It’s Christmas 1971 in New Prospect, a suburb of Chicago, and pastor Russ Hildebrandt has plans for time alone with Frances, an attractive young widow who’s just moved back into town.

Important facts become quickly apparent: Russ resents his long-suffering wife, Marion, and he has suffered a humiliation at the hands of Rick Ambrose, the groovier pastor (“a little black-moustached satyr with stack-heeled hooves”) who leads Crossroads, the church’s youth group. Ambrose’s way is less God, more sensitivity session, and it goes down a storm with the kids. Even worse, Russ’s teenage children, Becky and Perry, have joined the group, thereby wounding him deeply, and his oldest son, Clem, is threatening to go to Vietnam – anathema to Russ’s pacifist convictions, though Clem sees it as a moral choice to join up in place of someone less privileged than himself. He also wants to spite his father.

The five Hildebrandts' stories are told in alternating chapters. All are preoccupied with goodness, sin and the possibility of a divine presence. Becky, the high-school queen bee, feels it after smoking weed for the first time. No one is better than Franzen at portraying the paranoia and circuitous thought processes of the terribly stoned person. “In her mind’s eye, her thoughts were laid out like snacks on a lazy Susan. They weren’t evaporating the way thoughts were supposed to. They just sat there, going round and round, available for second helpings.”

Later, taking refuge in front of an altar, Becky’s circle of hell gives way to a golden light that she sees as a glimpse of God, or pure goodness. No glimpse of goodness for Russ though, getting stoned with Frances, as he listens, filled with terror, to Robert Johnson, and sees himself as a phoney, part of the fraudulent white race of “parasitic wraith-people”. It’s odd, muses Russ at a later point, that self-pity isn’t on the list of deadly sins: “None was deadlier.”

Their younger son, the precociously brilliant, 15-year-old Perry (he bears some resemblance to the condescending Joey in Freedom, Franzen’s less absorbing family-saga novel of 2010) is an insomniac addict and a high-school drug dealer who operates “at a level of rationality inaccessible to others”. His deviousness and manipulative powers extend to the youth group, where hugging, sharing and crying are prime currency.

By the time his older sister Becky, with her perfect teen-girl hair, joins the group, he’s mastered the game of Crossroads, realising that instead of avoiding the socially uncool you sought them out, “making sure, of course, that you were noticed doing this” and instead of comforting a friend with fibs, you told them unwelcome truths.

Because it’s a game, he’s good at it. But Ambrose, disappointingly, isn’t fooled and realises, as Becky tells Perry when they’re thrown together in a truth-telling "dyad", that Perry is trouble. Just how much trouble, and how devastating the consequences are for the family, becomes clear towards the end of the novel, as does how very unwell mentally Perry is – “a problem with the entire circuit board”, as one of his friends puts it after Perry starts bingeing on cocaine and speed on a cataclysmic Crossroads work camp in Arizona.

Perry uses everyone, even his charming little brother Judson whom he loves and with whom he shares a room. But Becky’s impressive truth-telling propels him to try to become a better person. In the process, he ends up at a tedious church Christmas party, where he drinks too much gløgg and impresses a rabbi and a priest with his sophisticated questions.

Can goodness ever be its own reward, he asks them, or does it always serve “some personal instrumentality”? (He does have a tendency to talk like Frasier.) This Catch 22 – that there’s always some self-serving angle involved in being “good” – is also a preoccupation of Russ, not that virtue informs his behaviour towards Marion while he’s still obsessed with Frances, the self-regarding widow.

Marion’s story is as compelling as Perry’s. Until page 129, we only glimpse her role as a dowdy, dutiful pastor’s wife who writes Russ’s sermons and is a mother of four. But beneath lies a surging rage that dates back to an unstable past in LA involving her father’s suicide, an obsessive affair with a married car salesman, an abortion, and a dazzlingly well described psychotic break. She’s only given a sanitised version of these events to Russ.

Now, spurred on by Russ’s affair, she’s reached a crossroads of her own. This is 1971 so she begins her reinvention by deciding to get thin, which she does through a diet of Lucky Strike cigarettes, aiming “to glow white-hot with the burning of her fat false self”. She decides that her dumpling-like therapist is useless, apart from the free samples of Quaaludes she doles out, as is her marriage to Russ.

Russ’s recklessness with Frances is bound up with the fact that Marion had sex with someone else before she married him and “he could not tolerate her superiority in this regard”. Hardly endearing, but convincing, and his strict Mennonite background and rigid Anabaptist pastor father have a lot to answer for (this flashback section, the most earnest in the novel, is almost a short story in itself). Russ is a curious mix of cluelessness and capability (he’s a dab hand with a wrench). I’m longing to know what he and the other Hildebrandts do next. Bring on volume two.

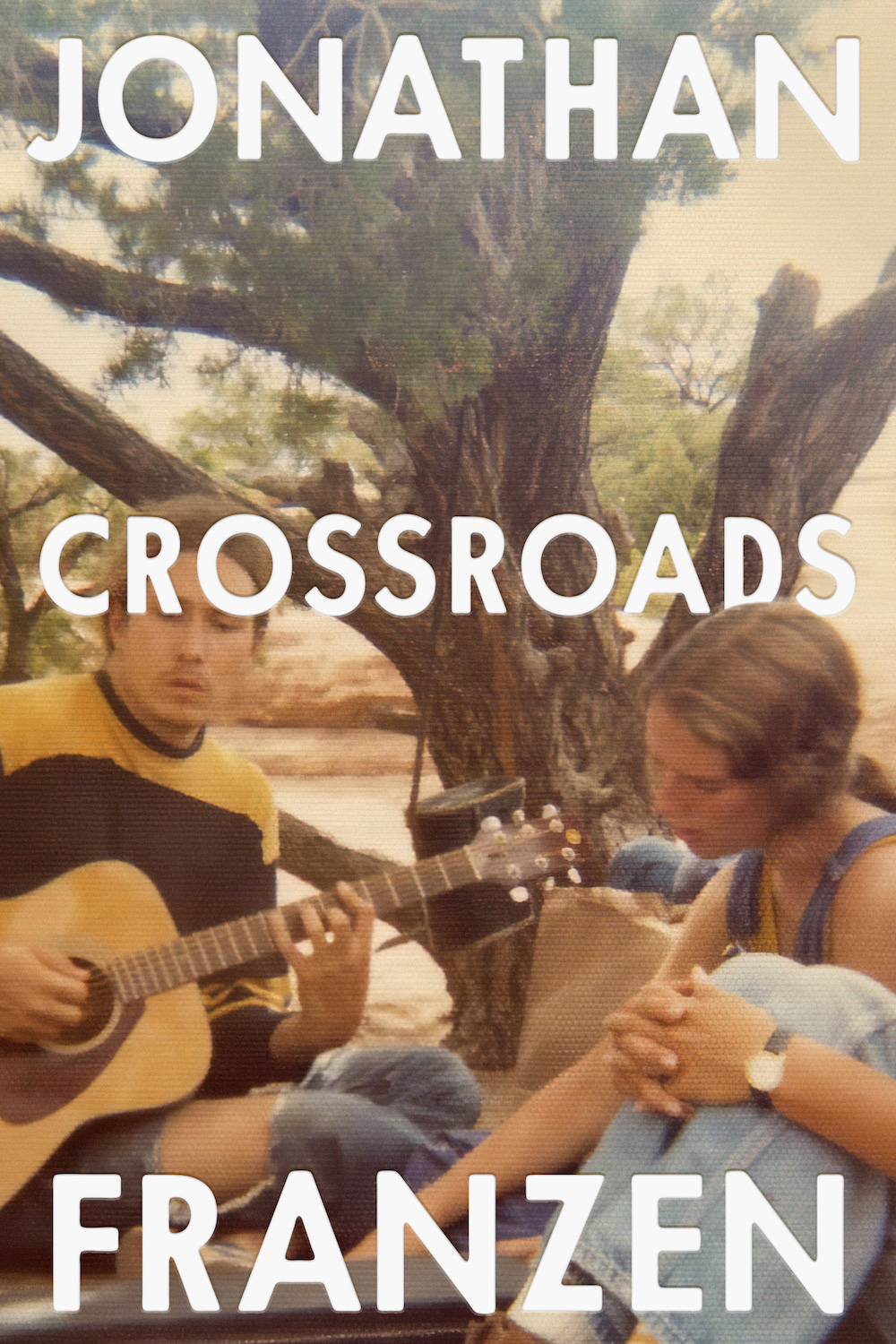

- Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen (4th Estate, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment