"From today painting is dead" was the pessimistic outcry of Paul Delaroche on first seeing a photograph. Ever since its inception, photography has had a vexed but fruitful relationship with painting. Delaroche specialised in hyper-real historical scenes so he was right to be alarmed, and one could argue that photography's ability to record things in fine detail encouraged painters to seek new forms of expression, including abstraction. Photographers soon followed suit, though, and so the chase continued.

Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art sets out to show how photography and abstract art have a shared history. Juxtaposing photographs from across the world with paintings that supposedly explore similar themes, the exhibition takes you on a whistle stop tour of the 20th and 21st centuries. If the goal is to emphasise the importance of photography as a fine art and reveal the influence it has had on painters and sculptors, it fails.

We still tend to value paintings more highly than photographs, so if you hang one beside another the likely assumption is that the photograph emulates the painting. This idea is reinforced in the first room where Swinging, 1925, an abstract painting by Wassily Kandinsky, is juxtaposed with Homage to Kandinsky, 1937, by Marta Hoepffner (pictured right); she emulates Kandinsky's subtle geometry by placing stencils on photographic paper and exposing them to light.

We still tend to value paintings more highly than photographs, so if you hang one beside another the likely assumption is that the photograph emulates the painting. This idea is reinforced in the first room where Swinging, 1925, an abstract painting by Wassily Kandinsky, is juxtaposed with Homage to Kandinsky, 1937, by Marta Hoepffner (pictured right); she emulates Kandinsky's subtle geometry by placing stencils on photographic paper and exposing them to light.

This example of direct influence sets the tone for the whole show, encouraging one to see all the subsequent photos as monochrome equivalents of paintings. The actual story is far richer and more interesting, though. Had they juxtaposed one of Kasimir Malevich's Suprematist compositions with the aerial shots of landscape that inspired them, it would have revealed a two-way exchange of ideas. They could have quoted another avant guarde Russian artist, Alexander Rodchenko who wrote that “in order to educate man ... everyday familiar objects must be shown with totally unexpected perspectives and in unexpected situations.” The dynamism of his photographs comes from the unusual viewpoints he used to change our perceptions of the world.

On show are four of his photographs, including a superb shot from 1929 of the metal struts of a radio tower spiralling up towards infinity. They should have dedicated a whole room to him, to show how photography, photomontage and collage were an integral part of his output as a painter and designer. Photography was not, he insisted, an adjunct to fine art, but “has every right and every merit to claim our attention as the art of our age.”

The Hungarian artist, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy is given more space, but is represented only by photographs and a painting, which is to miss the whole point of his work and that of other mutimedia artists from the 1920s onwards. He and Rodchenko challenged the supremacy of painting by refusing to see any medium as more important than another and by working in fields as diverse as film, graphic and theatre design, sculpture, painting and light shows.

The Hungarian artist, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy is given more space, but is represented only by photographs and a painting, which is to miss the whole point of his work and that of other mutimedia artists from the 1920s onwards. He and Rodchenko challenged the supremacy of painting by refusing to see any medium as more important than another and by working in fields as diverse as film, graphic and theatre design, sculpture, painting and light shows.

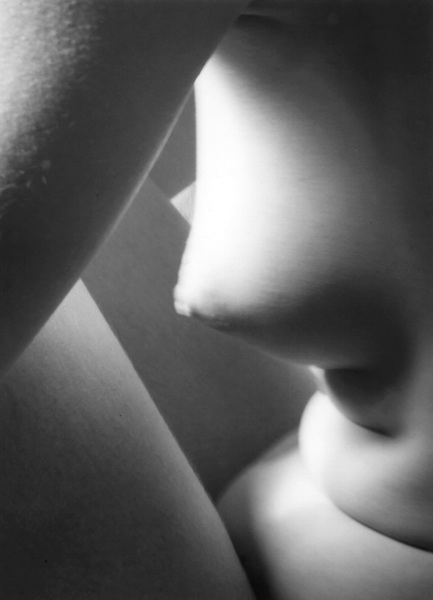

In any case, it would have been better to select one photographer to represent each tendency or trend and show their work in depth, rather than include numerous artists with one or two pictures each. The labelling is so poor that it is virtually impossible to figure out who took which photographs. The only thing one learns from the rows and banks of images (pictured below: installation shot by Seraphina Neville) is that, at any one time, a lot of people in different parts of the world were taking similar shots – whether of carpet threads and vinyl grooves, stacks of wood, paper or pipes, distorted and abstracted nudes (pictured above left: Triangles 1928, by Imogen Cunningham), crumbling walls and peeling paintwork or patterns of light and dark, both found and created.

On the other hand, I was delighted to be introduced to the work of Bela Kolarova, a Czech photographer I’d never heard of who, in the 1960s and ‘70s, made photograms with shells and bottle tops and whose wizardry with stencils in the dark room led to exquisitely subtle arrangements of lines, textures and repeating patterns.

Nor did I know that American painter, Ellsworth Kelly took photographs that replicate the spatial ambiguities he explores in his shaped canvases. On show are photographs from the 1970s of a road marking resembling a shaft of divine light, a cinema screen tilted to become a rhomboid and a tree casting its shadow across the pavement and nearby wall. These wonderful examples of life copying art are lost on one, though, without one of Kelly's paintings for comparison.

Nor did I know that American painter, Ellsworth Kelly took photographs that replicate the spatial ambiguities he explores in his shaped canvases. On show are photographs from the 1970s of a road marking resembling a shaft of divine light, a cinema screen tilted to become a rhomboid and a tree casting its shadow across the pavement and nearby wall. These wonderful examples of life copying art are lost on one, though, without one of Kelly's paintings for comparison.

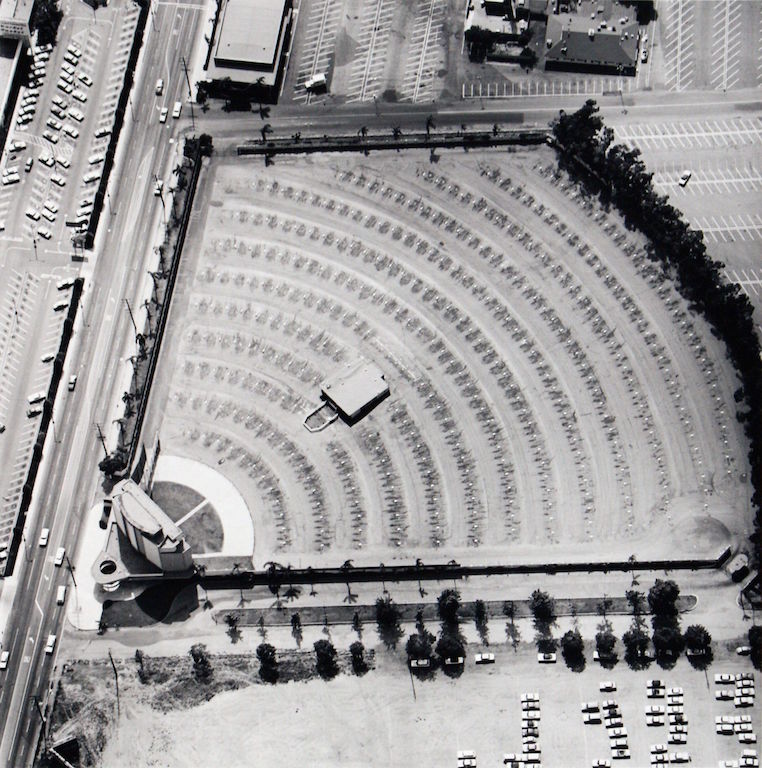

Ed Ruscha obsessively catalogues the world around him in photographs of palm trees, gas stations and the empty parking lots on show; seen from above, the herring bone patterns that mark the different bays create delicate traceries across the tarmac (pictured above right: Gilmore Drive-in Theater - 6201 W. Third St.1967). They are coupled with a Carl Andre floor sculpture, a link that makes little sense except that both form grids. Why not show one of Ruscha's pared-down paintings of buildings and signs, or establish an intelligent dialogue between photography and sculpture by including sculptors like Richard Long and Hamish Fulton in whose work photography plays a vital role? They were part of an explosion of multimedia work that erupted in the 1970s and continues to flourish to such an extent that many art schools have abanonded traditional categories in favour of multimedia departments. But there's scarcely a whiff of this interplay in the show, which still encourages one to think of photography, painting and sculpture as separate disciplines.  Even on its own terms the exhibition doesn't work. Many wonderful pictures are included, but by bundling them together under arbitrary titles such as Finding Form, Drawing with Light (main picture: Luminogram II, 1952, by Otto Steinert) and Subjectivity and Expression, the show reduces the work to a common denominator and, thereby, robs it of context, meaning and poetry while offering precious little illumination concerning the fruitful dialogue between abstract painting and photography that has lasted a hundred years and is set to continue.

Even on its own terms the exhibition doesn't work. Many wonderful pictures are included, but by bundling them together under arbitrary titles such as Finding Form, Drawing with Light (main picture: Luminogram II, 1952, by Otto Steinert) and Subjectivity and Expression, the show reduces the work to a common denominator and, thereby, robs it of context, meaning and poetry while offering precious little illumination concerning the fruitful dialogue between abstract painting and photography that has lasted a hundred years and is set to continue.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment