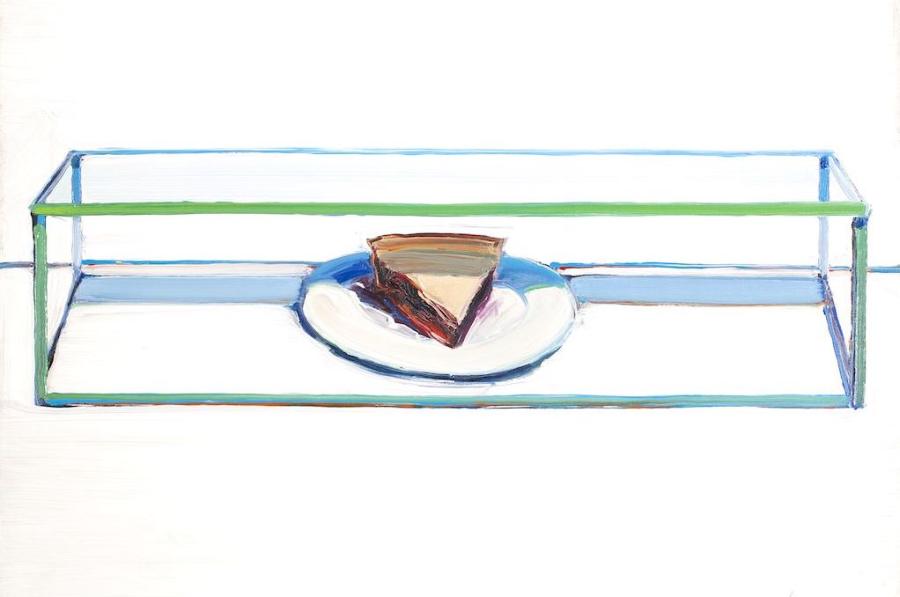

A lone slice of cherry pie sits on a plate inside a glass case (pictured below), waiting to be released from its solitary confinement and guzzled by a hungry diner. There it is again, in an eye-watering display of sickly offerings (main picture). This time, four slices are lined up alongside their chocolate, pecan and lemon meringue counterparts. The display goes on and on, for as far as the eye can see.

At first glance, Wayne Thiebaud’s pictures of cakes, pies, hot dogs, ice creams and gob stoppers look like euphoric celebrations of abundance; but gazing at this glut of comfort food soon makes you feel uncomfortable – even downright queasy More is not always better. A record of the goodies on offer at any food counter across the U.S.A, his paintings of quintessential American treats were often shown, in the 1960s, alongside Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein; yet Thiebaud was never really a Pop artist.

He’d worked as an illustrator and commercial artist and spent time in Walt Disney’s animation department, yet when he switched to fine art it was to painters like Chardin, Manet and Monet that he looked for inspiration. He saw himself as part of the grand tradition of still life painting, which has always been about more than portraying objects on tables. He also went to New York where he met Elaine and Wilhelm de Kooning and was bowled over by their free-hand gestural expression.

The Courtauld exhibition is the first time his pictures have been shown in the UK and, boy, are they delicious – not because the edibles they portray are desirable, but because the paintings are finger licking good. They’re a seduction, an offering, but they are also much, much more.

I don’t have a sweet tooth, so I’ve often gazed at the confections on display in cake shops windows and wondered if any are edible and what they’d do to the teeth and liver of anyone foolish enough to eat them. We know now, of course, that processed and sugary foods poison your system but, in the 1960s, delights like cakes, frankfurters, hot dogs and bubble gum were perceived as innocent pleasures.

Yet with his exaggerated colours (the sinister blue shadows are particularly chilling), Thiebaud seems to anticipate this realisation. Then there’s the brush work. He lathers on the paint with such panache that the swipes, slabs and dollops of pigment are as present as the foodstuffs they portray. His slices of pie may look as inert as polystyrene models, but the gaps between the plates are alive with vigorous brush marks. Some pies have icing sugar toppings made with lashings of creamy white paint: “white, gooey, shiny, sticky oil paint spread out on the top of a painted cake becomes frosting”, Thiebaud explained; “it is playing with reality.” You can almost hear him licking his lips with glee as he plays visual games with the viewer in pictures that celebrate paint as both stuff and illusion.

