This delectable supplement to Chailly's Leipzig Brahms symphony cycle is predictably good. Brahms's early D minor piano concerto sounds like an attempt to compose on an explicitly symphonic scale, a study in snarling, haughty grandeur, but the two serenades are breezy, transparent and extrovert. All musical elements which play a crucial part in mature Brahms, and ones which Chailly so successfully highlights in the symphonies. Haydn and early Beethoven are audible influences, but these pieces already sound entirely individual. The first movement of No 1 is joyous, its folky bare string intervals supporting a rustic horn melody. Chailly is significantly faster than some rivals, arguing that the music never gets going if it's played too slowly. The six movements cohere nicely. Me, I'm in love with the passage for clarinet and bassoon at the start of the Menuetto, and the way in which Chailly handles the string entry 90 seconds in. And that tiny Scherzo, demonstrating in barely two minutes why orchestral horn players love Brahms.

The Serenade no 2 doesn't contain any violins. It's not dark music though – Chailly refers to its soundworld as being one of “pleasant shade”. The flamboyant woodwind writing in the Scherzo sings out as a consequence, though the lower strings shine in the central Adagio non troppo. The final Rondo is one of the most effervescent bits of Brahms you'll hear. A superb CD – intelligent, warm performances of two lovely, approachable works. Decca's seductive engineering adds to the fun.

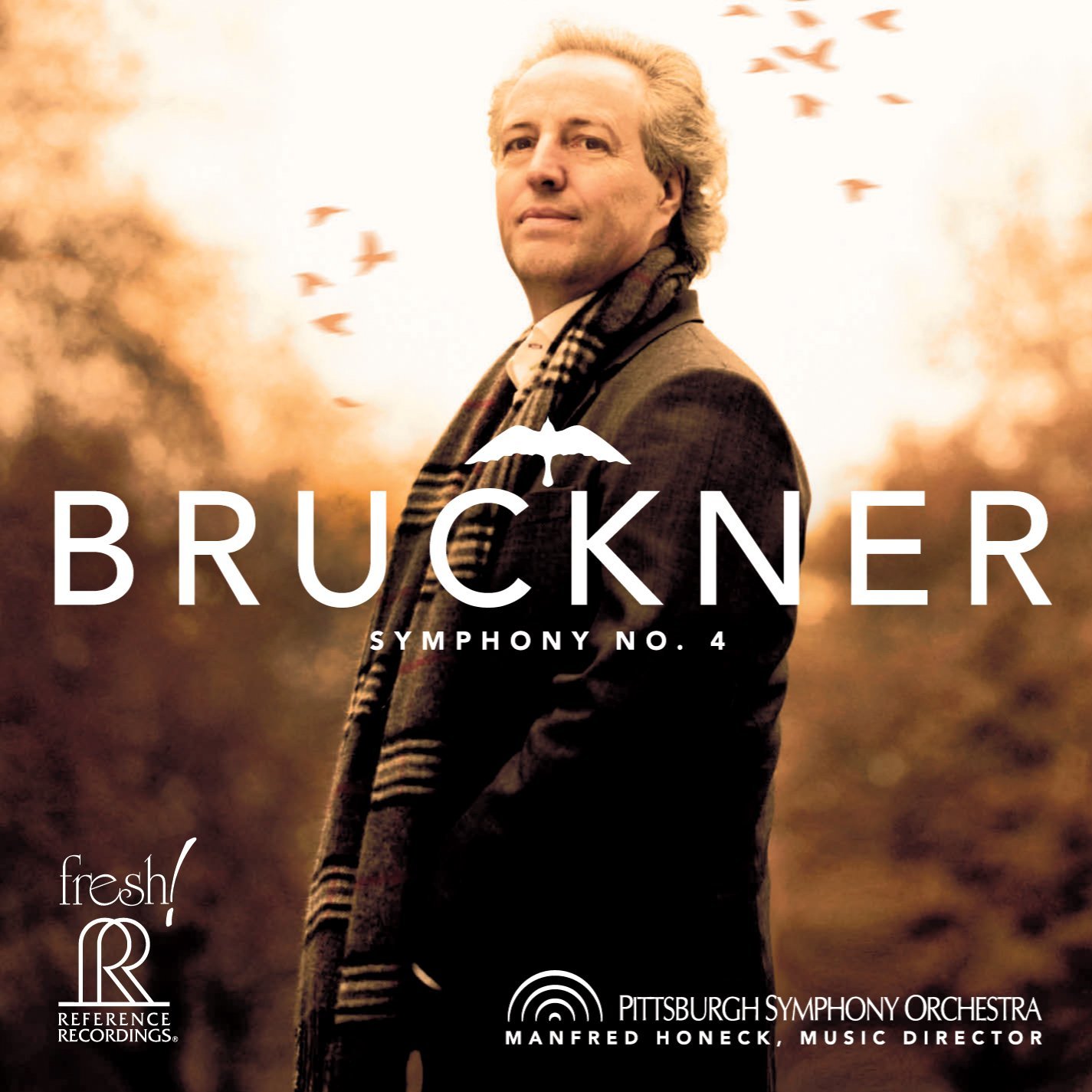

Manfred Honeck's at it again. Changing dynamics, tampering with tempo markings, adjusting balances. But when the results feel so idiomatically right, only a chump would object. Every tweak is explained and justified by Honeck in the sleeve essay. As he writes: “rigorous fidelity to the score has the positive effect of being exact in looking at the notes, but also runs the risk of losing the tradition in which the piece was born.” Conductors with first hand knowledge of the Bruckner tradition took a much more flexible, free approach to his music; idiomatic Bruckner shouldn't just be about pregnant pauses and glacial pace. Honeck sees this symphony as predominantly joyous and secular, the spiritual dimension less overt than in Bruckner's later music. Timings aren't excessively fast, but this performance has irresistible momentum – the first few minutes, from horn call to big tutti, are almost indecently exciting. It's Bruckner reclaimed.

Start noting down the high spots and you'll need several sheets of paper. Sample a wonderful moment 10 minutes into the first movement, the brass dynamics subtly softened so that a viola counter melody can soar out. The coda glows. Bruckner's rambling second movement becomes quirky and endearing. The hunting scherzo is played with flexibility, at a real lick; you can sense the grins on the faces of the Pittsburgh brass players. The naïve Trio has just the right lilt. Honeck's greatest achievement is in knitting together the last movement's disparate elements. Rustic charm and epic drama coexist happily. This is a great performance, exactly the sort of disc that might convert Bruckner sceptics. The live recording glows, and the playing is sensational. More from this source please – the Honeck/Pittsburgh partnership is stealthily producing some of the greatest orchestral recordings in the catalogue.

Quartetski does Stravinsky: Le Sacre du Printemps (Actuelle)

Incredibly, there are at least four competing jazz interpretations of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring on disc, including an implausibly funky big band version and a trio rendition from The Bad Plus. These two recent quintet accounts are fascinating, both technically and musically. Both highlight aspects of the original that it's easy to miss when it's played slickly by vast orchestra forces. Guitarist Eric Hofbauer's arrangement was prompted by his watching a Youtube video of Leonard Bernstein rehearsing the ballet with a youth orchestra, complaining to his percussion section that he can't feel the "prehistoric jazz". Hofbauer does let us feel the jazz, Stravinsky's polytonal harmonies and shifting metres emerging with unmatched clarity. Drums, cello, clarinet and trumpet comfortably cover the orchestral families, and the guitar brilliantly fills in the gaps. Hofbauer understands the score's sophistication, allowing his players to improvise within Stravinskian harmonic constraints. His collaborators are superb – singling anyone out seems unfair, but Todd Brunel's nimble, punchy bass clarinet deserves special praise along with percussionist Curt Newton. Excellent sleeve notes accompany a witty band photo (pictured above), paying homage to an iconic portrait of Stravinsky. It's released alongside Hofbauer's wonderful reimagining of a Messiaen classic, now renamed Quintet for the End of Time.  Pierre-Yves Martel's Quartetski are based in Montreal. They've already reinterpreted Prokofiev's Visions Fugitives and there's a Bartók disc in the pipeline. Martel's approach is looser and more anarchic than Hofbauer's, the ballet recast for drums, electric guitar, reeds and violin. Martel plays viola da gamba, and, tantalisingly, what's listed as "objets divers". The 32-minute original is extended here to nearly 50 minutes. The score's folky roots emerge more strongly, and the improvisation is a lot freer. The extended instrumental solos never outstay their their welcome, and Martel's pungent distillation of the work's essence continually throws up surprises: the wonderful overlaying of duple and triple time rhythms in "Augers of Spring", and the chilliness at the opening of the ballet's second half. Quartetski's "Sacrificial Dance" is a freer, spookier affair: drummer Isaiah Ceccarelli pounds out Stravinsky's rhythms against a sustained chords and scratchy vinyl samples, before the music fades out. If you love this piece, don't feel you have to choose between Hofbauer and Quartetski. Buy both.

Pierre-Yves Martel's Quartetski are based in Montreal. They've already reinterpreted Prokofiev's Visions Fugitives and there's a Bartók disc in the pipeline. Martel's approach is looser and more anarchic than Hofbauer's, the ballet recast for drums, electric guitar, reeds and violin. Martel plays viola da gamba, and, tantalisingly, what's listed as "objets divers". The 32-minute original is extended here to nearly 50 minutes. The score's folky roots emerge more strongly, and the improvisation is a lot freer. The extended instrumental solos never outstay their their welcome, and Martel's pungent distillation of the work's essence continually throws up surprises: the wonderful overlaying of duple and triple time rhythms in "Augers of Spring", and the chilliness at the opening of the ballet's second half. Quartetski's "Sacrificial Dance" is a freer, spookier affair: drummer Isaiah Ceccarelli pounds out Stravinsky's rhythms against a sustained chords and scratchy vinyl samples, before the music fades out. If you love this piece, don't feel you have to choose between Hofbauer and Quartetski. Buy both.

Add comment