Blu-ray: Naked | reviews, news & interviews

Blu-ray: Naked

Blu-ray: Naked

Mike Leigh's howl of millennial dread and existential self-loathing

Naked (1993), the fifth and finest feature film written and directed by Mike Leigh, remains a searing, eerily prescient look at Britain on the verge of a social and economic breakdown.

Maybe even a verbal breakdown, too, for Leigh, unlike any other filmmaker, has an ear for drawing out compelling characters from their distinctive modes of expression. Where so many other British films draw obvious lines between class with emphasis on accents, Leigh’s characters have an inimitable way of winding up words until they shatter.

Though Leigh’s work – which spans 56 years of stage, television, and film – is rightly known for its focus on working class life, Naked is more about the underclass. Nearly everyone on screen is out of a job or underemployed. If not actually homeless, they’re in between spaces, subletting, flat-sitting, or on the run. The protagonist Johnny (David Thewlis on his breakout performance) is first seen raping a woman in a Manchester alley. He steals a car and flees to London in hope of crashing with his estranged girlfriend, Louise (Lesley Sharp).

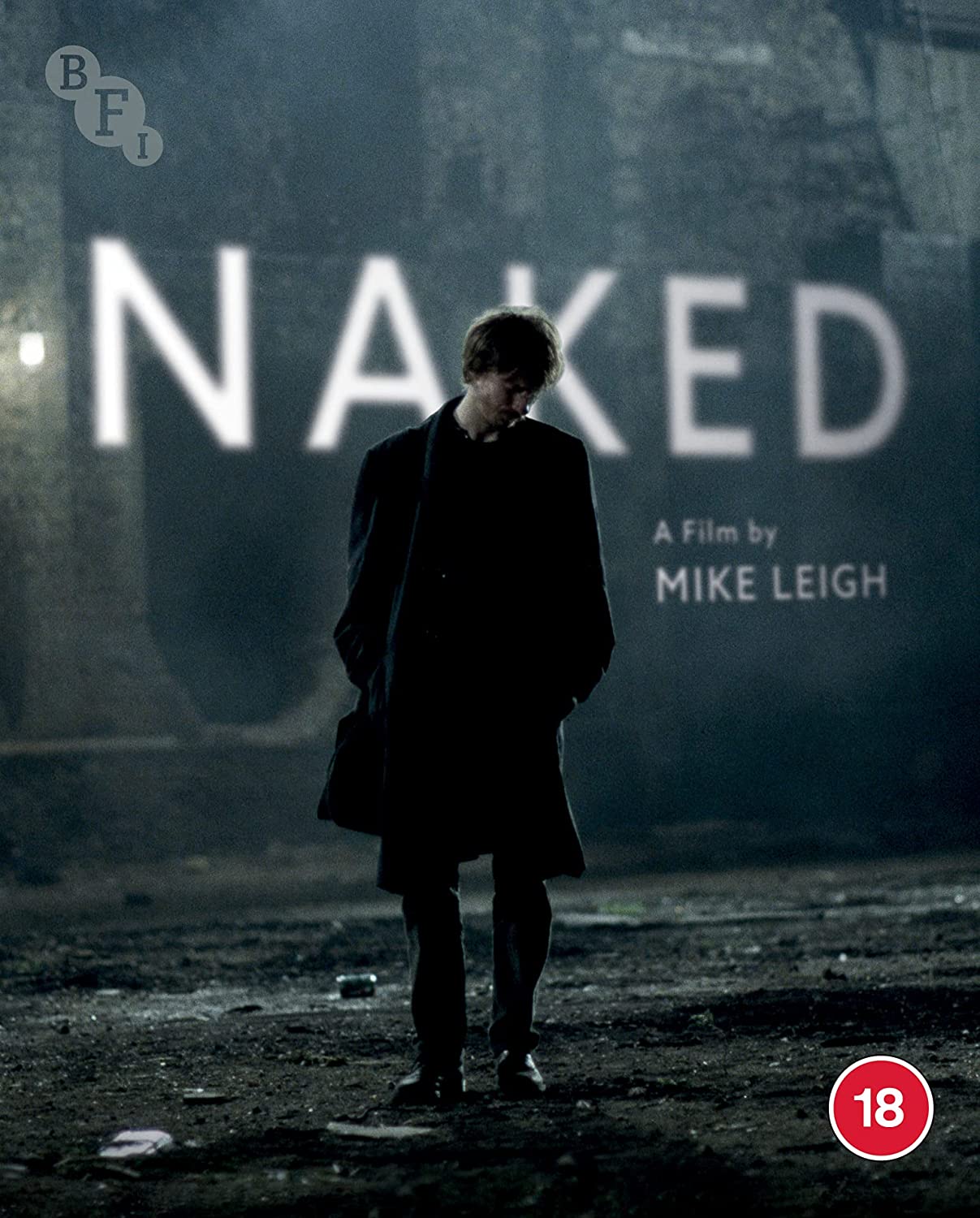

Despite that nasty introduction, Johnny, with his wolfish smile and loping gait, demonstrates off-kilter charm and a brain that’s half first-year philosophy student, half Q-Anon. Sophie (Katrin Cartlidge, heartbreaking), Louise’s fragile roommate, succumbs to it. So does a lonely night watchman at an empty office in a sequence that has the two men sparring over everything from reincarnation and sex to the end of the world. When Johnny lands back outside after dark, though, Naked’s tone goes from black comic to bleak. (Pictured above: Katrin Cartlidge)

Despite that nasty introduction, Johnny, with his wolfish smile and loping gait, demonstrates off-kilter charm and a brain that’s half first-year philosophy student, half Q-Anon. Sophie (Katrin Cartlidge, heartbreaking), Louise’s fragile roommate, succumbs to it. So does a lonely night watchman at an empty office in a sequence that has the two men sparring over everything from reincarnation and sex to the end of the world. When Johnny lands back outside after dark, though, Naked’s tone goes from black comic to bleak. (Pictured above: Katrin Cartlidge)

The farther Johnny roams through streets and disused railway yards, the more Naked seems to paint London as a dystopian nightmare. Nightmarish, too, is the indoor environment: Louise sublets the attic flat in a creepy neo-Gothic house, where acute angled ceilings seem to close in on the inhabitants. Cinematographer Dick Pope used the bleach bypass film processing technique that Roger Deakins created for 1984. Bright colors, especially reds, fade away, leaving shadows blacker than midnight. Even clear skies look ashen.

With everyone he meets, Johnny zeroes in on their weak spot. He needles, teases, instigates, forces conflict. Rivalry between the women comes first as the women spar over his affection. Then a wild card arrives at the flat: a creep named Jeremy (Greg Crutwell) claiming to be the landlord. Violence is inevitable. In Naked’s crumbling London, critics found an easy reading of the film as a critique of Thatcherism, a system pure capitalism and stratified wealth that encouraged those at the bottom to turn against each other and vote against their own interests.

But the movie’s gender warfare is more revealing, particularly when Jeremy terrorizes the women. The attack ends only with the unexpected arrival of the leaseholder, Sandra (Claire Skinner), whose exasperated, almost post-grammatical reactions are pure Leigh. “Can you? How can you?” Sandra fumes “I fail to...It really is beyond me the way you girls choose to live your lives. It just boggles.”

Early critics shamed Leigh for depicting passive female characters, a charge he dismisses as a “radical feminist” viewpoint in a new interview included in the BFI Blu-ray. Though Leigh’s right to argue that depicting misogyny is not the same as being misogynist, his enduring defensiveness suggests a blind spot. His explanation that actresses “were not coerced” into appearing nude belies a willful ignorance of his own industry.

Early critics shamed Leigh for depicting passive female characters, a charge he dismisses as a “radical feminist” viewpoint in a new interview included in the BFI Blu-ray. Though Leigh’s right to argue that depicting misogyny is not the same as being misogynist, his enduring defensiveness suggests a blind spot. His explanation that actresses “were not coerced” into appearing nude belies a willful ignorance of his own industry.

In the film’s sex scenes, the camera lingers on female nudity. True, Thewlis is naked, but he's modestly shadowed whereas Cartlidge’s breasts are front and center during a rape scene (fellow actress Deborah Maclaren's body almost gets star treatment). Moreover, a still photo from the rape scene, with black lingerie Photoshopped in, became central to the movie’s promotional campaign. In those two instances, Sophie is there for her to-be-looked-at-ness. Leigh, who says he does not point audiences in “emotional directions", has a lot to answer for.

Yet that is the sole aspect of Naked that has not aged well. As with his most surefooted cinema work – Topsy-Turvy, Mr. Turner, and the underrated Career Girls – Leigh brings you so close to his characters, you can feel the rattle of their tea cups, the heaviness of their steps on the stairs, as they ponder their next moves in an unforgiving world.

And Leigh continues to forge his own path after decades of incendiary filmmaking, even if he cannot easily find backing. (He recently said that Netflix declined to fund his latest project.) No journeyman gigs for him. If he ever did take on a glossy HBO drama, the result wouldn’t merely be an overhaul. He’d blow the damned doors off.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Comments

Brilliant piece, Justine. A

Brilliant piece, Justine. A really fine piece of writing, on Leigh's best film so far, and the film that established David Thewlis as a great actor!