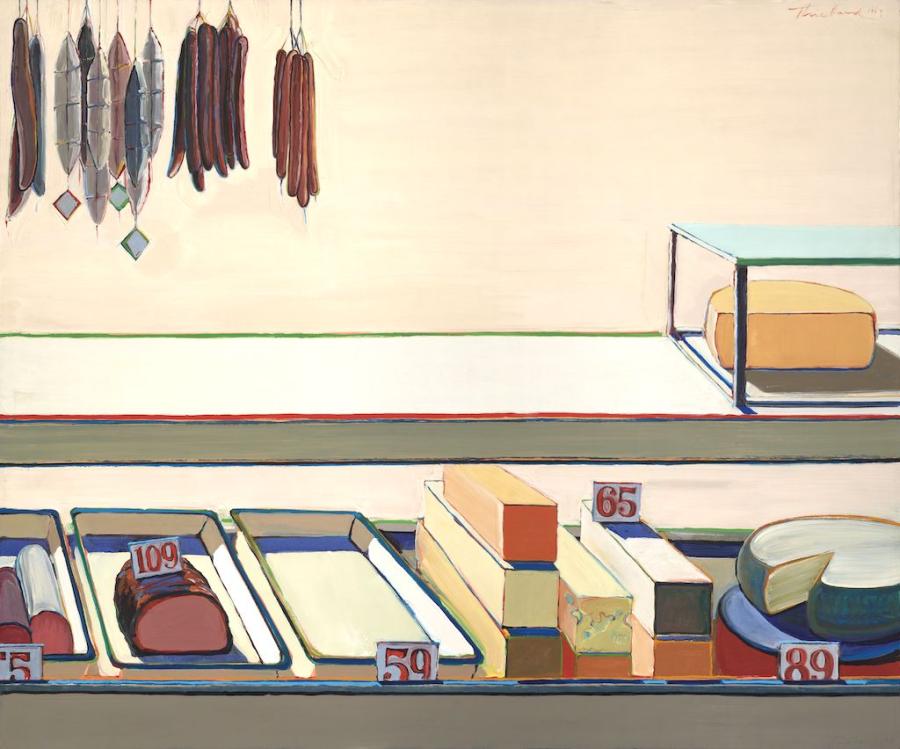

In his pictures, the spaces between things are mini abstracts. The cheeses stacked in the display case of Delicatessen Counter 1963 (pictured above) look less inviting than the empty tray beside them, and the table top on which a loan mug stands in Coffee Cup 1961 (pictured below right) is articulated with the same gusto as one of Robert Ryman’s abstract riffs on whiteness.

But Thiebaud manages to have his cake and eat it. His love of abstraction shines through, yet the objects he paints are so evocative that they grab your attention and even suggest stories. Mugs like the one in Coffee Cup, for instance, were a feature of the diners proliferating across America at the time and, for me, this loan cup triggers a filmic scenario. It’s cold blue shadow evokes the harsh fluorescent lighting of a sterile interior, while the scummy coffee looks as if it has long since gone cold. I imagine a solitary soul whiling away the dreary hours, just like the lonely night owls that inhabit an Edward Hopper painting.

For, despite their veneer of cheeriness, there’s something forlorn about the things Thiebaud chooses to paint. The cakes proliferating across the canvas like gaudy hats, the bubble gum crammed into glass domes and the lollypops jostling for attention suggest that plenitude is no guarantee of satisfaction. Nourishment is what’s needed, but fast food is moreish exactly because it has little food value. In which case, a row of hot dogs (pictured below) is a perfect metaphor for the American dream, a state of wellbeing that remains elusive no matter how hard you chase it.

Thiebaud’s ice cream cones readily fit into the tradition of the still life as a memento mori – a reminder that pleasure is fleeting and life is short. And his paintings often suggest that while consumerism may briefly satisfy one’s cravings, it can never fulfil one’s deeper desires and longings. None of this may have been in his mind, of course, although he referred to his pictures as staged performances and his chosen objects as like “characters in a play with costumes”.

Downstairs in the Drawings Gallery there’s an exhibition of his etchings, drawings and woodcuts, which are an absolute delight. Most are in black and white and, without the exaggerated palette of the paintings, the mood is totally different. The slices of cake look yummy and the ice creams cones seem comic yet heroic. Later Thiebaud hand-coloured some of the etchings in subtle hues that suggest enormous affection and nostalgia for the goodies with which he chose to represent America.

And it’s this ambiguity that makes the pictures so memorable. Because you can never get to the bottom of them, the love affair continues – endlessly.

- Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life is at the Courtauld Gallery until 18 January 2026

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

- All embedded pictures are © Wayne Thiebaud/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2025

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment