Frank Stella: Connections, Haunch of Venison | reviews, news & interviews

Frank Stella: Connections, Haunch of Venison

Frank Stella: Connections, Haunch of Venison

Stella paints beautiful answers to intriguing questions - only where's the heart?

Art about art is one of my favourite kinds of art. Paintings, drawings, sculptures, films - works of art which talk about what art is, what the image is, what art can represent and what it can't - all appeal. It is not just a picture of some prostitutes and some African masks - it is Les demoiselles d'Avignon by Picasso and it blows apart the boundaries of painting by cramming three dimensions into two.

I know that Stella is someone contemporary art critics should love - he methodically and beautifully asks those key questions about art, he is (by his own assessment, not much demurred from) one of the greatest abstract painters of his generation. There is nothing wrong with this retrospective by any means: two rooms are taken up almost solely by the sketches, designs, maquettes and realisations of two works of art, a detailed and enlightening curation showing the thought process and method of manufacture, and how the idea develops. And yet, and yet...

The first painting is in many ways the most stimulating: Delta (1958) (pictured left) is a series of chevrons whose ends extend up or down, all painted in black. Inspired by Jasper Johns's stripy works, Stella decided to work in the same way, except in anger he turned to black. Suddenly an exploration of colour fields turned into an investigation of depth. The chevrons alternate between glistening, sweating blacks which ask the viewer whether it is possible to distinguish different planes, foreground from background - the form of a traditional picture. (By this point in Abstract Expressionism, representation of an object is no longer an issue, Rothko, Newman et al having done away with that.) This is the question he would go on to answer, in varying ways, ever since.

The first painting is in many ways the most stimulating: Delta (1958) (pictured left) is a series of chevrons whose ends extend up or down, all painted in black. Inspired by Jasper Johns's stripy works, Stella decided to work in the same way, except in anger he turned to black. Suddenly an exploration of colour fields turned into an investigation of depth. The chevrons alternate between glistening, sweating blacks which ask the viewer whether it is possible to distinguish different planes, foreground from background - the form of a traditional picture. (By this point in Abstract Expressionism, representation of an object is no longer an issue, Rothko, Newman et al having done away with that.) This is the question he would go on to answer, in varying ways, ever since.

One of his responses was that instead of some false illusionistic manner of creating depth - painting the far-off man smaller - you had to give the canvas actual depth, make some layers sit further forward, some backward. Felstzyn III (1971) is on an adjacent wall, with its further-back green plane.

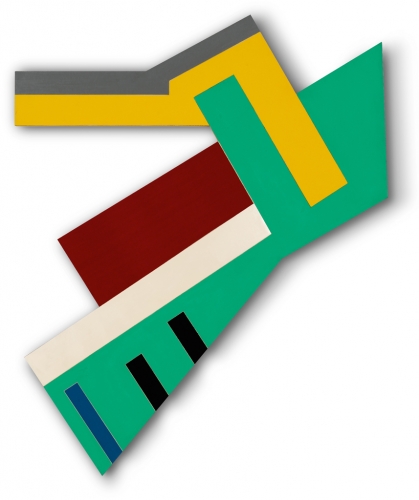

This line of argument is shown most eloquently in the next room, with three versions of Suchowola (1973) (pictured right), where we start with a flat, if highly irregular, shape (his Irregular Polygons play the same game with the form of the picture), then have the same shape but with colours sitting on different levels, and finally Stella tilts some of the planes forward, so they sit at angles to others. This is a revelation, putting three dimensions into actual painting (as opposed to Cubism's painted third dimension or Rauschenberg's real objects on canvases). This show does not hide Stella's struggle with space, and the results are thrilling to the eye and the mind: odd colours, odd shapes, odd angles striving to break out of art as we knew it.

This line of argument is shown most eloquently in the next room, with three versions of Suchowola (1973) (pictured right), where we start with a flat, if highly irregular, shape (his Irregular Polygons play the same game with the form of the picture), then have the same shape but with colours sitting on different levels, and finally Stella tilts some of the planes forward, so they sit at angles to others. This is a revelation, putting three dimensions into actual painting (as opposed to Cubism's painted third dimension or Rauschenberg's real objects on canvases). This show does not hide Stella's struggle with space, and the results are thrilling to the eye and the mind: odd colours, odd shapes, odd angles striving to break out of art as we knew it.

A complete dive into three dimensions is in the next room, where La penna di hu (1983-87) takes shape. Stella uses cones, tubes, even something which looks like a Soviet sickle to make a sculpture, no longer a painting. It is dynamic and witty and prettily coloured in all its variations. These pieces might seem like nothing new - sculptors have been working in 3D forever - but because they developed from his work in painting, they reflect a new approach to sculpture. There are still paintings and drawings of La penna di hu which have almost a perverse desire to show that, having captured painting in sculpture, sculpture can be captured in painting. (His later move into stand-alone sculpture followed naturally.)

The questions Stella is asking are academic, of great moment to artists but probably not to others

All of these pieces made my mind hum. Stella's most famous paintings, the bright stripes and squares (such as Les Indes galantes above), did not. I looked at all the examples Haunch offered and not one stirred me - where had Stella's ability to ask fascinating questions gone? The endless combinations of schoolkid colours are repetitive - hypnotic and appealing to the eye, perhaps, but deeply repetitive. Instead of wondering how he can squash reality onto a canvas, he seems to be dancing about like a maiden round a maypole.

While I was being disabused by these works, a thundering realisation struck me. Where was the human in all of this? And, looking back to the start, where was the human in any of this? The questions Stella is asking are academic, of great moment to artists but probably not to others. I am as interested in shapes and planes as the next man, but these are cool works, not stimulated or impassioned. What, ultimately, do these works mean to us? This is not a plea for sentiment in art, but some of the greatest art about art - such as the Demoiselles - still manages to be cheeky, or erotic, or desperate, or loving, or grievous, or pitiable, or monstrous, or in some manner moving. Stella, I'm sorry to say, is not.

- Frank Stella: Connections at Haunch of Venison until 19 November

Explore topics

Share this article

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Brancusi, Pompidou Centre, Paris review - founding father of modernist sculpture

Uplifting quest for form and essence in a landmark Paris show

Brancusi, Pompidou Centre, Paris review - founding father of modernist sculpture

Uplifting quest for form and essence in a landmark Paris show

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity

Wonderful paintings, but only half the story

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity

Wonderful paintings, but only half the story

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Add comment