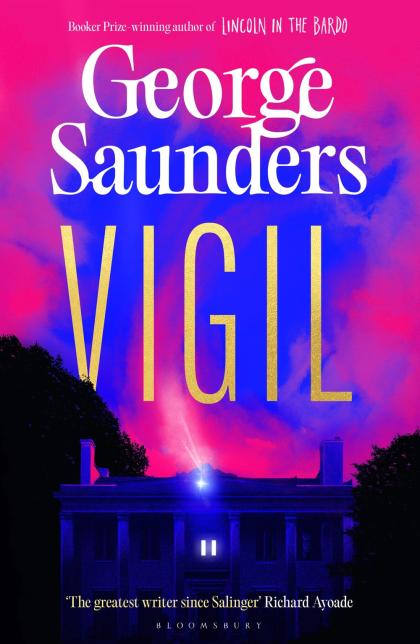

Is this person dead? It’s a wise question to ask yourself when reading George Saunders. In his Booker Prize-winning Lincoln in the Bardo, the answer doesn’t arrive until page three, where the narrator first mentions his confinement in a “sick box”. Not so with his new novel, Vigil, which opens:

'What a lovely home I found myself plummeting toward, acquiring, as I fell, arms, hands, legs, feet, all of which, as usual, became more substantial with each passing second.'

In life, Jill "Doll" Blaine was a limited woman, capable of directing her love only toward “those precious few with whom she had randomly been placed into proximity, i.e., friends, family, husband.” Death explodes these limits. Jill can suddenly read people’s thoughts, feel what they’re feeling, and see where they came from. She finds herself charged with a cosmic vocation: bringing “comfort” to the dying and guiding them gently into the next life.

Her new “charge” is K. J. Boone, an oil executive with only hours to go. Jill sets about her task for the 343rd time, only to find it unusually complicated, first by the resistance of Boone himself, then by the arrival of others “of her ilk.” It seems that Boone has long been a talented advocate for the status quo, that he wielded an outsized influence on the world, and that he now stands accused “of something. Something involving the weather.”

What follows is a little Dickensian, only here Scrooge is already a signed-up member of “the black crepe club,” and the ghosts haven’t agreed on a line of attack. What can they hope to achieve? It is too late to change anything. Boone can only sign off on his record. Repent or double down.

At first, Jill doesn’t think any of this is relevant. She knows what Boone is, and she’ll try to comfort him anyway. Able to (quite literally) step into another’s shoes, she has come to understand that a person is so limited by disposition and circumstance that their actions are virtually inevitable. Everyone is comprehensible, and therefore everyone is forgivable. She’s a bit like God. Or rather, she’s a lot like a novelist.

Soon, however, her composure is threatened by her charge’s odiousness. The reader is prompted to ask how inevitable Boone, as he stands, really was. Can comfort be the greatest good if it requires us to smooth over serious harm? What if the comfort we prize is itself predicated on this harm? It all hinges on how much Boone knew, and as Jill descends through the strata of her charge’s ego, her sense of “elevation” begins to slip.

Vigil has everything you might expect from Saunders: amateur haunting, physical comedy, and a chorus of distinctive voices. Once again, he imagines an afterlife where some believe, and some do not, where the dead realize all too late “how unspeakably beautiful all of this was,” and where there is no supervision, no vindication, no way back. In Lincoln in the Bardo, these features reflected the bittersweet experience of life and loss. Here, they challenge the belligerent faith espoused by some on the American right, who feel sure that God is with them – that might is right:

'He was going home now, to God, his dear God, who’d always loved and protected him and made good things, all the best things, happen for him. Thank you, Lord, thank you for making me who I was and not some little squirming powerless nincompoop.'

But a novel’s virtue is largely unrelated to its merit as a work of fiction. Vigil is slighter than Lincoln in the Bardo, but somehow more general. Boone stands in for a whole industry, and his speech borders on burlesque: “he’d lived an extraordinary life, full of tremendous accomplishment, and had always done his best and, in sum, had done nothing wrong, not a goddamn thing, and was leaving behind no lasting harm, zero, nada, none at all.” Saunders humanises him with a little backstory (small town, scrappy, running from the memory of hardship), yet the character feels retrofitted to argument. The book lacks the emotional gravity of its predecessor, which revolved around a father grieving his child. In fact, it lacks any compelling (living) characters.

In this sense, Vigil is something of a “problem” story or fable, compressed and singular in focus. It reads as direct engagement with an allegation sometimes levelled at Saunders – that his writing is too humane, too ambiguous, too funny to effect any change. But admirers of his work, particularly of his short stories, would never have made this complaint.

Jill’s struggle to sustain her dispassionate empathy seems to reflect Saunders’ own worry that our urge to empathize is a morally sterile indulgence, one easily exploited by cynical actors. Vigil is most interesting in passages where Jill is challenged not by Boone, but by intoxicating reminders of her own past. They convey the simple truth that we must act rightly, not because there will be a reckoning, but because life is precious. Yet there is an uncharacteristic bluntness to the writing, as if Saunders fears this truth might go unrecognised. Time reveals all, but Vigil worries that there’s no time left.

- Vigil by George Saunders (Bloomsbury, £18.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment