theartsdesk Q&A: Amina Cain on her first novel and her eternal fascination with suggestion | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Amina Cain on her first novel and her eternal fascination with suggestion

theartsdesk Q&A: Amina Cain on her first novel and her eternal fascination with suggestion

The American writer discusses 'Indelicacy' and characters who are flawed and unfixed

Amina Cain is a writer of near-naked spaces and roomy characters. Her debut collection of short fiction, I Go To Some Hollow (Les Figues, 2009), located itself in the potential strangeness of everyday thoughts and experience.

Jessica Payn: I’d like to start by asking about paintings: Indelicacy is a book compelled by the narrator’s desire to write about them – not with any defined aim; not to explain them, but to notice them, and translate their signs into a parallel set of verbal signifiers. Why would you say Vitória is so drawn to them, and more generally, to inhabit what she sees?

Amina Cain: Vitória is drawn to the paintings for that very reason, because she wants to inhabit them, wants to go inside. In them, she sees life that has been absent from her own lived experiences, but that she recognises, and to which she feels great kinship. In a way, they match her interiority. And in looking at them she is taken over by a kind of aesthetic experience. She begins to see the world around her in terms of aesthetics too. What is in a room can be as satisfying as what is in a painting, and looking at paintings is what allows her to pay attention to what she sees in her own settings and landscapes, and for it to transform her life.

It’s also a novel steeped in the politics of the gaze. The word "look" is one of its most insistent, bringing to mind John Berger’s famous remark that “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” How would you define the tensions between visibility and invisibility, observed and observer in the book? It occurs to me that the structure turns Vitória into a viewer (as well as narrator) of her own life, which is synonymous with her authority over the text. She knows, and so controls, what will unfold.

The tensions between visibility and invisibility are especially present, I think. Early on in the novel, Vitória is looking all around her, but people aren’t always looking back, in large part because of her economic class and station, but also because she is a woman. But it doesn’t stop there. Later she realises she treats people at times as though they are invisible too, doesn’t see them. And, as a woman, especially once she marries into money, men look at her continuously, which she tries to curb with sharp words. Additionally, as you say, she becomes a viewer of her own life. She is always looking at it. I don’t know if she completely controls it, necessarily, though she does try.

To describe art, as Vitória does, is also to engage in ekphrasis. Art historian W. J. T. Mitchell has drawn attention to the gendered logic that underlines this device: “the poet, speaking for the world of masculinity, action, and narratives, insists (or desires) that the work of art is spatial, female, and mute” (Theresa M. Kelly’s summary of his argument). This logic is interestingly complicated by Vitória’s status as a woman writer whose use of ekphrasis never quite does enough narrative in the book – that’s to say, not enough for us to be confident of the meanings we are meant to take from her writing. On one of the two, juxtaposed portraits of the Virgin Mary, she thinks: “The figures of the living look just as dead as the man who is meant to have been killed.” How do you see these logics playing out?

When Vitória describes a painting she sees, it isn’t to tell a story of it, or even a story about her life, but is a way in. She is dreaming her way into that space, composing a new reality. It is how the border between a painting and her life grows thin. And in the act of engaging in this kind of ekphrasis again and again, the border perhaps begins to dissolve. To describe the paintings is a form of experience for her, and I hope an experience for the reader as well. I want the writing to conjure what it’s like to encounter art. I think that on some level at least, Vitória leaves gender behind when she looks at and writes about art. For her, it is beyond gender. Yet, in other ways it isn’t. She isn’t trying to master the art she sees, after all, but simply wants to engage with it.

I feel like it’s also very important to talk about temporal eeriness: Indelicacy is haunted by suggestions of time and place but never gives enough context for the reader to locate the narrative within a specific history or culture. Much of it is set in one city (otherwise in the countryside) and the protagonist and her husband (who is another blank, never named) visit “the desert” and “the ocean”, where those definite articles are determinedly vague. This feels at one with the candlelight that suffuses the book, part of its withholding, painterly quality: soft outlines suddenly dropping into darkness. Could you talk about your decision to set the book in this way? It’s been called timeless, but there is a definite sense of the past – an interest in the limited roles available to women then, and to those weren’t wealthy or upper-class – even as that historicism is uncanny, opaque.

I love that. The withholding, painterly quality of the candlelight, and soft outlines dropping into darkness is so nicely said. It was less of a choice to set the book in an undefined time and place, and more of a compulsion to create a setting that was suggestive rather than stable, that flickered with possibility without being nailed down to it. When I began the book, I saw images in my mind, and objects from the past, and so it was a matter of composition, in a way, of a setting and an atmosphere, and by extension, a time. I think I was trying to make my own pictures rather than make anything “real.” Of course, as you say, the narrative depends to a large extent on a notion of the past. That’s where many of the limits in Vitória’s life come from, especially in terms of gender. And yet, many women face those restrictions still, or at least traces of them. There is, unfortunately, a sort of timelessness when it comes to the restraints that have been placed on women.

There’s also more to say about the book’s painterliness, which is part of the luminous, pared back quality of the prose: what is represented, what the character Vitória reveals, feels very carefully limited, and this brought to mind the idea of composition and how that might describe the novel. A set of objects in stark relief. Was this part of your editing process, cutting words until a limited number of objects and observations, or even a limited vocabulary, was left?

This describes exactly what I wanted the book to be: a set of objects in stark relief. That isn’t all of it, of course, but certainly how I took up imagery and setting and sometimes character. I worked from a place of minimalism from the outset, but still cut a great deal when editing. A few drafts in, I cut half the book, sometimes in big swaths, sometimes a single word in a single sentence. I’ve always felt the desire to put objects and details in relationship to each other, and for me it only feels like I can do that if there is space around them, if things don’t get too cluttered. And it seems like the way for them to really be seen, to be visible.

Relatedly, it would be interesting to know whether the writing process Vitória describes is similar to your own? Letting “innocent” thoughts collect in a notebook.

My writing process is, in many ways, quite different from Vitória’s. I’ve never been one to keep a notebook, except for more recently, in the last year. And though writing can indeed be difficult for me, I don’t think it’s as hard as it is for her. In Indelicacy, Vitória is coming to writing, and finding her calling/vocation in life, and I suppose the novel is as much about that as anything else, of discovering new things and trying to figure out how to channel it all through her writing. But that line about words innocently sitting on a page not knowing yet what is meant to surround them feels true for me, and the desire to go further into something, into experience itself, and into my writing, does as well.

I love the title, which is very apt. “Indelicacy” is a word that contains, and so conjures, its own opposite – you might define it as a very delicate way of phrasing transgression… It’s bound up with the archetype of the wife (and maid) as pretty, polite and self-abnegating – a vessel for others’ comfort. But the novel also mentions witches – femininity’s monstrous sister. What do you think the character of Vitória does to these cultural stereotypes?

That it conjures its own opposite was part of what made it the right title in my mind. I also like that it’s a word not spoken very often these days, that it too has a footing in the past. Vitória pushes against the societal limits that have been placed on her through slight transgressions and indecencies in order to find her freedom, to be who she was meant to be. She doesn’t want to be a witch, necessarily, but she sees in the witch a certain sense of liberty to which she relates and wants to get close. In “indelicate” ways, she wants to upend what she sees as the status quo of the rich. She wants to be a little monstrous within it.

“Still in the process of becoming, the soul makes room.” This is the book’s pendulous final line. It’s a beautiful phrase, which empties out the ending’s sense of finality: instead of fixedness, possibility. We do not know what will become of Vitória or her writing. How important to you was this sense of ongoingness at the book’s close?

There’s this notion that a protagonist should undergo a change or transformation by the end of a novel. I’m interested in change and transformation, but I don’t think it ever ends, and I wanted Indelicacy to reflect that. I am also interested in the flawed self and in blind spots, and I wanted the novel to reflect them too. I find it beautiful that there might be room in becoming who we are, always, and in how we change, which is much better than hardening into a self we will never be able to escape.

It also reminded me of a roominess you note earlier on, when Vitória describes how she is “always fooled by these suggestions of other rooms we might go into, but never can, never will”. That felt like an apt metaphor for the dark parts of her character, and the way that teasing glances towards violence never come into full view. The comment at the beginning: “Sitting at my desk, I feel loving towards my wrists. I’ve made them do too much.” Or a bit later: “In a way no one would have predicted, I began to consume my husband, but it would be a long time before either of us understood that.” How did you create Vitória? Which parts of her character came first?

Her voice came first, and as I followed it I found her desires and preoccupations and also her irritations and anxieties, those parts of her drawn to heightened states, and the dark parts of her too. It was important to me to include the warm aspects of her personality, as well as the cold. The loving parts of her, as well as the indecent, and the bits of violence rooted in her, and also in the society of which she is a part. And then there is my eternal fascination with suggestion, with how you can reveal glimpses of a character without overdetermining them, and in how a reader might come to know a character outside of the conscious mind.

I was interested to see that you are finishing work on another book, tentatively titled A Horse at Night. Could you speak a little about that?

A Horse at Night is a meditation on the space of reading and writing fiction, and also of thinking and living. At times it meditates too on other forms, such as visual art and film and video, and in all of these ways is related to Indelicacy, but it’s nonfiction, and the living I reflect on is my own. It’s probably nothing like Orhan Pamuk’s The Naïve and the Sentimental Novelist, which is my favourite book on writing, but it was certainly one inspiration.

Finally, it’s just been announced that Indelicacy has made the shortlist of the Rathbones Portfolio Prize. You must be very pleased.

It came as a complete surprise, and I am incredibly pleased. It means a lot to me to be read, and seen, and I’m so grateful to be read in the UK, and for Indelicacy to have been received so warmly.

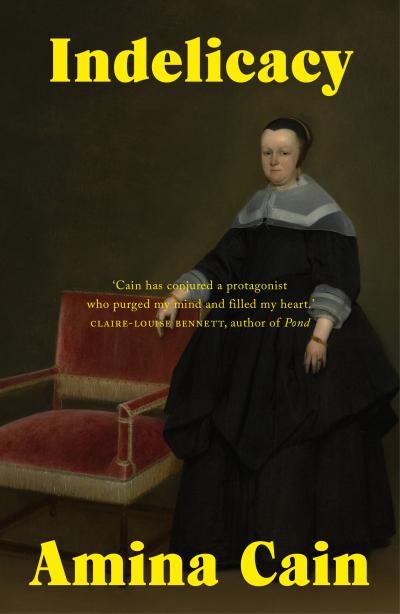

- Indelicacy by Amina Cain (Daunt Books Publishing, £9.99)

- More interviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment