Allen Jones, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Allen Jones, Royal Academy

Allen Jones, Royal Academy

A brilliant painter derailed by an unfortunate obsession

There’s no escaping it; Hat Stand, 1969, is a beastly object. The blank-faced mannequin is too literal to succeed as a sculpture, and the conceit is too nasty to be ignored. Her position – holding up her hands to receive our hats – recalls the torture meted out to prisoners of war by their Japanese guards in WWII.

Over the years her more famous sisters, Chair and Table, have attracted considerable hostility. "Chair" lies on her back, legs in the air; the seat is strapped to her thighs so that her calves act as the chair back. "Table" kneels on all fours with a sheet of glass bolted to her back. Both are dressed in fetish gear and are in positions implying sexual availability. They are still as irritatingly silly and sexist as they were nearly 50 years ago.

But Allen Jones’s retrospective contains another Table, which is far more interesting because it is more ambiguous. Rather than flesh pink, the fibreglass is painted a dark, sparkly green, the glass is shaped like an artist’s palette and the woman’s head is lifted. Her unreal colour and more active demeanour are reminiscent of sci-fi and video game heroines; she may be enslaved but she is not cowed. And her implied role – as an artist’s muse and support – is shown to be a trap.

The furore caused by his fetishistic furniture has done Allen Jones no good; it has eclipsed the fact that, as this exhibition reveals, he is a superb draughtsman and subtle painter. My first encounter with one of his paintings, in the early 1960s, shocked me to the core. I was a student at the Slade School of Fine Art when an exhibition was staged of paintings by our counterparts at the Royal College.

While we were churning out dull, academic nudes and high-minded compositions on biblical themes, they were painting striped toothpaste escaping the tube (Derek Boshier), a packet of Typhoo tea (David Hockney) and a fleet of red buses (Allen Jones). While we were pompous, they were real and it showed in the vitality and gusto of their pictures. The Pop Art invasion blew the cobwebs from our musty institution.

While we were churning out dull, academic nudes and high-minded compositions on biblical themes, they were painting striped toothpaste escaping the tube (Derek Boshier), a packet of Typhoo tea (David Hockney) and a fleet of red buses (Allen Jones). While we were pompous, they were real and it showed in the vitality and gusto of their pictures. The Pop Art invasion blew the cobwebs from our musty institution.

Over the next few years, Jones painted a fleet of bus pictures. Instead of the muddy browns and beiges we employed, he used pillar box red, orange and emerald green; alongside painterly gestures he juxtaposed flat areas of colour with hard edges resembling graphic design and wrote over them in capitals the word BUS. The wheels are like targets and visible through the windows are passengers wearing multicoloured stripes and spots, while changes in scale and shifts in perspective make it impossible to differentiate inside from out.

Several are included in the show (pictured above left: Interesting Journey, 1962) and they are as sophisticated and complex as ever. In Sun Plane, 1963, Jones flirts with abstraction. Seen against a fried egg sun, the silhouette of a biplane is traversed by red and green stripes that, like camouflage, break up the shape and flatten the form. Man Woman, 1963, explores what was to become an enduring theme. Fluid strips of bright colour blend into one being; it's a union between male and female and between figuration and abstraction since, being headless, the pair happily occupy the middle ground between portraiture and colour field painting.

Twenty years later, these glorious forays into spatial ambiguity led to semi-figurative sculptures of dancers such as Red Ballerina, 1982. Cut from plywood or sheet steel, they are like Matisse cut-outs that have sprung into dynamic, 3D life. The best ones – of single female figures – are the most abstract; the couples are often spoiled by the addition of faces delineated with cartoonish clarity (pictured right: Fascinating Rythm, 1983).

Twenty years later, these glorious forays into spatial ambiguity led to semi-figurative sculptures of dancers such as Red Ballerina, 1982. Cut from plywood or sheet steel, they are like Matisse cut-outs that have sprung into dynamic, 3D life. The best ones – of single female figures – are the most abstract; the couples are often spoiled by the addition of faces delineated with cartoonish clarity (pictured right: Fascinating Rythm, 1983).

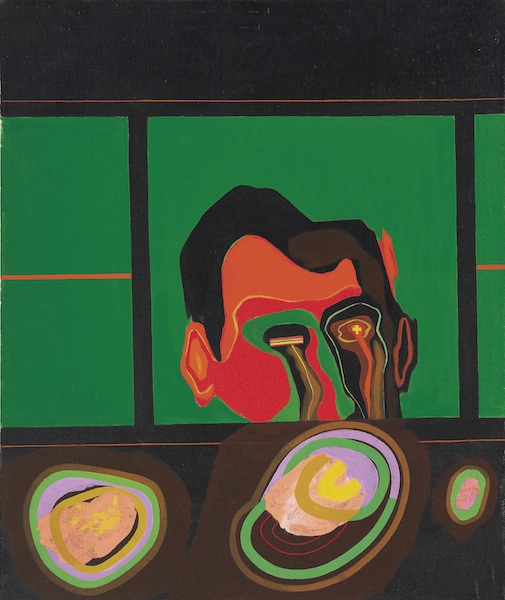

Had Jones continued on this course, I would be celebrating his brilliance without any reservations, but an obsession with scantily clad women introduced a new element. Inspired by the soft porn and girlie mags he discovered in New York in 1964, he began working in a more illustrative style in which erotic charge and dramatic effect takes precedence over painterly nuance.

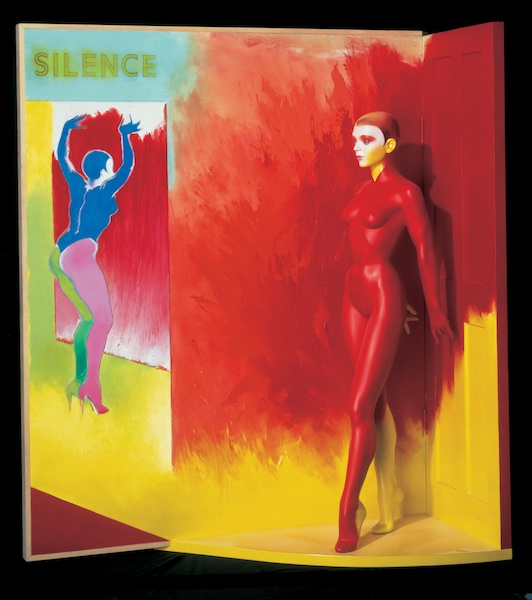

First Step, 1966 is of a pair of legs draped in see-through fabric perched on excessively high heels. The addition of a shelf announces an interest in three-dimensions. Later this led to composite works such as Stand In, 1992 (pictured below), in which a fibreglass figure stands on a shelf ready, as it were, to enter the picture which features a dancer performing on stage. Doubtless intended as a witty exploration of the relationship between painting and sculpture, actual and illusory space, the juxtaposition is too obvious to be interesting.

The equation between painting and performance, in which the canvas is compared to a stage, enabled Jones to focus on acrobats, dancers and magicians. As the focus shifts from the language of painting to the glamour of showbiz, colours become more saccharine and ambiguity gives way to drama.

The equation between painting and performance, in which the canvas is compared to a stage, enabled Jones to focus on acrobats, dancers and magicians. As the focus shifts from the language of painting to the glamour of showbiz, colours become more saccharine and ambiguity gives way to drama.

Caught in the Act, 2001, shows a magician sawing in half a female assistant as she lies supine inside a box. Taken piecemeal, the composition is still an exquisitely subtle exploration of painting’s ability to be either precise or vague, vaporous or hard-edged, illusionistic or flat, abstract or figurative; but this display of mastery is spoiled by showbiz melodrama and the mask-like idiocy of the woman’s face.

And just as the abstracted paintings led to the sculptural cut-outs of the Eighties and Nineties, the performers began in 2000 to appear as fibreglass figures encased in clinging body suits, confining sheaths and even boxes that hark back to the fetishistic furniture. What a shame that an artist blessed with extraordinary graphic skills should squander his talent on such banal embodiments of lust. These zombies have all been shepherded into one room. It would be best to lock the door and throw away the key.

GREAT POP ART RETROSPECTIVES

Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery. An exhibition of still lifes which are anything but still

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

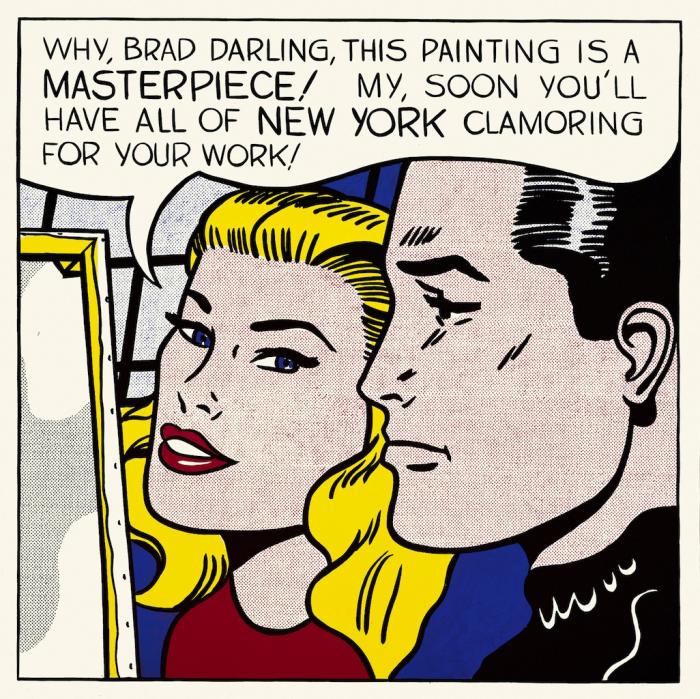

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Tate Modern. The heartbeat of Pop Art is given the art-historical credit as he deserves (pictured above, Lichtenstein's Masterpiece, 1962)

Patrick Caulfield, Tate Britain. A late 20th-century great emerges into the light

Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, Pallant House Gallery. The paintings are wonderful, but the curator does a huge disservice to this forgotten artist

Richard Hamilton, Tate Modern /ICA. At last, the British 'father of Pop art' gets the retrospective he deserves

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment