Yinka Shonibare MBE makes work from a less entrenched position than his many decorations suggest. This Member of the British Empire (he adopted the initials as part of his name after receiving the honour in 2005) is naturally also a Royal Academician, an Honorary Fellow of Goldsmiths, and has an honorary doctorate from the RCA. Shonibare is one of the most celebrated artists around, a fixture as well received as the ship in a bottle which occupied the Fourth Plinth in 2010 and which now has a permanent home outside the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

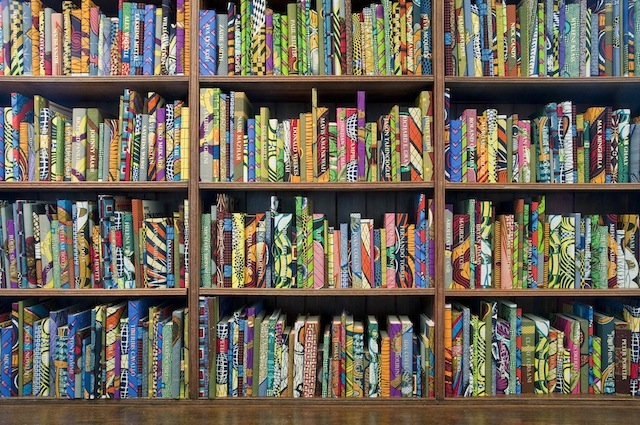

Yet his ambitious new work for year’s Brighton Festival and HOUSE Festival might still surprise. Shonibare has covered 10,000 books with his trademark Dutch/African printed fabric. Look closer, and you will find some 3,000 names on the spines. Most of these are prominent Brits with roots overseas. Some are notorious opponents of immigration. And they all come together in a fine repository of stories, the Old Reference Library in the city’s Museum and Art Gallery.

As nationwide support for UKIP comes to trouble the mainstream political parties, this open-ended piece is timely. And if not exactly biting the hand that feeds, Shonibare is still asking difficult questions.

MARK SHEERIN: What can visitors expect from the new piece. Are there some surprises?

YINKA SHONIBARE: There are lots of surprises in there: Mick Jagger, Jamiroquai, Dido, Helen Mirren. So, it's just about understanding that, actually, this society's very multicultural and the Queen of England came from elsewhere. Her ancestors did. I'm not excluding those who oppose immigration, because as an artist I think my job is to hear both sides of the argument. I can't really take a moral stance as such. You couldn't say immigrants, good, and immigrants, bad [laughs]. It just depends on the situation or on the circumstances of the time. (Pictured below: The British Library [detail], 2014; photo: Nigel Green)

The show is a co-commission between the Brighton Festival and the HOUSE Festival which considers art in domestic spaces. How do you think people use books in the home?

The show is a co-commission between the Brighton Festival and the HOUSE Festival which considers art in domestic spaces. How do you think people use books in the home?

It's a very interesting one because there are people who display books, but don't read at all. It becomes a status symbol. And then I grew up in a household with the old encyclopaedias and lots of National Geographic magazines. The middle classes, particularly the Nigerian middle class, we had books on our shelves as a way of expressing our learned positions. I mean I would describe myself as British-Nigerian middle class. And in those circles it was very important the books you'd display on your shelves.

I've always liked these Trojan-horse ideas, where you can camouflage, but then you can potentially cause a lot of havoc

What do you enjoy reading?

Well, I do read history for a lot of the research, but I also read literature, and I read a bit of fiction. That's because I also belong to an occasional book group. But I also read current affairs a lot. So, it's a combination of current things, historical stuff and a bit of fiction, and some historical fiction like Carson McCullers, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. I'm just about to start the Hunchback of Notre-Dame [laughs]. I reread Gulliver's Travels recently. I re-read things sometimes as an adult just to get a better sense of what I read.

Do you write yourself?

Yeah, a little bit but not in published form. In the beginning I did consider the possibility of doing a bit of writing and I did a bit. But then I also know that for a number of people who've tried to be artists and writers at the same time, their career has been compromised by this, because we don't know whether to think of them as writers or think of them as visual artists. It shouldn't be that way but that's what's happened.

Putting together this show you’ve found yet another use for your hallmark printed fabric. Does the fabric ever come to seem a constraint?

I think constraint is possibly the subject matter. It's almost like, less is plenty; what can you say? It's a language I've established. It's a way of talking to my audience and when they see those patterns they know that's my voice and so it's a rapport which I've developed with them over 20 years. In essence it's no longer just about the fabrics. It's me using that as a vehicle to communicate other things and that's what it's become over the years. So it's form and content. I don't see that as being constraining. It’s actually more of a challenge.

Your work has an emotional range in which anger and playfulness can both be found. How do your projects reflect your mood?

I think like everybody else the artist is definitely reflected in the work, so your state of mind, your emotions, will be reflected. There are times when things are quite dark but then they can be dark and quite humorous simultaneously. So there are points when I'm talking about quite dangerous things, but then I'm also looking at the flipside of those. Visually you can actually collapse a number of ideas simultaneously and this is what I enjoy in work: that tension, that contribution to other things. I like paradox.

You often deal with historical situations. Why do you never comment on contemporary figures?

The problem with history is it's unfolding. So the way we see things now won't be the way we see them in another 50 years’ time and I'm in the midst of all these things. So I prefer to use metaphorical forms or abstract notions to represent ideas, as opposed to specific people or specific events. And with a lot of the things I express, you can identify parallels in history. Because there's a bit of a distance there, it's a poetic way of expressing something which is going on now. But not in a very conclusive manner, because it's not finished yet.

Other projects have shown an interest in the figure of the dandy. What draws you to him?

I was actually thinking about the figure in the Eighties and Nineties when I started work as an artist. Identity issues were something which a lot of artists considered and I was thinking that this figure of the outsider and the dandy is a good metaphor for that, because the dandy is not usually a member of the aristocracy but they gained acceptance to those circles through how they dressed.

. . . like a modern-day hipster?

Kind of, but more political. It's a very silent form of protest because it's about developing your own style, not following the status quo. So it's a very independent position and I think the artist is like that in a way. That's what the artist is always striving for, this independence of mind. I've always liked these Trojan-horse ideas, where you can camouflage, but then you can potentially cause a lot of havoc. (Pictured below: image from Diary of a Victorian Dandy, 1998)

You say you’re a relativist. But do you not think there have been better times than these?

You say you’re a relativist. But do you not think there have been better times than these?

I think that people look at the past with rose-tinted glasses, like, “Oh it was better!” But we're doomed to repeat the same things, really. I mean who knows where this whole thing in Russia is going to go? If you think about the number of conflicts on at the moment, it's almost like we're going backwards. There are lots of mini, local conflicts; it's almost like a lot of small fires all going up. It doesn't necessarily mean I am a nihilist or a pessimist, but it's just observation. I essentially think artists are idealists. Essentially, artists try to see how we could live in the imagination and live beyond the mundane world.

Does the international community of artists form a Utopia?

It would be hard to say that, because every artist does work differently and I don't think there is one way. But of course I come from the Western tradition, so I always think that art should be beyond ideology and this is what I think and so I have no political allegiances. I don't belong to any political party. I don't think that artists can be dragged into such ideologies. Because artists have to avoid bribery by any one group [laughs]. Otherwise you can't do your work properly, if you allow yourself to be drawn into any group. No UKIP, no Labour, no Conservative, no Liberal Democrats, you know. I belong to a political party of art.

- Yinka Shonibare: The British Library at The Old Reference Library, Brighton Museum, from 3 May until 25 May

- Brighton Festival 2014 and HOUSE Festival 2014

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment