The Story of Film: An Odyssey, More 4 | reviews, news & interviews

The Story of Film: An Odyssey, More 4

The Story of Film: An Odyssey, More 4

Mark Cousins' magisterial odyssey gives a new focus to cinema history

After the first two parts of Mark Cousins’s magisterial The Story of Film: An Odyssey, I’m still in two minds as to whether it’s fair to call the presenter a generalist. He has already managed to piece together details from the cinema cultures of almost every film-making nation on earth with the authority of a specialist – and that’s before his narrative has formally progressed beyond the arrival of the talkies, let alone colour.

Cousins, who hails from Northern Ireland, has been a familiar figure in Britain’s film world, as presenter of BBC series like Moviedrome and Scene by Scene, as sometime director of the Edinburgh Film Festival, and as an acclaimed documentary maker in his own right. He nails his critical colours firmly to the mast from the very beginning of this series – it’s not going to be an examination of a multimillion dollar global entertainment industry, but of an art form distinguished by passion and innovation. This ideological opposition is presumably going to become more intense as the series develops, but it’s already there by the later half of episode two, as Cousins extols the work of the more “difficult” - in that they didn’t fit into the system - directors of early Hollywood such as the documentarist Robert Flaherty, and masters like DW Griffith, Eric von Stroheim and King Vidor.

These early decades are inevitably coloured by the sheer speed of technical innovation

At this point, at least, the opposition is softened by the fact that “popular” Hollywood – with its “dictatorship” over the artistic, in Henry Miller’s words, and “standardisation of control” that came with technology – is represented by the comic geniuses of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Hollywood will likely remain the nexus for future comparison, and in a film that scores very highly on its visuals, the image that Cousins comes up with for it is a bauble hanging in the nearby hills. It symbolises the initial attraction of the new centre of cinema, developed in the garden of California, financed by East Coast money, and created largely by immigrants, often Jewish, from Eastern Europe. But it’s not long before we see that bauble crash into smithereens.

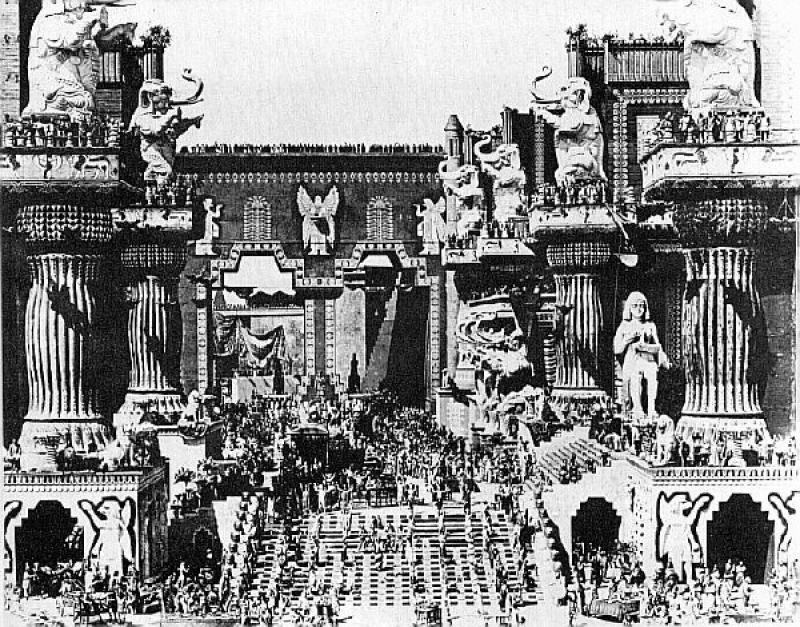

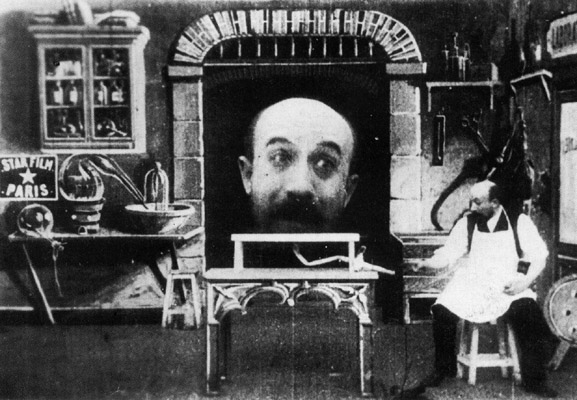

These early decades are inevitably coloured by the sheer speed of technical innovation. We started, of course, with the Lumière brothers in Lyon and Thomas Edison in New Jersey, moving through the appearance of filmic elements that are so familiar to us today that it’s good to be reminded of their radical innovation in their times – from the cutting technique, and with it the rise of editing, the appearance of the close-up, and the impact of France’s Georges Méliès, credited as the first director of special effects (pictured above). Other changes were more organic, such as the appearance of the full-length feature (The Story of the Kelly Gang from 1906, made in Australia some years before Hollywood would move beyond shorts), as well as the beginning of the star system (though who remembers the name of Florence Lawrence, the “Biopic girl”, today?).

