almost all the great things that make people laugh is drawing attention to aspects of thinking and aspects of experience which have previously not been noticed.

You often draw on other art forms when you direct. In last year's La Bohème [at the ENO] it was film, most brilliantly. In the classic ENO production of The Barber of Seville [left] I can't help but feel - and this might say something about my vulgar education - it has something of the TV sitcom about it?

You often draw on other art forms when you direct. In last year's La Bohème [at the ENO] it was film, most brilliantly. In the classic ENO production of The Barber of Seville [left] I can't help but feel - and this might say something about my vulgar education - it has something of the TV sitcom about it?

Oh yes. Well, the best sitcoms - the really good ones - don't involved lots of comic business; they just involve reality. Seinfeld is filled with pieces of accurately observed New York Jewish behaviour.

I also wonder how you feel towards reality TV? You may be horrified by this but, in many ways, it seems to me that you are undertaking a similar sort of investigation: the quotidian habits of people.

It's very interesting you should say that. It has become a sort of standard announcement of contempt that things like Big Brother are hateful. There is a sense in which of course they are absolutely hateful, particularly when they call them celebrities when you can't think of what they're being celebrated for. But actually if you put people into an enclosure for a long period of time the negligible, silly things that people do when they are actually forced to sleep in the same room as each other, to share the same lavatory and to know that in fact they are in some sort of competition with one another for keeping their possession and winning a prize, if you watch it and can endure the senseless boredom of the actual event. In the middle of this senseless boredom is the absolutely fascinating detail of people facing boredom.

Moving onto to your new production of Donizetti's The Elixir of Love (pictured above). It's already had a run in New York, right?

Moving onto to your new production of Donizetti's The Elixir of Love (pictured above). It's already had a run in New York, right?

We did it first in Stockholm, four or five years ago for the Royal Opera there. Then we took it to New York. First of all again I have returned to things and find that I can improve. I like returning to things again and again. Here we have to sing it in English. They sang it in Italian in both places, in Stockholm and New York, with surtitles. Well, here we do it English because that's what we do at the ENO. It immediately occurred to me that here was an advantage because I could actually have them speak in the language of the setting, ie, in the south-west of America. And against great opposition from the musical staff, I managed to persuade them.

How?

Because it was a fait accompli. Actually, what is so interesting is that 25 years ago English actors could not do American accents. I remember watching Lawrence Olivier playing in Long Day's Journey into Night and it was absolutely absurd. Now both Americans can do English and vice versa. Look at Renee Zellweger in Bridget Jones's Diary: a perfect English accent. We have all seen so many movies, so much television, now that practically any singer can put on a fairly convincing American accent. We were also very lucky in getting someone who did a brilliant translation. It's so vernacular.

Who did it?

Kelley Rourke, who I met first of all earlier this year when I was doing a Traviata in upstate New York at Glimmerglass Opera. She did the surtitles there. She's a very accomplished literary woman. She dashed off - within a month - one of the most vernacular and brilliantly witty scripts I've ever worked with. And all the singers reacted; they start playing it [he puts on an midwest American accent] "like that".

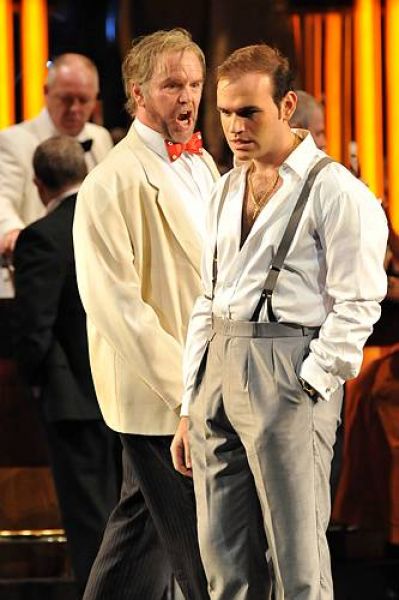

It was one of the things that I missed in Rigoletto (pictured right), American accents.

It was one of the things that I missed in Rigoletto (pictured right), American accents.

Let me tell you! When I first did it 30 years ago, there was no question about doing it in an American accent because it was generally assumed that there is a standard English in which English opera is sung. I think it's called received English. Well, received by whom!? It's just a sort of chorister's English, a sort of High Wycombe English and it bears no relationship to what's being spoken. I gradually managed this time in the revival [of Rigoletto] to get at least half of the junior cast to do them in American accents. But I couldn't get the man who played Rigoletto [on left in picture] to do it. He just refused because he was fossilised.

Wasn't he American?

No, he was English.

One of them was American, no?

Oh, the American (Michael Fabiano, pictured above right on the right) was wonderful. He played the Duc and he came from a mafia family.

What has changed on the musical management side since then? Because you say that the music department were still reluctant but were persuaded.

What happened was that they were faced with a fait accompli because I wasn't willing to back down. It's either in or I'm not. And they came and they suddenly realised that American English is not a degenerate form of received English, it's simply another form of English. They kept on saying at the beginning, oh, well, the 'rs' will violate the resonance and the pronunciation. I said it won't at all!

I wonder how your radical approach to opera was greeted in Italy where you have worked a lot and where this economical approach is still very foreign. For example, you did La Fanciulla del West at La Scala in 1991. How was that?

It was very well received.

Were the singers responsive?

Così is an abstract thesis on the nature of identity, not fidelity

Yes, they were responsive. Florence was where I had the most difficulty but the production overcome it. It's rather interesting you should raise this. Something like 19 years ago, Zubin Mehta asked me to come to the Florence to the Maggio to do my first foreign production. And I did Tosca. Now I don't believe that sort of Napoleonic Italy about which Puccini knew nothing at all. People always complain about my updating and never realise the enormity of the backdating that most people working in the 19th century went in for. Anyway, I had seen a film of Rossellini's Rome, Open City about the murder of the Italian Partisans by the Germans. I made the Germans the Italian Fascists, and the press heard about it before we had even done it and many in the audiences made huge protests and threatened to picket the place. So I stood on the wings on the first night thinking, oh dear, here come the boos. And the curtain came down and there was a three-second silence and suddenly, as the curtain went up on the curtain call, half the audience had come to the front and were applauding and sobbing. People came up to me at the stage door and pushed pieces of paper into my pocket with the names of brothers and sons that had been killed by the Fascists and said thank you for remembering our dead. And [dramatically claps his hands together] it worked.

So there's two sides to the famous loggionisti [the notoriously difficult-to-please Italian season ticket holders]. They can behave repellently but they also know truth when they see it.

If it's honest and generally revealing on the whole you can overcome those things. I find myself between two millstones of idiocy. One is the millstone of a sort of picturesque literalism in which people go there in order to see last year's vacation on stage: [in American accent] "Oh my God! We were there last year and it looks exactly like that." And if a horse draws a carriage across the stage they go ape-shit with delight. A horse that goes unapplauded across Central Park is treated as an orthopaedic achievement on the stage.

A route exemplified by Zeffirelli, right?

Zeffirelli. Absolutely. There's that millstone of idiocy. The other one is the new arrival of concept regime, conceptual productions.

Exemplified by Robert Wilson perhaps?

Oh, Robert Wilson is one of them. But there's a whole cluster of them. It's spread like HIV into England mostly by people who have never been acquainted with a concept in their life. The only thing I want to see is something which is as conceptual as accuracy. That's the only thing that interests me. Updating I will only do with certain works which have been conspicuously and vulgarly backdated. I wouldn't change the period of La Traviata because it is written in the same period as the composer. I wouldn't dream of changing Figaro or Don Giovanni. Then you might say, why did you do it to Così fan tutte. Well, Così doesn't take place anywhere; there are no social relationships of servants and aristocrats as there are in the other operas. Così is an abstract thesis on the nature of identity, not fidelity, but identity. And although I have done four productions of Così which I have conscientiously set in the 18th century I suddenly decided it would be quite interesting if we put it in last Thursday afternoon and see if the basic structure is transferable to modern life.

I looked into the archives to find a review of your very first opera production of Alexander Goehr's Arden Must Die to see if your directorial position has changed over the years. As you might expect, Alan Blyth in Opera magazine damned the production. But, intriguingly, he damned it for being overly formal and Brechtian. I can't imagine you ever being Brechtian.

I wasn't a Brechtian. I just wanted to have it stylised. It's written by a modern composer. It can't take place in the historic world in which it nominally occurs. You have to do something with it. It wasn't conceptual; it was simply smart.

You haven't shifted your stance then?

You haven't shifted your stance then?

No, I have a standard way of explaining it. If it's written in a distant kitschy past, what I call a Madame Tussaud's history, that is a behaviour up with which I will not put. It's vulgar. It's Zeffirelli-esque and I won't do it. And most of the operas that are set in that period I wouldn't deal with anyway. I won't do Trovatore. I think most of Verdi's operas are musically miraculous but absolute dramatic rubbish. There are about 25 or 30 operas that I can bear to do and I think I have done most of them.

I've always enjoyed Verdi's Stiffelio.

Yes, well, that's set in its own period.

It's got such a good tension between husband and wife, don't you think?

They expect her to come on a sort of Mardi Gras float

Yes, that is one of the few remaining operas that I have any interest in... Imagine doing Aida. The audience always say, "I love the pyramids!" And you can imagine the management: "Jonathan, there's got to be pyramids." The same vulgarity overtakes for example The Magic Flute (Miller's production for Zurich Opera pictured above left). What people forget about The Magic Flute is that it's written about 16 months after the fall of the Bastille and about 18 months before the onset of the Terror. In that period when Wordsworth said, "Bliss was it in that Dawn" - and listen "Dawn" - "to be alive/ And to be young was very Heaven." That moment when the restraints, the doctrinal, dogmatic restraints of the traditional past had been loosened under the, again, note, En-lightenment. Why is she called the Queen of the Night? Why does Sarastro say at the end,"The rays of the sun have driven away the darkness of night". They always ask you how are you going to bring on the Queen of the Night. and I always say, "Well, unless she's got any ankle problems she's going to walk!" "You can't do that!" they say, "She's the Queen of the Night!" They expect her to come on a sort of Mardi Gras float. I say she's the Empress Maria Theresa, she epitomises Catholic dogma which the Enlightenment is beginning to loosen.

You seem to be trying to sweep away the many layers of dust that opera has acquired. There's a love-hate struggle there with...

The critics.

The critics, OK, but also the operatic establishment.

Yes. But I'm also fighting against these insane neo-conceptualists. I remember talking to a Dramaturg in Frankfurt when I was doing The Flying Dutchman. I knew exactly how to do it. It's very simple. It wasn't a concept. I was basing it all on the appearance of those wonderful pictures by Casper David Friedrich, you know, those wonderful oceanic scenes with people staring out of windows and harbours and things. So, he said, "What is your concept!" I said, "I haven't got a concept! I know where it will be set and I know its relationship to the supernatural is the Romanticism of the mid 19th century." He glimmered at me through his bottled spectacles: "Without concept Dr Miller. You will have great problematics with your praxis." [Laughter.]

They're very annoying, I agree. However, they sometimes do good things in spite of themselves.

I don't think so. I think it's all rubbish. All that there is is a modest intelligence. When you are trained as a doctor you are trained to look for negligible details that give the game away. You notice someone coming in and they're doing that all the time [he rubs his fingers together] and you know they're on the edge of Parkinson's. But if you don't keep your eyes open and notice this thing called pill-rolling you'll miss it. And that's all that happens all the time. Any opera that's worth doing - and many are not because they're such worthless, silly, vulgar stories - the way Janacek's operas are and the way that 90 per cent of Mozart's are - and some of Verdi's and some of Puccini's - you can reacquaint people with what the underlying truth of the work is by drawing their attention to the underlying truth of their own lives.

It sounds like what you're aiming for is a certain rightness. That may sound glib but what I mean is that it's almost a scientific pursuit. You are trying to illuminate the quiddity of each work.

Yes, what's in front you. What in fact are the structures in front of you which you have previously overlooked. The response that I would most hope for, which I rarely get from critics, is the response that Thomas Henry Huxley gave the night after he spent the whole day and night reading The Origin of the Species. He closed the book and said, "How stupid not to have thought of that." The most interesting things that occur which can be said about human behaviour are almost always by drawing attention to something which the less talented overlook. One of the things I always say to singers is that one of the great moments in Anna Karenina - an absolutely brilliant insight by Tolstoy - when Karenin goes in front of the lawyer, who sits on the other side of the table scribbling the details obviously bored with this client, for whom it is in fact the most dramatic and terrible thing in his life, Karenin notices that the lawyer is looking... [Miller's eyes follow the trail of an imaginary moth and his hands flatten it] because a moth has gone by.

The point is, I guess, that Tolstoy is actually a miniaturist.

Yes, well, that's all there is. You do something on the scale of War and Peace in the gigantic panorama and it's the negligible details of these people who are, all of them, like all of us, en route to the grave.

Y ou said something brilliant on the Andrew Marr show just before the start of your ENO Bohème (pictured right). Marr had asked you a sloppy question, something like "What is your aim in opera?" And you said that your aim is - and I paraphrase - to make it less of an insufferably pretentious self-important art form. That love-hate relationship often seems to tip over into real hatred. Do you ever think, "I'm through with opera"?

ou said something brilliant on the Andrew Marr show just before the start of your ENO Bohème (pictured right). Marr had asked you a sloppy question, something like "What is your aim in opera?" And you said that your aim is - and I paraphrase - to make it less of an insufferably pretentious self-important art form. That love-hate relationship often seems to tip over into real hatred. Do you ever think, "I'm through with opera"?

Yes, I do. I very often I think that. I often think I'm through with the theatre and people have got very tired of hearing me say it. I have had this equivocal view about why I ever gave up what I was destined to do because I was interested in nature. But I fell off the edge of that profession into this. I think what I did was that I went into this profession carrying with me all the intellectual and technological luggage which I had acquired as a result of being a scientist for 10 years.

The music is extraordinary but they're just simply Harry Potter set to music

What draws you back to opera then when you have had these moment of crisis. The music?

No. The fun. And also the possibility of restoring these operas to an unquestionable accuracy and a finesse of observation which is what make Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina interesting.

Why have you not done any Wagner?

I have done The Flying Dutchman.

Why not the others?

The music is extraordinary but they're just simply Harry Potter set to music. [Laughter.]

One Italian opera writer once said that there is more scope for a director to intervene in a German opera because they're mainly about myth and and legends whereas Italian operas are about the conflicts between and within individuals.

Well, that's the only thing I'm interested in. I'm not interested in myths, [except insofar as I have a] long association and familiarity with Anglo-American anthropology. Myths are in fact part of the history of human thought. It is something with which modern people who can take a subway to Archway need not concern themselves with. Earthquakes which still intervene and arouse almost supernatural dreads are accompanied by huge flying aircraft bringing in medical supplies which did not happen in the Old Testament nor did they happen in the Norse myths. Myths are in fact the ways in which the ill-equipped handle the unmanageable and the unintelligible.

You haven't done much modern opera. You did the Goehr early on and Franz Shreker's Die Geseichneten at Zurich Opera.

Oh I hated that. It was so silly. I did it because it was the first thing that they asked me to do.

Have any others interested you?

I have never had any that have really interested me, no. They have almost all been works from the past of one sort or another. Partly, because I am very fascinated by the relationship of works which have outlasted their authors' wildest dreams for posterity. I wrote a whole book on this, Subsequent Performances. I have always been interested in works of art which continue to engage the interest of the audience who are so different in their understanding from the people for whom it was written. On the whole I am not acquainted with modern operas.

Is that because you don't like modern music?

Is that because you don't like modern music?

No, I like modern music very much indeed. But I haven't come across a story which interests me very much. But you must understand that I have a curious misanthropic tendency. I don't ever got to the theatre or the opera. I have other things to do. I like doing it because I'm an Indianapolis race-track mechanic. I like being in the pit changing the tyres, changing the carburettor.

So do you like dealing with singers? They can be notoriously difficult.

What's so interesting is that if you get young singers, they're susceptible to interesting ideas. If you're dealing with the Jurassic Park singers. [In a Spanish accent] "No, Jonathan, I don't think that Alfredo would do that." And you say, "You don't understand?! Alfredo doesn't exist!"

Are we talking here about Placido Domingo?

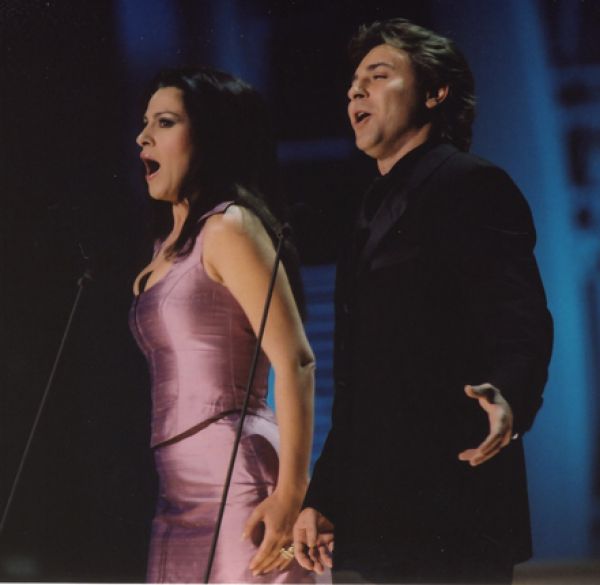

Well....[mumbles a sheepish half-yes]. But the youngsters are very very good indeed. Every now and again you get these infant dinosaurs like Alagna and his wife [Gheorghiu, both left] who have risen too quickly from the depths and have got nitrogen bubbles in their soul.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Comments

...

...