Ché Walker claims he wrote Wolf Cub, now in the Hampstead Downstairs studio space, in a two-day blitz prompted by Donald Trump’s election win in 2016. He was working in Atlanta at the time, the home city of Claire Latham, the solo performer for this piece. With Walker directing and the twice Olivier-winning actor Sheila Atim, no less, providing evocative incidental music, they have created a haunting 80-minute monologue that embraces epic events.

The locus of the spasm the US was experiencing when Walker sat down to write Wolf Cub is traced back to Ronald Reagan’s two-term presidency during the 1980s. At this point, Maxine is nine, she recalls, and living with a brutal father who has all the hallmarks of a MAGA hat-wearing good ole boy: anti-immigrant, anti-welfare programmes, anti everything the post-war consensus had created. For him, Reagan — who first used “Let’s make America great again” as a campaign slogan — is the saviour of the nation, until he sees the striking air traffic controllers being cuffed and their union outlawed. But he soon accepts Reagan's punitive stance, reasoning these workers "musta done something against the law and we are a nation of laws”. It’s a punchbag of a statement at which Walker pounds anew.

Even at her young age, Maxine can sense her father’s violence coming, with the instinct of a wild animal. And as she talks, we realise her life is a semi-feral one, motherless, silently hunting deer and rabbits — one of whom has a conversation with her as she tears it apart that sums up Maxine’s emotional landscape: “Whass a family like?” the doe asks her. “Family kinda like what I’m doing to you now.”

Even at her young age, Maxine can sense her father’s violence coming, with the instinct of a wild animal. And as she talks, we realise her life is a semi-feral one, motherless, silently hunting deer and rabbits — one of whom has a conversation with her as she tears it apart that sums up Maxine’s emotional landscape: “Whass a family like?” the doe asks her. “Family kinda like what I’m doing to you now.”

At 12, she knows how to handle her father, but new to her are wilder emotions, which Walker signals by having Maxine describe the features of a wolf she suddenly senses— the claws, the teeth, the fur, the yellow eyes. We realise there is a pure undiluted savagery in her, bereft of any civilising force in her life. Watching a wolf give birth one day, she sees the cub as a sister. Like the wolf, she lives on the margins, scavenging for what she can get. Her dream is to be air, invisible and unaccountable.

She and her father move west to Los Angeles. It’s showtime in US politics: the Iran-Contra affair is about to erupt, crack cocaine use is enslaving the nation’s poorest, and the LAPD will reveal that they are some of the most corrupt cops in the country. We follow Maxine through puberty and beyond, to sexual encounters, a career as a drug dealer, and even to the hellish Contra camps in Nicaragua as she negotiates this urban purgatory to the brink of the abyss. (If the history of this era is unknown to you, the free programme provides a useful timeline of events that put the US on a collision course with rotten Central American regimes.)

But the joy of the piece is that this doomy scenario is played as black comedy. Maxine can deliver a wonderful turn of phrase, sort of like a modern-day Huck Finn; her sentences have a natural rhythm: “School is a lot more fun when you’re packing a gun.” “We know iss all murder and lies from when we first open our eyes.” She’s ribald and funny, sassy in her defiance and brave despite everything.

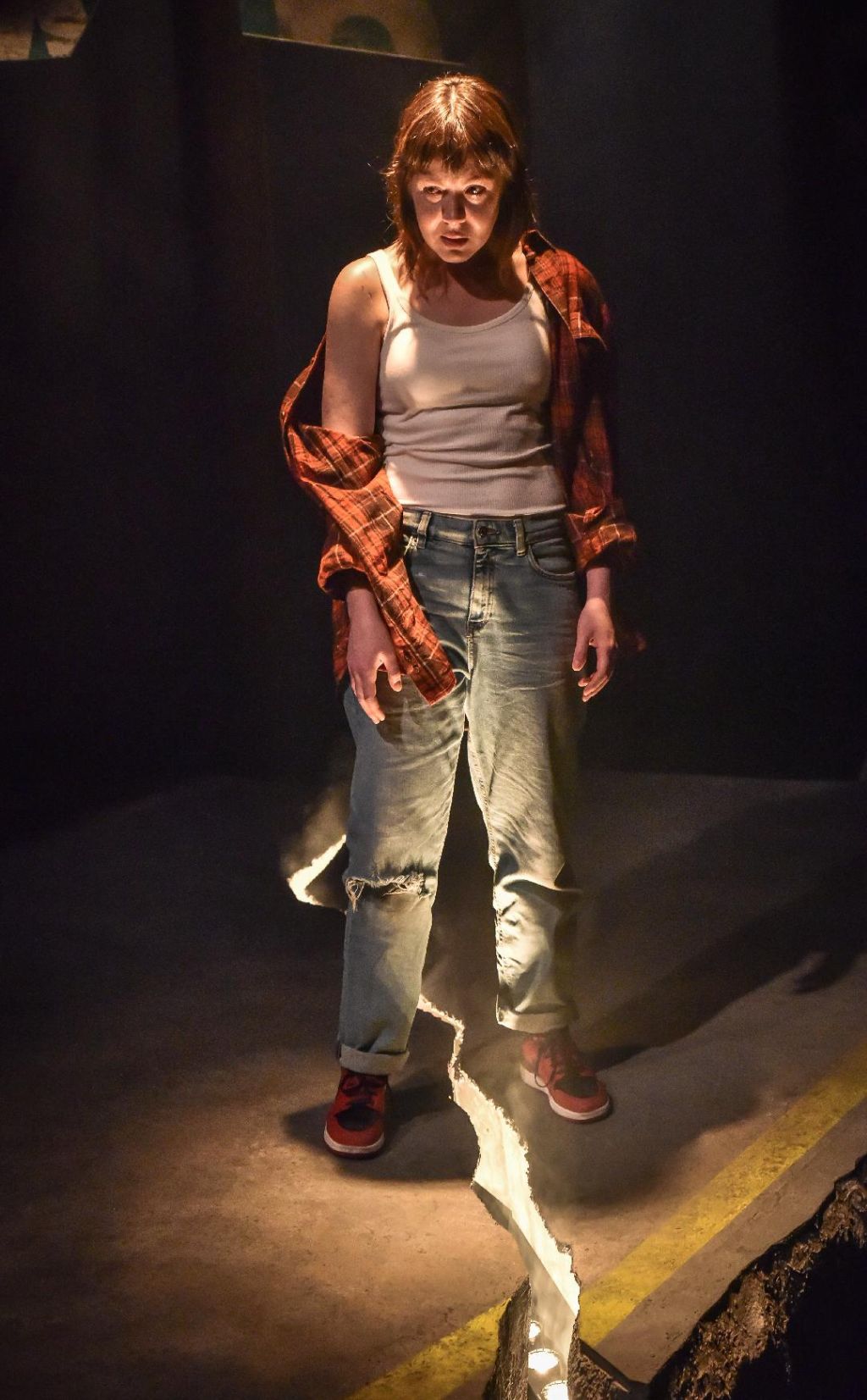

Latham nails the role, beguiling us with Maxine’s humour while never letting us forget she is a feral little hunter. She creeps around in jeans and a plaid shirt, peeping round the side-scenery on a stage with a broken Los Angeles traffic sign as a backdrop and a giant crack ominously running down its middle, at one point summoning down a pair of sneakers hanging on wires overhead (a Breaking Bad tribute? The excellent design is by Amy Jane Cook, lighting by Bethany Gupwell, sound design by John Leonard). Latham’s unadorned face is the ideal canvas for portraying Maxine’s unique kind of innocence, her button-nosed, wholesome features promising an everyday normalcy that life won’t allow her.

Walker skilfully deploys this character as a commentator where others might have chosen a more heroic, politically savvy protagonist to land their jabs. As Reagan infamously liked to say to people accusing him of misdeeds, “There you go again.” The result is a terrific achievement all round.

Add comment