These early decades are inevitably coloured by the sheer speed of technical innovation. We started, of course, with the Lumière brothers in Lyon and Thomas Edison in New Jersey, moving through the appearance of filmic elements that are so familiar to us today that it’s good to be reminded of their radical innovation in their times – from the cutting technique, and with it the rise of editing, the appearance of the close-up, and the impact of France’s Georges Méliès, credited as the first director of special effects (pictured above). Other changes were more organic, such as the appearance of the full-length feature (The Story of the Kelly Gang from 1906, made in Australia some years before Hollywood would move beyond shorts), as well as the beginning of the star system (though who remembers the name of Florence Lawrence, the “Biopic girl”, today?).

The Story of Film is clearly going to work in different ways for different viewers, depending on their knowledge of the subject. Even for those who think they know it well, Cousins offers some revelations – who would have thought that of the successful Hollywood scriptwriters of the early days, more than half were women, among them Frances Marion, the highest-paid member of her profession from 1915 to 1935 (and she was writing in every genre, including the boxing movie, not just romantic or domestic dramas)?

The other thing he does is to place cinema in a firmly international context – something that might need no restating, were it not for the fact that it’s just this element that has been disappearing from the general context of cinema knowledge and appreciation in recent years (compare the number of repertory cinemas in London showing international films and retrospectives now with 20 years ago, even if you argue that DVD subscription libraries have partly taken their place).

Cousins makes such links effortlessly across generations and countries – episode one showed him as a strong fan of the classic Scandinavian directors of the 1920s. Perhaps there’s nothing that surprising in linking Denmark’s pioneer Carl Dreyer (pictured left) with his modern-day colleague Lars von Trier, but then there’s Jean-Luc Godard in the equation, too. Or that Chaplin’s “little man” comic persona would be emulated not only in France and Italy, but also by Raj Kapoor in India?

Cousins makes such links effortlessly across generations and countries – episode one showed him as a strong fan of the classic Scandinavian directors of the 1920s. Perhaps there’s nothing that surprising in linking Denmark’s pioneer Carl Dreyer (pictured left) with his modern-day colleague Lars von Trier, but then there’s Jean-Luc Godard in the equation, too. Or that Chaplin’s “little man” comic persona would be emulated not only in France and Italy, but also by Raj Kapoor in India?

Clearly there are many further excursions to the capitals of world cinema of the last century to come, a filming process that can’t have been too logistically onerous given that Cousins is his own cinematographer, as well as director and writer. And he creates a remarkable visual texture to the scenes he’s shooting that is distinctly filmic in itself – cityscapes often look overcast and sparsely populated, dwelling on buildings placed symmetrically in the centre of the screen. Talking-head interviews come only sparingly, with perhaps four or five to be found in the first two episodes.

Most notably, Cousins (pictured right) himself is something of an “anti-presenter” – we haven’t seen him once on screen yet, and it’s a fair bet that we won’t later in the series, either. Instead we have his voice, softly spoken with an Irish lilt to it, achieving a real poetic quality when combined with the images. (As far a contrast as you could hope for from certain other arts and history presenters who shall remain nameless, but are to be frequently seen on BBC Four labouring to convey their visceral enthusiasm for their topics through a succession of upbeat “wow” moments and accompanying intonations that leave you hoping they aren’t doing themselves any lasting medical damage in the process.)

Most notably, Cousins (pictured right) himself is something of an “anti-presenter” – we haven’t seen him once on screen yet, and it’s a fair bet that we won’t later in the series, either. Instead we have his voice, softly spoken with an Irish lilt to it, achieving a real poetic quality when combined with the images. (As far a contrast as you could hope for from certain other arts and history presenters who shall remain nameless, but are to be frequently seen on BBC Four labouring to convey their visceral enthusiasm for their topics through a succession of upbeat “wow” moments and accompanying intonations that leave you hoping they aren’t doing themselves any lasting medical damage in the process.)

The Story of Film promises an intriguing journey running every Saturday night through until nearly Christmas, with Cousins no doubt continuing to play off his belief in cinema as an art form of passion and ideas against its reality in the multiplex age. Cue the likes of Avatar and it’s clear that the process of innovation certainly hasn’t stopped – but where exactly may it be going? I find its subtitle, An Odyssey, no less intriguing, with its hint that it’s a journey that leads back to a home, wherever that has now become. Or maybe, per Thomas Wolfe, “You can’t go home again”?

- Watch The Story of Film on 4oD

Find The Story of Film on Amazon

Find The Story of Film on Amazon

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

The commentary is absolute

The commentary has an Irish

A rare fantastic TV series

Although Mark Cousins' voice

Passion? What passion? He

What should be a fantastic

amazing story indeed very

amazing story indeed very well written and made as well.

The first part showed on TV

This documentary is

It's not his accent that is

Just brilliant! absolutely