Undines, mermaids, selkies, nixies, kraken. You’ll encounter such imaginary creatures in Aquatopia, an exhibition which delves into the myths of the ocean deep, and thereby to the murky, fathomless depths of our subconscious. But more often than imaginary beings you’ll encounter real ones who’ve touched our imaginations by their unearthly appearance and tapped into our deepest fears and desires, which means, naturally, our sexual desires. There’s a lot of octopus love going on.

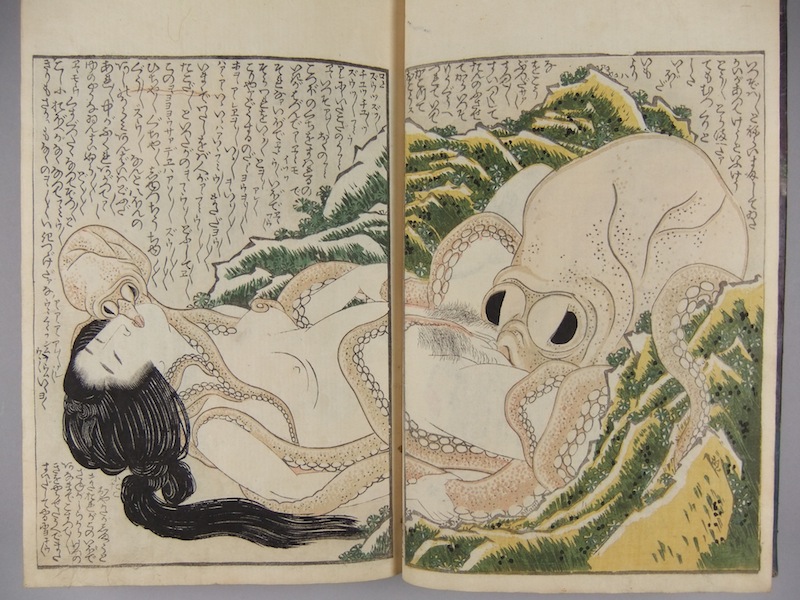

Katsushika Hokusai’s famous erotic print of 1814, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (pictured below), shows a woman being pleasured by octopus, one at each end, to the mutual satisfaction of all parties, and we find Turner Prize-nominee Spartacus Chetwynd’s contemporary response to it: a filmed performance of her sexual congress with a giant octopus. Resembling a grounded hot-air balloon, Chetwynd’s latex and papier-mâché octopus lies spent and inert nearby.

We also encounter an octopus lying in the middle of a hotel bed in Rome, perhaps awaiting its human mistress and the chance to get its clammy suckers on her, while, in another photograph by Juergen Teller, squid-ink spaghetti spills out of Björk’s mouth (main picture) like a jet of black blood, or indeed semen – take your pick, since Eros and Thanatos are close Freudian bedfellows. Next to those, we find a marvellous painting by Lucian Freud (pictured below right) of a squid leaking its ink near a spiky sea urchin, a sinister coupling if there ever was one.

We also encounter an octopus lying in the middle of a hotel bed in Rome, perhaps awaiting its human mistress and the chance to get its clammy suckers on her, while, in another photograph by Juergen Teller, squid-ink spaghetti spills out of Björk’s mouth (main picture) like a jet of black blood, or indeed semen – take your pick, since Eros and Thanatos are close Freudian bedfellows. Next to those, we find a marvellous painting by Lucian Freud (pictured below right) of a squid leaking its ink near a spiky sea urchin, a sinister coupling if there ever was one.

This is an exhibition which has thrown its net wide to trawl for the old and the new, and for the art and the non-art object, alike. It’s a thoroughly engaging underwater cabinet of curiosities, just the type of exhibition which has become terribly fashionable in recent years. You can, for instance, currently pop down to Margate to catch Curiosity and encounter a dusty stuffed walrus. But the fact that Nottingham is nowhere near the sea makes this themed summer sojourn somehow more irresistible – indeed, more serious and alert to its unsettling themes. Even with its exhibition spaces bathed in a blue, watery light it feels less like a deliberate crowd-pleaser than it might, although it will be moving, with additional work, to Tate St Ives in October.

This is an exhibition which has thrown its net wide to trawl for the old and the new, and for the art and the non-art object, alike. It’s a thoroughly engaging underwater cabinet of curiosities, just the type of exhibition which has become terribly fashionable in recent years. You can, for instance, currently pop down to Margate to catch Curiosity and encounter a dusty stuffed walrus. But the fact that Nottingham is nowhere near the sea makes this themed summer sojourn somehow more irresistible – indeed, more serious and alert to its unsettling themes. Even with its exhibition spaces bathed in a blue, watery light it feels less like a deliberate crowd-pleaser than it might, although it will be moving, with additional work, to Tate St Ives in October.

The exhibition naturally takes its cue from literature, since it’s literature that’s bought these sea-bound myths down to us, as well as given us new ones. There’s Gustave Doré’s utterly entrancing series of prints (1797-78) illustrating Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner; there’s Karl Weschke’s painting of a prone Caliban, (1977-78) thrown against a desolate landscape; there’s Herbert James Draper’s 1895 painting A Water Baby, illustrating Charles Kingsley’s popular Victorian children’s story, The Water Babies; Gen Ben-Ner’s thoroughly amusing restaging of Moby Dick filmed in his kitchen; and Bernard Buffet’s huge painting illustrating a scene from Jules Verne’s Twenty-thousand Leagues under the Sea.

Works that stand entirely in a league of their own, however, are few, though they do include Turner’s Sunrise with Sea Monsters, and two brilliant paintings by his almost forgotten contemporary Francis Danby: The Deluge (pictured below) and The Shipwreck both depict terrifying apocalyptic scenes, though in themselves have little to do with mythical underwater worlds. And nowhere will you find an example of craftsmanship as delicate and exquisite as Rudolf and Leopold Blaschka’s 19th-century blown-glass jellyfish.

Meanwhile, a new legend meets with the old in The Otolith Group’s film Hydra Decapita, inspired by Nineties Detroit-based techno duo Drexciya. The duo invented a story of amphibious descendants of African slaves, the imagined offspring of the pregnant slaves routinely thrown overboard during transportation and who go on to found a fabled society called Drexciya (which, incidentally, has also inspired the work of American artist Ellen Gallagher, though none of Gallagher’s work could be obtained for this exhibition). It’s a somewhat obtuse film, made even more so by the fact that it was difficult to watch in its entirety, the Guardian’s art critic having extended his full length on the one communal seat available to view it, and not budging for anyone. But, with over 150 works, this is a sprawling exhibition, so you’re practically swimming in a sea of stuff.

Meanwhile, a new legend meets with the old in The Otolith Group’s film Hydra Decapita, inspired by Nineties Detroit-based techno duo Drexciya. The duo invented a story of amphibious descendants of African slaves, the imagined offspring of the pregnant slaves routinely thrown overboard during transportation and who go on to found a fabled society called Drexciya (which, incidentally, has also inspired the work of American artist Ellen Gallagher, though none of Gallagher’s work could be obtained for this exhibition). It’s a somewhat obtuse film, made even more so by the fact that it was difficult to watch in its entirety, the Guardian’s art critic having extended his full length on the one communal seat available to view it, and not budging for anyone. But, with over 150 works, this is a sprawling exhibition, so you’re practically swimming in a sea of stuff.

- Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep at Nottingham Contemporary until 22 September, then at Tate St Ives in October

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment