Things to Come, LSO, Strobel, Barbican review - blissful visions of the future | reviews, news & interviews

Things to Come, LSO, Strobel, Barbican review - blissful visions of the future

Things to Come, LSO, Strobel, Barbican review - blissful visions of the future

Landmark film given the live-orchestra treatment

Last night at the Barbican was my first experience of a film with live orchestra, which has become a big thing in the last few years. The film in question was Alexander Korda’s extraordinary HG Wells adaptation Things to Come, from 1936, imagining a century of the future.

As ever with sci-fi, while it is fun to see what predictions turned out right and which wide of the mark, the main takeaway is what the film tells us about the anxieties of 1936. Things to Come has a notable symphonic score, by Arthur Bliss, the first to be released as a commercial soundtrack album, and the film that first brought the London Symphony Orchestra into the world of cinema.

And it is a very fine score, one which helped to form the template of orchestral film scores, by turns taut and dramatic, but also grand and aspiring. It is perhaps to modern sensibilities a bit odd to have the same musical language accompanying scenes from 1940 and a putative 1970 in which civilisation has collapsed, but it comes round full circle to be very fitting once again for the striving, idealistic ending.

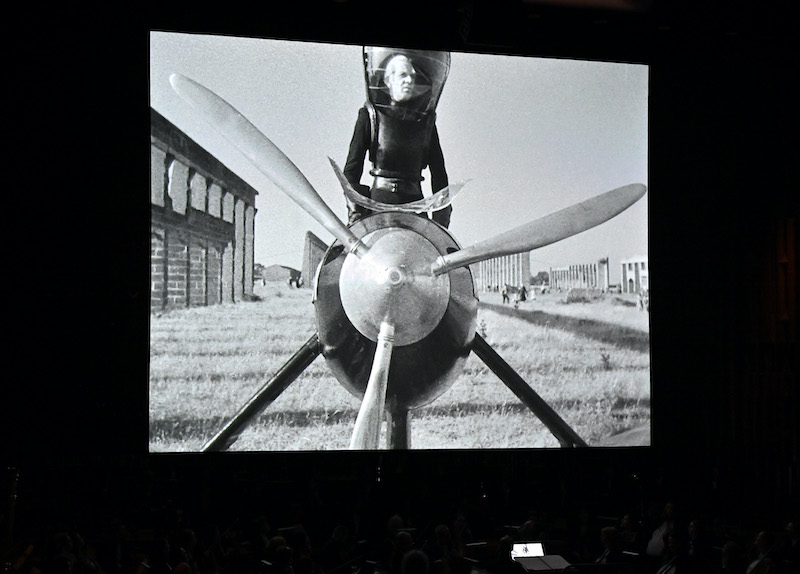

But it’s certainly a technical triumph. Conductor Frank Strobel (pictured above by Mark Allan), for whom this kind of thing is a speciality, did it all without a click track to help him find the tempos, and still made the hit points with a startling degree of accuracy. And this was not at the expense of musicality: the LSO were on fine form, clearly revelling in Bliss’s scoring, and committing fully to the occasion.

The most notable thing about the film is its extraordinary production design, by Alexander Korda’s brother Vincent. Apart from a few awkwardly obviously scale-models, the visuals are stunning for the time, and the transformation of 1930s London into a post-apocalyptic wasteland and then to a futuristic city must have been stunning at the time. The production is also unbelievably ambitious in scale, with hundreds of extras and massive sets. The prediction of a war in 1940 is spot on, although the pervading fears of gas attacks proved unfounded. There is a pandemic and a plan to go to the moon which is imagined for 2036 – reality got there nearly 70 years earlier.

But the inevitable anachronisms aside, I was pleased to see the film and particularly to hear Bliss’s music, which in the rip-roaring “Entr’acte” and the nobilmente final sequence is really very good, and left me wanting to go and discover more of his (nowadays neglected) work.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment