10 Questions for art historian and fiction writer Chloë Ashby | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for art historian and fiction writer Chloë Ashby

10 Questions for art historian and fiction writer Chloë Ashby

On sights, acts of seeing and book 'Wet paint', inspired by Manet’s 'A Bar at the Folies-Bergère'

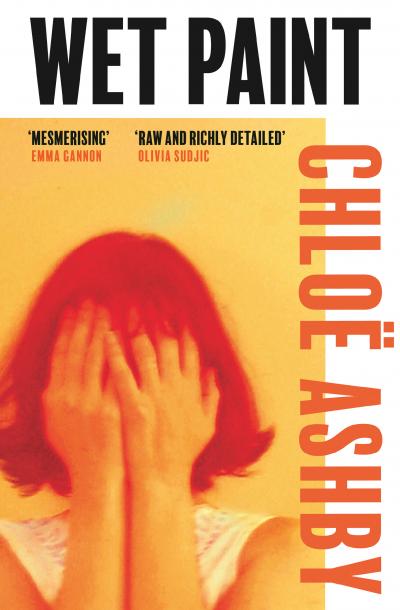

“Is she at a pivotal point in her life but unable to pivot…?” Eve, the young heroine of Chloë Ashby’s dazzling debut novel, Wet Paint, asks this question standing in front of Édouard Manet’s painting "A Bar at the Folies-Bergère" (1882). Yet she could easily be asking herself the same question.

Unable to “pivot” in life, but at a pivotal stage, Eve goes from job to job, is thrown out of her flat, becomes increasingly reckless and then spirals downwards in an effort to stave off the memories of the past. Initially, art – the viewing and co-creation of it – keeps her afloat, but past traumas soon catch up with present ones and she must confront her loss before it is too late. The book is a warm yet challenging coming-of-age tale: Ashby paints a beautifully vivid portrait of a resilient young woman coming to terms with how to survive in a shifting, hostile world.

In a café close to the Courtauld, the gallery in which the Manet painting hangs, I caught up with Ashby to discuss the importance of visual art to her writing. We talked about acts of seeing and being seen in Wet Paint and the strength of her first-person narrator, Eve.

Like Eve, you’re an art historian. But you’re also an arts writer and cultural critic. How did these different practices and writing genres inform Wet Paint?

Like Eve, you’re an art historian. But you’re also an arts writer and cultural critic. How did these different practices and writing genres inform Wet Paint?

I was definitely aware of these disciplines as I was writing the novel. Arts criticism is very visual, and when I’m starting a review or an artist interview, I’ll often begin with a visual cue or by describing a particular work. When it came to the process of writing the novel, Manet’s painting, "A Bar at the Folies-Bergère" (1882), gave me a similar anchor. Beyond the painting itself, I’m a fairly visual person and I’m sure this comes across in the writing. I’ve passed it on to Eve, too, who, as you know, is always observing things around her.

Sight and acts of seeing – whether it be the absorbing observation of a work of art or the "skin singeing" gaze of others – are integral to the narrative and Eve’s experience. Could you talk more about the power of looking in the book?

The idea of seeing and being seen is something I have thought about and written about a lot. Even at university, when I wrote my dissertation on French artist Gustave Caillebotte, it was important. Caillebotte’s painting, "The Floor Scrapers" (1875), depicts three half-dressed workmen in a bourgeois Parisian interior, and this act of a man looking at the male form is unusual for a time when lots of male artists were painting women. Today we’re so used to going to a museum and being faced with countless female nudes painted by men. This form of looking has always been at the front of my mind.

I also wanted to articulate that disconnect between the way we look and present ourselves to the world, and the way we feel. Partly because it’s an experience many of us are acutely familiar with, but also because it’s something I’ve always thought about in relation to Manet’s painting. We’re presented with this barmaid, Suzon, who has a very enigmatic expression, and there’s no way of knowing what’s going on in her head.

One of the reasons I wanted Eve to be a life model was because that’s a situation in which the dissonance between how you feel and how you appear is heightened. She steps into the studio and literally lays her body bare. When she’s in a pose, she’s completely still and silent, and yet her mind, unbeknown to the artists, is racing.

It would be good to hear more about Eve’s life modelling. Initially, I felt like Eve was relinquishing her power and privacy, but actually it was a brave and, at times, empowering activity. Was it intended to be a form of empowerment?

Yes, definitely. In the beginning, her becoming a life model is a bid for empowerment; it’s her taking control. She’s excited by the thought that all these strangers are taking time out of their day to come and look at her, and it makes her feel good: seen and appreciated. But then, very quickly, she realises that what they’re seeing is not really her, and she says, at one point, that to them she’s little more than a collection of sketched lines or a bowl of fruit.

What’s ironic is that the looking that goes on in the life-modelling studio is more objective. It’s a safer and less charged kind of looking than that which happens to women on the street or what Eve encounters with leering regulars at the restaurant. To begin with at least, Eve is safer in the studio, completely naked, than she is out in the world fully clothed. In a way, the novel is about the power of art; the way it can speak to your pain and carry you when life and language fail to. For Eve, her relationship with Manet’s Folies-Bergère has a special hold on her. Could you talk about why you chose this painting?

In a way, the novel is about the power of art; the way it can speak to your pain and carry you when life and language fail to. For Eve, her relationship with Manet’s Folies-Bergère has a special hold on her. Could you talk about why you chose this painting?

I studied at the Courtauld and vividly remember the day I saw Manet’s painting in the flesh. Since then it has been a companion to me – though not to the degree that it is for Eve! Anyone who has stood in front of the painting will understand there is something powerful about the gaze of the barmaid, Suzon. For a very long time I didn’t make it past her face, because, as I mentioned before, I was so preoccupied with trying to figure out what she was thinking: was she tired or bored at the end of a shift? Was she lonely? This is partly why the painting is also so captivating for Eve; much like with Suzon, she couldn’t tell what her best friend was thinking before she died. And those closest to Eve can’t tell what she’s thinking and feeling either. She’s so conscientious about keeping her thoughts and feelings hidden.

Manet’s painting is known for its play on perspective via the mirror. It occurred to me there’s a lot of mirroring, reflection and deflection occurring subtly in the book, too. Was this intentional?

Manet was criticised for the mirror in the painting, as it doesn’t make sense: for instance, Suzon is not standing where she should in the reflection. Some people thought he’d made a blunder, but to me it’s a nod to the instability and weirdness of modern life. The mirrorings and reflections (between characters and circumstances) in the novel were something I was conscious of from the start. As Eve goes through the novel, she “borrows” other people’s belongings, trying on different guises to see how it feels to “be” them. It’s another way for her to escape the thoughts churning around inside her head.

I wanted Eve to be in this hazy mid-space between education and adulthood, which is an exciting time, a coming of age, but also unstable. You’re desperately trying to figure out what you want to do and who you want to be. And for Eve, there’s an added trauma which means she’s teetering on the edge. That mid-space is one of mirrors and it’s a very disorientating space to find yourself in.

Eve is such a strong narrator. She has a vibrant sense of the world around her, a painterly way of seeing and making life. Yet, juxtaposed with this compelling mode of observing and relating to the outside world is her extreme vulnerability in it. Even before she begins life modelling, Eve is vulnerable to predatory men and more broadly to the desires of others. I wondered if you could talk a bit more about this dichotomy in the character.

We are so often pigeon-holed – you’re either strong or you’re vulnerable – and one of the things I wanted for Eve was to give her room to be both – and more. She is incredibly strong, considering what she’s been through with her family and Grace, but also in the way she is and how she holds herself – I admire her. Sometimes that strength sees her being spiky and reckless, but she also has a softer, more vulnerable side. Often that side is brought out in unexpected ways, like when she’s with Molly, this sweet six-year-old girl who she looks after. Eve is seemingly anti-“having children”, but something about Molly enables her to tell the truth. Again, like with Max, it’s the people who treat her the way she deserves to be treated that she’s able to be the most vulnerable with.

And lastly, what do you hope young women will take away from reading Eve’s story?

I hope the book provides recognition and light relief. Recognition of unspoken anxieties and sadness, the way women are looked at in life and art, and some of the things that happen to women every day, which we feel it’s easier to shrug off. I hope the novel makes young women feel seen. But I also hope it’s entertaining, that Eve is a fun person to spend time with, as well as being a person you want to shake, give a hug to or shout at – all of those things we feel towards a close friend.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment