Haas Hommage à Bridget Riley, London Sinfonietta, Lubman, QEH review - vibrant abstraction | reviews, news & interviews

Haas Hommage à Bridget Riley, London Sinfonietta, Lubman, QEH review - vibrant abstraction

Haas Hommage à Bridget Riley, London Sinfonietta, Lubman, QEH review - vibrant abstraction

Big commission complements a great Hayward Gallery exhibition to near-perfection

Music and visual art, at least at the highest level, should go their own separate ways; put them together, and one form will always be subordinate to the other. A composer being inspired by an artist's work, or vice versa, is something else altogether.

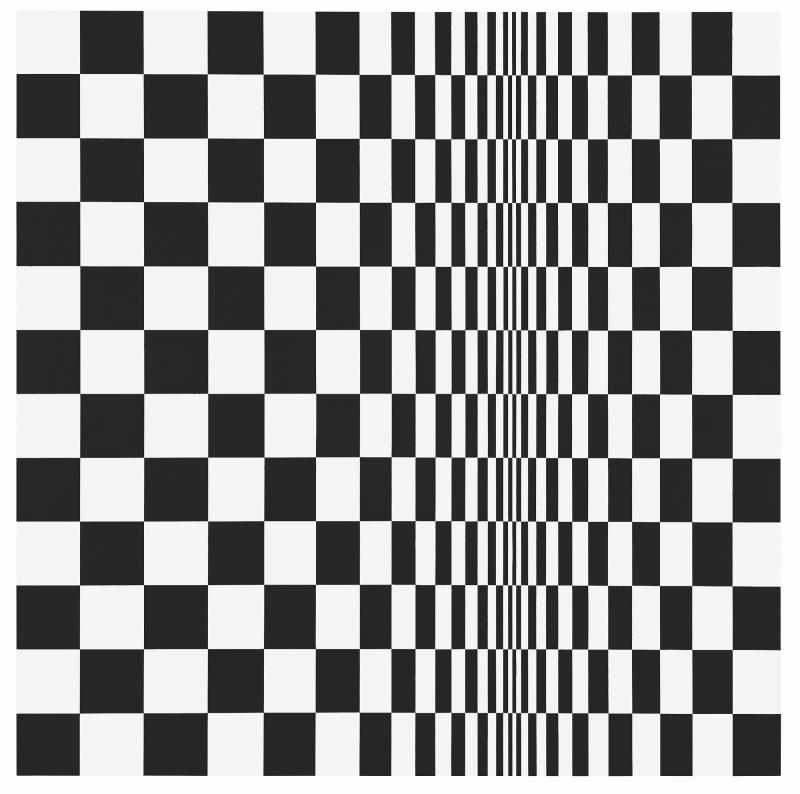

Any comparison will only be analogous – interestingly, Riley gives musical titles like "Paean" and "Aubade" to some of her works – but they do share much in common. In neither is the abstraction bloodless, static or merely intellectual (Riley broke the mould with what she called "conscious intuition" in the op art of the 1960s without study of optics or deeper knowledge of mathematics). Shapes shift in the vortex, surface busy-ness may yield to calms at the eye of the storm, response can be surprising – the difference between the two being that, as you spend time looking at a Riley, the point of greatest intensity can be anywhere within the experience, while in Haas' canvas the frissons are fixed in time by the composer. What Haas (pictured below by GM Castelberg) says in the short film we saw before the performance, “it seems to be repetitive, but it is not," is equally true of his music, where microtones merely increase the expressive possibilities.  And the work is full of colour, which you might paradoxically say of Riley’s earlier black and white assaults on the optic nerve. Even so, I’m not sure I would have chosen the celebrated Movement in Squares of 1961 (pictured below) as the image to show before – praise be, not during – the performance; though music evokes a different kind of “hearing picture” to any one of the canvases I’d just seen, there would have to be a wide colour palette as equivalent to the Hommage. Nevertheless, Riley’s generalisation of a parallel painting as “repose, disturbance and repose” might be turned inside out to describe Haas’s piece. It starts with buzzing strings at extremes of the register; Haas is not so cruel as to make them play constantly like this for 40 minutes, so fixed sounds emerge; piano and tuned percussion lead in evoking triads, tritones, whole-tone scales which morph very quickly into something else.

And the work is full of colour, which you might paradoxically say of Riley’s earlier black and white assaults on the optic nerve. Even so, I’m not sure I would have chosen the celebrated Movement in Squares of 1961 (pictured below) as the image to show before – praise be, not during – the performance; though music evokes a different kind of “hearing picture” to any one of the canvases I’d just seen, there would have to be a wide colour palette as equivalent to the Hommage. Nevertheless, Riley’s generalisation of a parallel painting as “repose, disturbance and repose” might be turned inside out to describe Haas’s piece. It starts with buzzing strings at extremes of the register; Haas is not so cruel as to make them play constantly like this for 40 minutes, so fixed sounds emerge; piano and tuned percussion lead in evoking triads, tritones, whole-tone scales which morph very quickly into something else.  The playing itself, like Haas’s score, was quietly miraculous in that there were hardly any jagged edges, and sequences which felt like gliding over shifting patterns in water: beautiful, limpid, evanescent. Full credit to conductor Brad Lubman, warmly applauded by the instrumentalists, for making it all seem effortless, and of course to the London Sinfonietta for commissioning the work alongside Southbank Centre and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. In a generous gesture, Haas had been asked to recommend a work by a student of his at Columbia University; Katherine Balch’s New Geometry; but this was a baffling preface in which you could only sense the irregular forms, not the geometry within: remarkable, all the same, for passages on the cusp of audibility, especially in the playing of trombonist Byron Fulcher. There was also a post-interval screening of film responses to Riley and Haas from students of Central Saint Martins; but it made more sense to leave with the sensuality of the main artist and composer still resonating.

The playing itself, like Haas’s score, was quietly miraculous in that there were hardly any jagged edges, and sequences which felt like gliding over shifting patterns in water: beautiful, limpid, evanescent. Full credit to conductor Brad Lubman, warmly applauded by the instrumentalists, for making it all seem effortless, and of course to the London Sinfonietta for commissioning the work alongside Southbank Centre and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. In a generous gesture, Haas had been asked to recommend a work by a student of his at Columbia University; Katherine Balch’s New Geometry; but this was a baffling preface in which you could only sense the irregular forms, not the geometry within: remarkable, all the same, for passages on the cusp of audibility, especially in the playing of trombonist Byron Fulcher. There was also a post-interval screening of film responses to Riley and Haas from students of Central Saint Martins; but it made more sense to leave with the sensuality of the main artist and composer still resonating.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Add comment