Curiosity: Art & the Pleasures of Knowing, Turner Contemporary | reviews, news & interviews

Curiosity: Art & the Pleasures of Knowing, Turner Contemporary

Curiosity: Art & the Pleasures of Knowing, Turner Contemporary

Curiouser and curiouser: what do Venice and Margate have in common (beside the seaside)?

One of this summer’s seaside attractions in Margate is an overstuffed walrus, but day-trippers won’t find it in the town’s Museum of Monstrosities. The taxidermic freak, on loan from the Horniman Museum, is the star exhibit in the new show at Turner Contemporary. Against the backdrop of a North Sea painted by Turner, the adipose Arctic mammal is out of its element.

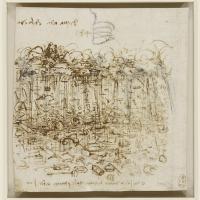

Curated by Brian Dillon, UK editor of Cabinet magazine, this is certainly a curious exhibition: an informatively captioned anthology of intriguing objects - ancient and modern, natural and man-made, real and fictitious - that refuse to fit neatly into the categories of art or science. It features five sheets of doodles by Leonardo and that famous woodcut of a rhinoceros by Dürer (also zoologically incorrect) alongside works by contemporary artists such as Gerard Byrne, Tacita Dean and Jimmie Durham. It opens with John Evelyn’s empty curiosity cabinet (pictured below) and closes with the Horniman’s Walrus, taking in a diverse range of oddities, animal, vegetable and mineral, in between.

In recent years we’ve got used to museums’ attempts to make science sexy by allying it with art through residencies and commissions, but Dillon insists that his show is “not about art and science.” Its subject is the psychological driving force behind both: the human quality variously described by Lord Byron as a “low vice”, Samuel Johnson as the “thirst of the soul”, Bernard of Clairvaux as the “beginning of all sin and John Locke as the “great instrument nature has provided to remove that ignorance [children] were born with”.

In recent years we’ve got used to museums’ attempts to make science sexy by allying it with art through residencies and commissions, but Dillon insists that his show is “not about art and science.” Its subject is the psychological driving force behind both: the human quality variously described by Lord Byron as a “low vice”, Samuel Johnson as the “thirst of the soul”, Bernard of Clairvaux as the “beginning of all sin and John Locke as the “great instrument nature has provided to remove that ignorance [children] were born with”.

In the age of the internet search engine, curiosity has gone viral and the art world seems to have caught the bug. Last year the Botanique in Brussels staged a contemporary art exhibition titled Wunderkammer; this year the Venice Biennale’s international art exhibition has taken its name from the Baroque wunderkammer’s Enlightenment successor, the encyclopaedia.

The Encyclopedic Palace is a homage by young Italian curator Massimiliano Gioni to the self-taught Italian-American artist Marino Auriti, who developed a fantastic plan for a Babel-shaped tower containing all human knowledge and filed his design with the US Patent Office in 1955. Like Thomas Browne’s imaginary Musaeum Clausum, Auriti’s dream palace necessarily remained a dream. But that, for Gioni, was part of the point. He found an analogy between Auriti’s unrealisable ambition and the global model of the modern art biennale, with its “impossible desire to concentrate the infinite worlds of contemporary art in a single place; a task that now seems as dizzyingly absurd as Auriti’s dream”. He also saw “interesting parallels between the ‘wunderkammer’ and today’s culture of hyper-connectivity”.

Although his show takes its name from an encyclopaedia, its structure is closer to the organised chaos of the cabinet of curiosities on which the Enlightenment, with its obsession for classification, imposed encyclopaedic order. Like Dillon’s Margate show, Gioni’s Venice exhibition includes work by non-artists. It opens with Carl Jung’s Red Book and features Aleister Crowley’s Tarot cards and Rudolf Steiner’s blackboard drawings. There is even an overlap between the two shows, whose curators only discovered each other’s plans when competing to borrow stones with surreal patterns from the collection of Roger Caillois (pictured above left, Agate, Petit poisson, Mineralogy, Caillois Collection, © MNHN). (Venice got the lion’ share.)

Although his show takes its name from an encyclopaedia, its structure is closer to the organised chaos of the cabinet of curiosities on which the Enlightenment, with its obsession for classification, imposed encyclopaedic order. Like Dillon’s Margate show, Gioni’s Venice exhibition includes work by non-artists. It opens with Carl Jung’s Red Book and features Aleister Crowley’s Tarot cards and Rudolf Steiner’s blackboard drawings. There is even an overlap between the two shows, whose curators only discovered each other’s plans when competing to borrow stones with surreal patterns from the collection of Roger Caillois (pictured above left, Agate, Petit poisson, Mineralogy, Caillois Collection, © MNHN). (Venice got the lion’ share.)

Something distinctly curious seems to be happening. Is the 17th-century wunderkammer staging a comeback as a 21st-century mode of display for the sampling era? Or is a new generation of contemporary art curators rephrasing the old left-brain, right-brain, science v art debate for the conceptual age? In the days when art was regarded as primarily visual, artists were expected to teach us new ways of seeing; now that art is supposedly conceptual, they’re apparently expected teach us new ways of thinking. The Biennale’s president Paolo Baratta described The Encyclopedic Palace as “an exhibition of research” into what makes an artist, and suggested that – under the current deluge of mass media imagery – the world needs artists to “pass through them unharmed, as Moses did in the Red Sea”.

Artists have always taken inspiration from untidy personal collections of objects and images stored in their studios as creative cabinets of curiosity. Baratta’s Red Sea simile may be a ford too far, but is there any sense in his suggestion that artistic thinking can help us cope with information overload? The right-brain approach to the British Museum collections adopted by Grayson Perry in his 2011 exhibition The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman was undeniably popular with the public. But that was letting an artist loose in a museum; Curiosity is letting museum objects loose in an art gallery, where left-brainers would argue they don’t belong. Is the experience of viewing a stuffed walrus at Turner Contemporary qualitatively different from viewing a stuffed Guy the Gorilla in the new Cadogan Gallery of selected treasures from the Natural History Museum? Both displays also happen to feature models of marine invertebrates by the German glassmakers Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka (pictured above right, Rudolph and Leopold Blaschka, Argonauta argo, c.1860-90, © Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru, National Museum of Wales).

Artists have always taken inspiration from untidy personal collections of objects and images stored in their studios as creative cabinets of curiosity. Baratta’s Red Sea simile may be a ford too far, but is there any sense in his suggestion that artistic thinking can help us cope with information overload? The right-brain approach to the British Museum collections adopted by Grayson Perry in his 2011 exhibition The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman was undeniably popular with the public. But that was letting an artist loose in a museum; Curiosity is letting museum objects loose in an art gallery, where left-brainers would argue they don’t belong. Is the experience of viewing a stuffed walrus at Turner Contemporary qualitatively different from viewing a stuffed Guy the Gorilla in the new Cadogan Gallery of selected treasures from the Natural History Museum? Both displays also happen to feature models of marine invertebrates by the German glassmakers Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka (pictured above right, Rudolph and Leopold Blaschka, Argonauta argo, c.1860-90, © Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru, National Museum of Wales).

These exquisite creations could help settle the question. Despite their intricate beauty, they were made as teaching aids by artisans who refused to call themselves artists – and yet, argues Dillon, their “sense of strangeness is as much part of science as art”. It may be time to relax the Enlightenment definitions and go with the dilettanteish flow of the Baroque collector. Our obsession with classifying what is and what is not art has helped to create a situation in which expert classification of an object as art is considered necessary to engage an audience’s interest. But an audience’s interest is freely given when its curiosity is pricked, as the Wellcome Collection has repeatedly proved with its category-defying exhibitions such as Death: A Self-Portrait, which juxtaposed human remains with Renaissance vanitas paintings.

“I don’t think the question of whether they are art or not is very interesting,” Dillon says of the objects in his exhibition. The pleasures of knowing and seeing are too often separated in contemporary exhibitions. Any show that reunites them must be worth a visit, whether in an art gallery or a museum.

- Curiosity: Art & the Pleasures of Knowing at Turner Contemporary, Margate until 15 September and at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery from 28 September to 5 January 2014

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment